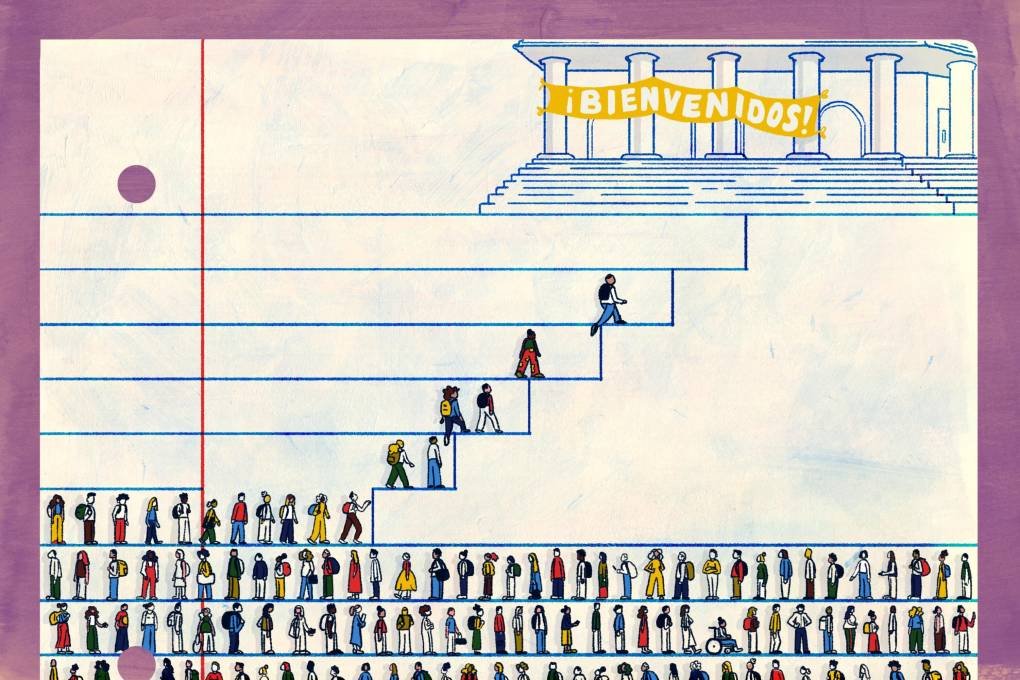

This is because the university has included a group of future customers who are growing: graduates of Spanish high school students like Quintero.

Universities and colleges historically do not do well in the enrollment of Spanish students who are lagging behind their white peers in college attendance. Now their own success can largely depend on it.

“Demography in Bulgaria is changing and higher education has to adapt,” said Glena Temple, President of Dominican.

Or, as Kintero said, smiling, “Now they need us.”

A growing set of potential students

Nearly 1 in 3 students In Class K to 12 is Spanish, the National Center for Education Statistics announces. This is from less than 1 to 4 decade ago. The share of students in public schools, which are Spanish, is even higher in some states, including California, Texas and Florida.

By 2041, the number of graduates of white, black and Asian high schools is expected to fall (by 26 percent respectively, 22 percent and 10 percent), according to the Western Interesting Committee on Higher Education, which monitors this. During the same period the number of high school graduates is expected to grow by 16 percent.

This is done by these young people – often the children or grandchildren of immigrants or immigrants themselves – recently important to colleges and universities.

Still, at a time when higher education needs these students, the proportion of Spanish high schools, directly targeted at college, is more nine than for white students and falls. The number dropped from 70 percent to 58 percent from 2012 to 2022, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Spanish students who enroll in college also drop at higher prices.

In the past, colleges and universities “could hit their (recording) number without engaging this population,” said Deborah Santiago, CEO of Latino Advocacy Organization Excellence in education. “This is no longer the case.”

A possible solution to outline workers’ shortage

A good example of the potential for recruiting Spanish students is in the Cansas City metropolitan area, which includes communities in Missouri and Kansas. The largest school neighborhood in the region, Kansas City, Mexico, is now 58 percent of Spaniard.

Getting at least some of these students enroll in the college “is what we need to prepare as higher education institutions and meet the needs of our communities,” said Greg Mosier, President of Kansas City Kansas Community College, which has started advertising in Spanish newspapers and in Spanish radio.

The response to these changing demographics is about more than colleges that fill places, experts say. This will influence the national economy.

About 43 percent of all jobs will require at least a bachelor’s degree Until 2031, the Center for Education at the University of Georgetown and the workforce assessments. The estimated decline in the number of colleges graduates during this period, the researchers say, can create a serious shortage of workforce.

In this gloomy scenario, helping more Spanish-duty Americans on the way to higher paid jobs seems to be an obvious solution.

However, achieving this goal is a challenge and many teachers are afraid of the Trump administration Attacks against variety programs It can make the recruitment and support of these students even more difficult. Officials from many institutions have contacted it, they did not want to talk about the topic.

Among the other challenges: The average annual household income for Spanish families is More than 25 percent lower than for white families, says the census desk, which means that the college may look inaccessible. Many Spanish students attend public high schools with few college advisers.

And 73 percent of Spanish students are the first in their families who go to collegeMore than for any other group, according to NASPA, Association of Student Affairs Administrators.

These factors can be combined to push Latin American young people straight out of high school in the workforce. From those who go to college, many work at least part -time while studying something examines reduces the probability of graduation.

When Eddie Rivera graduated from high school in North Carolina a decade ago, “The college was not really an option. My advisor was not with me. I just followed what my Spanish culture tells us, which is to go to work.”

Rivera, DACA statusOr deferred actions for the arrival of childhood, they worked at the retirement home, an internal trampoline park and a hospital during a pandemic where his colleagues encouraged him to go to college. With the help of a scholarship program for undocumented students, he ended up in Dominican.

Now, at the age of 28, he is a junior specialty international relations and diplomacy. He plans to receive a master’s degree in foreign policy and national security.

Passing the extra mile to welcome students from Latin American

Small Catholic University, which dates back to 1922, Dominican has a history of education of immigrants children – in earlier times than northern and central European origin.

Today, banners with photos of successful Spanish graduates hang from lamps on the 30 -acre campus, and the Mariachi Group has celebrated Día de Los Muertos.

The tours are conducted in English and Spanish, students are offered on campus, and employees help entire families through health care, housing and financial crises. In the fall, Dominican added a satellite campus largely the Mexican American neighborhood of Pilsen in Chicago, providing two years of associated work -oriented degrees. Every student at the university receives financial assistanceFederal data show.

“I am confronted with an employee or a professor daily who asks me what is happening with my life and how they can support me,” says Aldo Cervantes, a junior business specialty with a minor in accounting he hopes to enter bank or human resources.

There is a Family Academy for parents, grandparents, brothers and sisters and cousins to learn about university resources. As an incentive, families reaching up to five sessions receive a loan for their student to take a summer course without any cost.

“When we look at the Latin population that goes to college, it is not an individual choice,” says Gabe Lara, Vice President for success and engagement for students, using preferences from the University for Latin American descent. “This is a family choice.”

These and other measures have helped more than double the affairs of Spanish students here in the last 10 years, up to nearly 70 percent of 2570 students, according to data provided by the university.

As other universities are beginning to try to hire Spanish students, “they are constantly asking us how we were able to achieve this,” said Temple, President of Dominican. “What they don’t like to hear is that it’s all. You have to commit to it. It has to be more than filling in places.”

Universities and colleges who are seriously involved in enrolling more Spanish students can find them if they want, said Sylvia Hurtado, Professor of Education at UCLA. “You don’t have to look very far.”

But, she added, “you have to support at each stage. We call it that is more responsive than culture, more aware who you are recruiting and what their needs can be.”

Universities are beginning to do this, though slowly. UCLA itself does not start Spanish on its website to accept By 2023Hurtado pointed out – “And here we are in California.”

The new pressure as Dei falls under a fire

Even the smallest efforts to enroll and support Spanish students are complicated by the withdrawal of variety programs and financial assistance for undocumented students.

Florida in February completed a policy For example, to charge lower education at public colleges and universities of uncompanied students. Other countries have imposed or considered such measures.

The Trump administration has transferred a program from the Biden era in support of the Spanish language service institutions. And the US Department of Education, in a letter to colleges, interpreted the Supreme Court’s decision in 2023. Prohibition of “decision -making based on competitionsRegardless of the shape. “

Although the legal basis for this action is widely contested, it has higher education institutions.

Experts say that most programs for recruitment and support of Spanish students would probably not be affected by the anti-de -D campaigns as they are offered to anyone who needs them. “These things work for all students,” says An-Marie Nunes, CEO of the Institute for Diana Student Natalicio for the success of the Spanish student at the University of Texas at El Paso.

But without more than the growing Spanish population, which is enrolled in colleges, these institutions and the workforce face much more challenges, said Nedets and others.

“Getting students to succeed is in the interest of everyone,” she said. “The country will remain behind if not all hands on deck, including those that education has not served in the past.”

In Dominican, Genaro Balkazar is running strategies for enrollment and marketing as Chief Operations Officer. He also has a pragmatic way to look at him.

“We are dealing with the needs of students not for what they are,” Balkan said, “but because they need help.”

This story has been produced by Hachinger’s reportNon -profit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.