January 21, 2025

4 read me

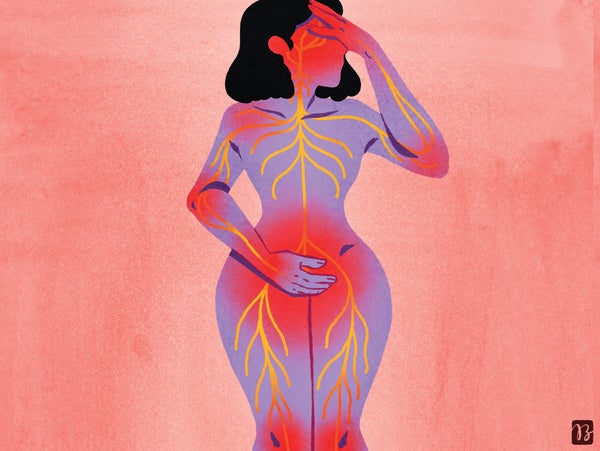

Painful endometriosis can affect the entire body, not just the pelvis

This disease is now genetically linked to inflammation, asthma, migraines and more

The pain of endometriosis, which affects one in 10 American women born to women, can be excruciating. Some people cannot work or go to school. However, many doctors do not recognize the symptoms. On average, it takes sufferers seven to nine years to get a diagnosis.

This shocking statistic, along with the lack of awareness of endometriosis, is a powerful example of the knowledge gap regarding women’s and men’s health. has been limited funding and research what causes or is most at risk of endometriosis. That is finally changing, in part because the understanding of endometriosis is changing. It is not a purely gynecological condition. “In the last three to five years this disorder has been reframed as a neuroinflammatory disease of the whole body,” says reproductive biologist Philippa Saunders of the University of Edinburgh. “It’s not just a bit of tissue stuck in the wrong place. Your whole body has reacted.’

Endometriosis, which involves the tissue of the uterus, begins with a process called retrograde menstruation, in which menstrual blood flows up the fallopian tubes and into the pelvis. The blood carries away pieces of endometrial tissue, which lines the uterus. Sometimes, instead of being cleared by the immune system, this tissue attaches to the ovaries or pelvic lining, then grows and creates its own blood supply. Lesions can cause infertility as well as debilitating pain. “We’re not talking a little pain here,” Saunders says. “(People) can’t function.” And unlike menstrual cramps that occur during one period, endometriosis pain can flare up at any time.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

The medical profession’s habit of reducing health problems to narrow silos—traditionally, only gynecologists saw endometriosis patients—hasn’t helped. “We divide human health into specialties and systems, but now we know that (those systems) are much more interconnected than we thought,” says Stacey Missmer, a reproductive biologist at Michigan State University. Endometriosis causes symptoms and effects that affect many other parts of the body, she noted.

For example, adolescents and young women with endometriosis are five times more likely to be diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome than women without endometriosis. Cardiovascular events are rare in all women under 60, but in those with endometriosis, the relative risk of high blood pressure, stroke, angina, or heart attack increases by 20 to 80 percent, depending on the test and the condition. Patients are twice as likely to develop rheumatoid arthritis, and asthma, lupus, and osteoarthritis are more prevalent among people with endometriosis. These people are also more likely to suffer from overlapping conditions, such as migraines, back pain, and fibromyalgia, a chronic pain condition.

Scientists still can’t say for sure why so many of these conditions are seen together. “We think one of the key pathways is chronic inflammation,” says Missmer. It could be, for example, that affected individuals have inflammatory responses to triggers shared by some diseases.

Researchers know that half of the risk of endometriosis comes from genetic factors. Although earlier studies did not find a common gene with a high risk of the disease, similar to this BRCA breast cancer gene—more recent large-scale work has implicated genetic variation across the genome. Examination in 2023 Nature Genetics About 60,000 people with endometriosis and more than 700,000 people without the disease found more than 40 places in the genome that harbor changes associated with an increased risk of the disease. “This really led to a leap in our understanding,” says genetic epidemiologist Krina Zondervan of the University of Oxford.

In the same study, the researchers highlighted the shared biology of some of the diseases that co-occur with endometriosis. For example, they found a link in the genetics underlying endometriosis and other types of pain, such as migraines. Such pain conditions trigger a biological process called central sensitization, which occurs when chronic pain changes the way the central nervous system reacts to pain stimuli, and many of the genes involved are related to the perception or maintenance of pain. They have also found links to inflammatory conditions such as asthma.

What can help with diagnosis and treatment is the recognition that endometriosis is not a single disease. It is a condition with three subtypes. Ovarian endometriosis, which causes lesions on the ovaries, is the most hereditary. Deep endometriosis extends further into the pelvis and produces very hard nodules. In peritoneal or superficial endometriosis, smaller lesions are more widely dispersed throughout the pelvic lining. As with breast cancer, subtypes are likely to have different risk factors.

Until recently, the only way to diagnose endometriosis was laparoscopic surgery. But now less invasive methods are being used. Ultrasound imaging can detect ovarian endometriosis, for example, and MRI scanning can reveal deep-seated lesions. Unfortunately, imaging still doesn’t work well with peritoneal endometriosis, which is the most common type. Furthermore, patients should be directed to these images, and not all of them are due to misdiagnosis and disparities in access to health care.

For treatment, surgical removal of the lesions works for some patients, but not all. Identifying upcoming conditions can determine who will be helped. Those who experience widespread pain beyond the pelvis may not benefit from surgery. “There’s nothing to cut,” says Missmer. Clinical trials are underway in the UK to look at outcomes with and without surgery.

Anyone with an endometriosis diagnosis or worrisome symptoms right now should discuss this not only with their gynecologist, but also with their primary care physician. This is not a body part problem.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily their own. American scientific