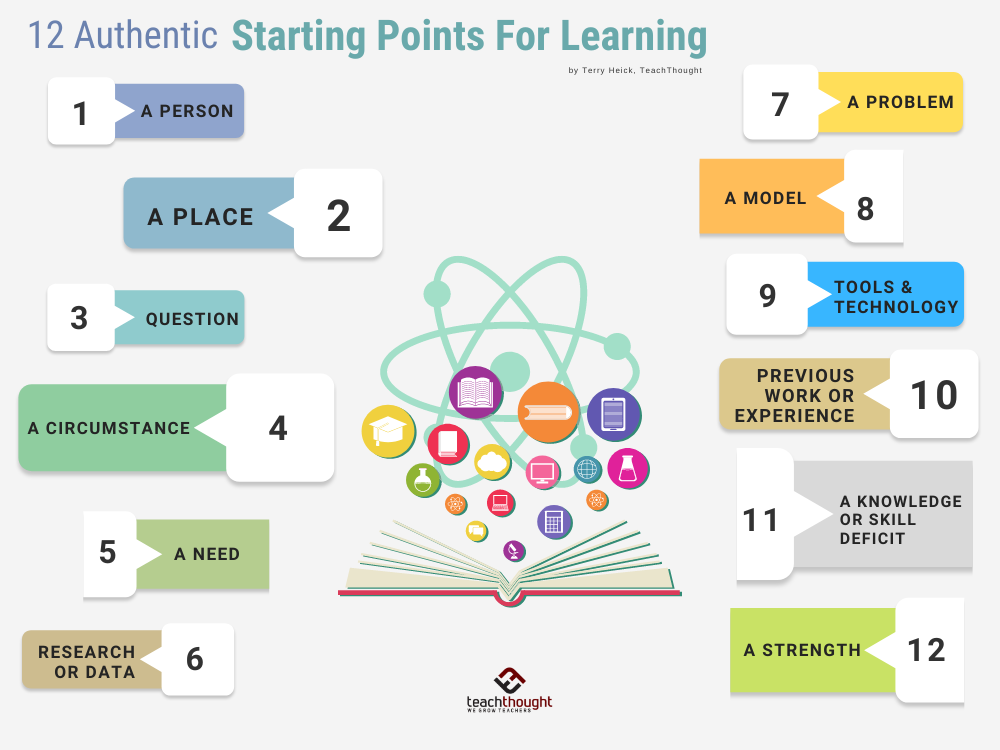

Learning – real, informal, authentic and lifelong learning – can ‘start’ with almost anything.

Thus, this is clearly not an exhaustive list. Nor am I implying that these are the “best” starting points or that they would in any case be effective in your classroom. There are simply too many variables.

What I hope to achieve with this post is to help you start thinking about what ’causes’ learning – and more specifically where and how it happens.

What causes learning?

In the real world, learning never stops, but it’s not always clear that it’s happening.

Or at least we think about it differently than classroom learning. Consider an observation or event—a young child watching older children play a sport, for example. This modeling of physical behavior by older children serves as both motivation (why) and information (how) to promote learning in the younger child.

Similarly, anything from an “event” (touching a hot stove) to a conversation to reflecting on something that recently happened can act as a “jumping point” for learning. Metaphorically and literally, failure is a wonderful starting point for learning, properly placed in the mind of the person who is “failing.”

At the level of detailed lesson and activity, the starting point is usually an academic standard that is used to form a lesson objective sometimes called a learning goal or objective. Taken together, all of these conditions work as intended learning outcomes.

See also What is a thematic unit?

There is still considerable flexibility in the above, teacher-led, top-down approach. Such an approach can still be student-centered, differentiated, open-ended, and guided (in part) by student inquiry. However, bottom-up learning approaches such as self-directed learning, inquiry-based learning, personalized learning, and (done well) project-based learning all offer new possibilities—new “starting points” for the learning process itself.

And with the new starting points come new roles for all the “parts” of the learning process, including teachers, students, questions, assessment, feedback on learning, purpose and audience, assessment, quality standards, and more. For example, learning often “begins” with an activity created by a teacher based on a learning standard (itself embedded in an intentional sequence). At first, the student’s role is passive as he receives guidance and tries to make sense of the given task or activity.

Depending on the design of the lesson, they may or may not become more active and engaged in the learning process, but even if this happens, they are often “committed” to doing the task or activity “well” – that is, they are, at best, trying to do a “good job” according to the conditions and quality criteria suggested by the task (usually created by the teacher).

If, instead, the learning process began with an authentic problem that the student genuinely wanted to solve but did not have the knowledge or skills to do so, it is immediately clear how everything changes from the roles of the teacher and the student to the design of the activity, the knowledge requirements, the sequence of procedures, etc. Note that not all of the alternatives to traditional lesson planning below are feasible in every classroom or for every “lesson” or “lesson.” We hope to give you some ideas to start thinking for yourself about how you plan lessons and modules and how the design embedded in them matters – how much even a simple starting point can affect everything.

Also, the potential really unfolds when you consider the shape of how you plan, in addition to the starting point of the learning process itself. For example, each of the starting points below can be used in a traditional lesson planning model. It is not necessary to use inquiry-oriented learning in a project-based learning model to promote personalized learning in an open, student-centered model. A question starting point, for example, can be used in an early-lesson brainstorming session that helps students shape their understanding of a concept—immigration factors, economic models, understanding cognitive biases, etc.

Note that just because learning starts with a person, place, or question doesn’t mean it can’t be used to promote mastery of academic content in the same way that project-based learning can lead to improved academic outcomes (not just “cool projects”).

1. With a person

This could be a student – their personal need, for example. Something from home or the classroom. It can also be an academic need – a knowledge or skill deficit or an opportunity to improve an existing gift or talent. But learning that begins with a person need not be the student at all. It could be their friends or family. It can also be a historical person, a person of interest today, etc.

Learning that begins with a person—a specific person with specific knowledge requirements and attachments, needs and capabilities—is inherently human, learner-centered, and authentic.

2. With space

Everywhere is a place.

And from placeI don’t mean a big city or a famous landmark. The places I mean they are smaller – less about geography or topography and more about meaning and scale. It could be a litter creek that needs cleaning, or a planned and planted garden.

Or it might be more metaphorical place– still a physical place, but one whose meaning depends on an experience or event – a place where husband and wife met or where a baby took its first steps. Or it can be bigger – a family home or community with unique needs, opportunities, attachments, histories, legacies and past, present and future.

See also What is the technique of forming a question?

3. With a question

They can be academic or authentic, based on knowledge or wisdom (according to age), possibly open or closed can be effective at times (cf. Types of critical thinking questions), created by teacher or student, important or trivial, etc.

4. With circumstance (historical, present, future possibility, etc.)

Any real or fictional circumstance or scenario can provide an authentic starting point for learning. Examples? Climate change, population growth, the spread of propaganda, and war are all possibilities. It doesn’t have to be “negative” either. A circumstance could simply be a family with a new baby or a student who has just received his driver’s license and therefore needs new knowledge and skills.

5. In need of a family or community

This overlaps a lot with person and place, but gives you the opportunity to really focus on family and/or community – to become more granular in your brainstorming and lesson planning, taking into account the unique nature of particular families and communities and how learning can support them and how they can support and nurture a child’s learning.

6. With research (its citations, conclusions, premises, methodology, etc.)

Research is a wonderful starting point for learning, if for no other reason than as a product or body of knowledge, it was initiated by a need to know or understand. A reason to study something in a formal way with formal methodologies and unique premises and conclusions.

7. With a problem

This is the idea behind challenge-based learning, which often takes the form of project-based learning.

See also What are the types of project-based learning?

8. With a model

Any kind something can function as a model. A book, a building, a river, a person, a movie, a game, an idea or a concept are all things with characteristics that can be studied and learned from them – “stolen” in the sense that you can take ideas, lessons, characteristics, etc. from here and apply them there. I wrote a bit more about this in The definition of blended learning.

To be clear, I don’t mean anything close to plagiarism. In the same way that so many modern hero stories borrow – consciously or not – from Homer’s Odyssey or the Epic of Gilgamesh, a building or a rural landscape can be studied and used as inspiration for understanding, knowing and doing.

Birds were studied for their method of flying and eventually airplanes were invented. There have been many bad video games that had an interesting aspect – a character or a game mechanic, for example – and often these “wins” were carried over as lessons and used “better” in future video games. The idea of pixels inspired Minecraft and so many Minecraft-like games.

Concepts like the water cycle or the food chain or our system of classifying animals contain ideas that are clearly effective and so make great starting points for learning.

9. With technology

This one is similar to number 8 but is more focused on specific technologies – solar panels or computer microchips or iPads or power plants can be used as research models. In this way, students learn from the genius in everyone.

10. With previous work, projects, writing, ideas, etc.

The student can review past projects, writing, activities, etc. and to use them – whether they were poor or sterling – as learning opportunities. Restart, revise, refine, redesign and improve.

11. With a specific skill or knowledge deficit

If a student has a specific skill or knowledge deficit – something they need to know or can do – this makes a very obvious and practical starting point for the learning process and is one of the most commonly used in education. It is also a catalyst for a lot of informal learning. If a child wants to be able to ride a bike or hit a baseball, each begins with a skill deficit and is overcome by creating new knowledge (knowledge acquisition) and practice (skill acquisition).

See also Correcting the critical thinking deficit

12. With a specific skill or knowledge, power or talent

Like number 11, the learning process here begins with a particular student, but instead of correcting deficiencies, a strength, talent, or “gift” is used. This can/often will result in an enhancement of that power, but may also require applying or transferring that power. This could be a student who can sing, using this gift to create art/music, serve a community (eg sing to the elderly in a nursing home) or make new friends.

12 ways to start the learning process 12 places to start your planning 12 alternatives to start planning with a standard 12 starting points for ensuring authentic learning