Business -Reporter

Gonzalo Rojas

Gonzalo RojasThe proposed law in the Colombian Congress seeks to prohibit the sale of goods that Pablo Escobar’s former Lord Drug Lord. But the opinions are divided into this.

On Monday, November 27, 1989, Gonzalo Rohas attended a school in the Colombian capital Bogot when the teacher pulled him out of the class to deliver some devastating news.

His father, who was still named Gonzalo, died in a plane crash that morning.

“I remember leaving and saw my mother and grandmother waited for me,” says Mr. Rohas, who was only 10 years old at the time. “It was a very, very sad day.”

A few minutes after taking off, an explosion aboard Avianca 203 killed 107 passengers and crew, as well as three people on the ground affected by the garbage fall.

The blast was no accident. It was Pablo Escobar’s focused bombing and his Medellín cartel.

While the era, determined by narcotic wars, explosions, abductions and high -murder, was largely attributed to the past Colombia, the escabar’s heritage is not.

The notorious criminal who was killed by security forces in 1993 has reached an almost iconic status worldwide, immortalized in books, musical and television productions such as Narcos Netflix series.

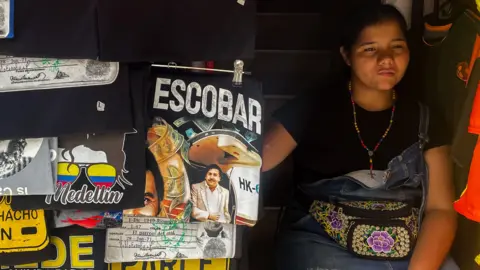

In Colombia, his name and face are decorated with mugs, brands and T -shirts in tourist shops that serve mostly curious visitors.

But the proposed law in the Colombian Congress seeks to change this.

The bill wants to ban the escabore goods – and in other convicted criminals – to help put an end to the glorification of drugs, which was held mainly in the world trade in cocaine and widely attracted to at least 4,000 murders.

“The difficult problems that are included in the history and memory of our country cannot simply remember the T-shirt, or the sticker sold on the street,” says Juan Sebastian Gomez, a member of the congress and co-author of the bill.

The proposed law prohibits selling, as well as the use and wearing of clothing and items that promote criminals, including escabar. This will mean fines for those who have violated the rules and the temporary suspension of the business.

Catherine Ellis

Catherine EllisMany suppliers who sell the goods claim that the law prohibiting this product hurt their means of existence.

“It’s scary. We are entitled to work, and these Pablo T-shirts are especially selling well,” says Joann Montai, who owns an Escobar counter in Comuna 13, a popular Medeline tourist zone.

Medeline, hometown of Escabar, was known as the “most dangerous city in the world” in the late 80’s and early 90’s with a violence associated with narcotic wars and armed conflict in Colombia.

Today it was lively at the Innovation and Tourism Center, and suppliers are trying to earn visitors who want to pick up home souvenirs – some escabar.

“This Escobar product benefits many families – it supports us. It helps to pay rent, buy food, care for our children,” says Ms. Montai, who supports herself and her young daughter.

Ms. Montoy says that at least 15% of her sales come from Escobar products, but some sellers say BBC, which is up to 60%.

Catherine Ellis

Catherine EllisWhen the bill is approved, the sellers will be determined to get acquainted with the new rules and stop its Escobar shares.

“We will need a transitional stage so that people can stop selling these products and replace them with others,” explains Congressman Gomez. He says that Colombia has more interesting things to show what addicts, and that the Association with the Escabar stigmatized the country abroad.

Some T -shirts, which are sold about £ 5, carry an escurabar phrase – “silver or lead?”. This symbolizes the choice that the Cartel’s chief gave to those who threatened their criminal operations: to take a bribe or to die.

Mary Suarez’s shop assistant believes the profit earned from Escobar goods is not ethical.

“We need this ban. It did horrible things, and these souvenirs are things that should not exist,” she says, explaining that she was unpleasant that her boss is escabar.

It was believed that the Escobar and his Medellín cartel were in one point controlled by 80% cocaine, which was part of the United States. In 1987, it was named one of the richest people in the world magazine forbes.

He spent some of his happiness, developing in devoid of quarters, but many consider it a tactic to acquire loyalty in some segments of the population.

During his father’s death, Mr. Rohas remembers him for a calm and responsible person who loved his family. For his bill, it is a defining moment.

“This is a milestone on the way on how we reflect on what is happening in terms of Pablo Escabar’s commercialization to fix it,” says Mr. Rohas.

However, he has criticism about the proposals. He believes that the bill does not focus on education.

Juan Sebastian Gomez

Juan Sebastian GomezMr. Rohas recalls the day many years ago when he met a man who wears a green T-shirt with an escobar silhouette, and the words “Pablo, president”.

“It caused me such confusion that I couldn’t say anything about it,” he says.

“We need to be more emphasis on how we deliver different messages to new generations, so there is no positive image of what the cartel is.”

Mr. Rohas actively participated in the efforts to rearrange the stories around the escabore and the drug trafficking. Together with some other victims, he launched Narcostore.com in 2019, an online store that seems to be selling Escobar subjects.

But none of the products actually exist, and when customers choose an item, they are shown a video testimony from the victim. Mr. Rohas says the site has collected 180 million visits from around the world.

In the Colombian Congress, the bill faces four stages that it must pass before it can become a law. Gomez says he hopes that it causes reflections both inside the Congress and outside.

“In Germany, you do not sell Hitler or Swastikas T -shirts. In Italy, you do not sell Mussolini stickers and you don’t go to Chile and get a copy of Pinochet’s personality certificate.

“I think the most important thing that the bill can do is create a conversation as a country – a conversation that has not happened yet.”

Medelina Mayor – who was also a presidential candidate in the 2022 election – publicly supported the bill, calling the goods “insulting for the city, country and victims”.

In El -Blood, a supermarket, popular with tourists, three Americans view a stall that is filled with souvenirs. One buys a hat with the name of an escobar and a face printed on the front. He says he wants the memory of “story”.

But for the supporters of the bill, it is not about removing the escabore from history, it is about erasing the mythical design, contributing to the new way to honor the victims he killed – and to recognize the protracted pain of the victims left behind.