January 14, 2025

4 read me

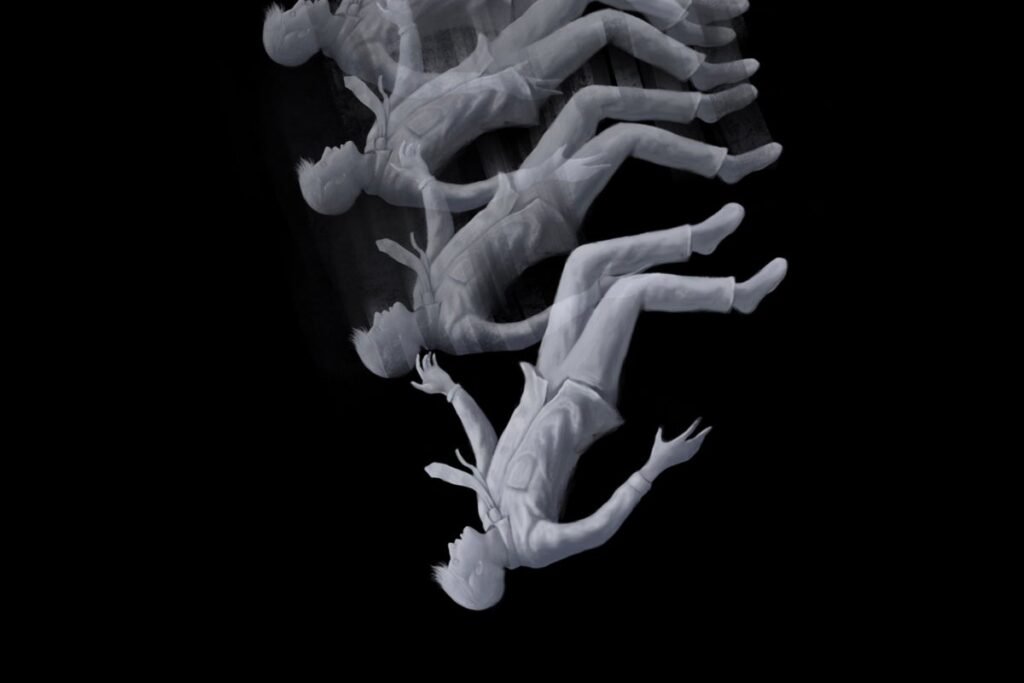

Why are recurring dreams usually bad?

Recurring dreams can be about taking a test that the dreamer has not studied for, having to give a speech, or being attacked. Here’s why our brains come back to those unpleasant dreams again and again when we’re asleep

Jorm Sangsorn/Getty Images

Why does it look the same? dreams follow us? Maybe you’ve dreamed of flying like a bird since childhood, or you’ve recently started revisiting a certain place or time while you sleep. Maybe a bad day at work still gives you exam nightmares, even if you haven’t been a student in decades.

Well, you’re far from alone. Recurring dreams are a surprisingly common phenomenon: research shows this up to 75 percent adults experience at least one in their lifetime. These dreams are on a spectrum: sometimes they are almost the same every time they occur, but they can also have different themes, locations, or characters set against different backgrounds. This in spite of what distinguishes recurring dreams from nightmares caused by post-traumatic stress disorder, is the psychological state of people. relive specific memories while sleeping with much less variation from their waking life. Experts still don’t know why we have recurring dreams, but new research is helping to better identify patterns in their frequency and content, as well as the scenarios that trigger them.

Recent research has reinforced the long-held idea that recurring dreams are often—but not always—bad. in one 2022 survey according to Michael SchredlThe head of the sleep laboratory at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Germany and his colleagues found that adults marked recurring dreams as “negative tones” two-thirds of the time; these dreams often touched on issues such as being chased or attacked, being late or failing at something. Participants’ positive recurring dreams, on the other hand, involved themes such as flying or finding a new room in their home.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

The reasons why we might be more prone to negative dreams are not fully understood, but Schredl says that dreams usually do. over dramatize something in our waking life—we feel powerless to change even a small feeling or situation. “In the dream, it becomes much more emotional, although the connection is not always direct or obvious,” he explains.

Psychology and neuroscience offer additional clues. For example, we have the trend of what is known as negativity bias: tendency to fixate more on unpleasant thoughts, emotions or social interactions than on positive ones. This behavior is based on our subconscious mind to solve negative situations that threaten our survival. Negativity bias can be exacerbated during sleep because it is our dream brain moisturizes the area it activates the parts associated with linear logic and emotion, weakening the filter between our thoughts and feelings.

Understanding the psychological basis of recurring dreams has been difficult because they are difficult to study control dreams in the experimental context. But events such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks or the COVID pandemic, which many people experience shared trauma, have allowed scientists to investigate certain patterns associated with dreams in more detail.

People who experience regional or global disasters often have a “striking” increase in recurring negative-toned dreams afterward, he says. Deirdre Leigh Barrettdream researcher and author of the book 2020 Pandemic dreams. During the pandemic, Barrett collected more than 15,000 dream reports and in twin publications—a book chapter and a to analyze– It showed that recurring themes of fear, illness and death were two to three times more common in people’s dreams than before the pandemic. Common accounts include seeing loved ones die, seeing swarms of insects (perhaps derived from the description of COVID as a “bug,” Barrett says), and experiencing disasters such as tidal waves that are emblematic of something all-consuming.

Barrett found that early in the pandemic, dreams tended to be more literal and caused more fear and anxiety. Over time, they moved on to less frightening but still unpleasant situations associated with social embarrassment, such as being the only person in public not wearing a mask. “It’s obviously somewhat related to what’s going on in our daily lives,” Barrett says, “referring to what’s called.”continuity hypothesis“. “If you don’t process emotions during the day, your nighttime consciousness will try to process them at night,” she explains.

Barrett and other experts emphasize that recurring negative dreams are common and normal and that there are steps to control them. Some people have succeeded in a practice called imagery rehearsal therapyin which repeatedly imagine their nightmares with happy endings before going to sleep Nirit Soffer-DudekThe mindfulness researcher and clinical psychologist at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel also recommends practicing good “sleep hygiene.” By establishing a consistent sleep schedule, limit screen usage and avoiding caffeine or alcohol before bed, “you’re less likely to fall asleep when you’re in a high emotional state,” he says. “The best advice I can give is to try to set strong boundaries between waking and sleeping so you don’t bring anxiety into your dreams.”