The construction of a new basketball arena threatens to flood the neighborhood with traffic and raise rents.

Friendship Gateway Chinatown in Philadelphia.

(Pat Greenhouse/Getty)

Debbie Way, who grew up in Upper Darby, a white working-class community on the outskirts of Philadelphia, remembers going to Philadelphia’s Chinatown every week with her parents to get groceries. For Wei, whose parents were both Chinese immigrants, Chinatown was the place in the city where she felt most comfortable.

At 150 years old, Chinatown is one of the oldest sustainable communities in Philadelphia. Created by Chinese immigrants fleeing racial violence on the West Coast, it was once considered an undesirable downtown neighborhood. “Even as a child, Chinatown was a red light district,” Wei recalled. “There were a lot of bars that you would call ‘run down’ – not a place for people and families.”

Wei has spent the past two years organizing a citywide and cross-racial campaign against the construction of a new arena for the city’s Philadelphia 76ers basketball team, which threatens to fill the neighborhood with more traffic and raise rents, according to the Coalition to Save Chinatown. On December 12, the city executive committee will start voting for approval or rejection of the construction of the arena.

Developments targeting Chinatown date back to the 1920s, when the Bell Telephone Company purchased and demolished a block of Race Street, displacing Chinatown residents. Throughout the mid-20th century, city officials used the “great area” to displace residents and create new developments, from Broad Ridge and the Vine Street extension to urban renewal projects that turned large parts of the area into industrial areas. centers and parking lots.

However, Chinatown survived and grew when the immigration laws were repealed. Threats to the neighborhood’s existence intensified in the 1960s and ’70s, including a project to widen Vine Street into an expressway that threatened an important educational and religious institution. Chinatown residents organized, pushing the city council to accept a smaller highway project. Another setback occurred in 1991 with the construction of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, which displaced 200 Chinese residents and seven Chinese businesses.

“It’s like Jenga, if you pick up enough bricks, the thing will fall,” Wei said. “By the time the convention center went in, I think the community realized we couldn’t afford another major development like this. We are at the maximum of what the community could take.” Wei says that’s when Chinatown started to get more organized — and win. In 1993, the community rejected a proposal to build a federal prison. In 2000, the people of Chinatown won again, stopping construction of the Phillies’ new baseball stadium. In 2008, the organizers stopped the proposed casino.

Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker has openly supported the arena development, as has much of the City Council. But Vivian Chang, executive director of Asian American United, is optimistic that Chinatown can win again. “In all these fights — the stadium, the casino — every time the mayor wanted it, the city council wanted it, but we still won.” But this time, Chung said, the fray involved even more deception by city leaders who failed to do adequate public outreach, overstated the economic benefits the Sixers’ arena could bring to Philadelphia, and imposed a shoddy concession agreement for society.

As a former resident of Washington, D.C., Chang has seen the damage an arena can do to Chinatown. Ever since Capital One Arena arrived in the neighborhood, Chang says D.C.’s Chinatown has not been able to recover from the gentrification and displacement it caused, and that the economic benefits of the stadium are unlikely to ever outweigh the harm.

Philadelphia city leaders and the arena’s developers say the new arena will bring a significant increase in foot traffic to the city’s commercial corridor, along with plenty of new tax dollars. Chang disagrees: “A lot of their numbers are really inflated. Every sports team does the same management (commissioning) study from a paid consulting group to say all this activity is going to come in and all these taxes are going to come in, but they don’t materialize. If we look at these so-called studies in different cities and stadiums, they are usually overestimated by 80 percent.”

Roger Null, professor emeritus of economics at Stanford University, is also skeptical of the developers’ claims that the arena could boost the local economy. “Sports teams are not particularly big business,” Nall said. “The revenue an NBA team gets from the arena they play in is about the same as two or three Macy’s stores.”

For Null, what makes sports teams unique is that their social value exceeds their economic impact—a phenomenon that makes arena development so popular. “Stadiums are a lot more expensive than a business the size of a sports team,” Nall said. “Sports facilities became monuments to the owners and the local politicians who helped subsidize them, the mayors who cut the ribbon on the construction site.” What’s more, Null points out, multiple impact studies have shown that sports arenas can even slightly hurt a city’s sales tax collection. And since they’re mostly closed year-round, opening only for games and other events, they function more as “economic black holes.”

Chang points out that the area’s small businesses will be hit hard by the development, as Chinatown will be cut off from its regular customer base during construction for at least six years. “A lot of businesses are still on the sidelines because of Covid and anti-Asian violence,” Chang said. “They can’t afford to lose all that income.”

popular

“Swipe to the bottom left to see more authors”Swipe →

Vivian Truong, a professor at Swarthmore College in suburban Philadelphia who studies the history of Chinatowns, believes that there is a lack of credibility in Philadelphia’s Chinatown because of past broken promises by developers and a tendency to see Chinatown as an obstacle to progress instead of a place for growth.

“There is a denial of the fact that Chinatown is not just a place stuck in time and history,” Chiong said. “But this is a living, ongoing district, not a relic of the past. Not surprisingly, a lot of this history of Chinatown in Philadelphia, which is the target of these development projects, essentially sees it as this area that can be a blank slate for the city to build whatever it wants.”

According to Wei, the arena proposal involved an out-of-district organization. David Adelman, founder of Campus Apartments, is one of the main developers of the arena and is credited with helping to move the black community in West Philly. David Blitzer, co-owner of the Philadelphia 76ers, is a top executive at Blackstone, which the United Nations has blamed for the global housing crisis. Neither the arena’s development team nor City Hall responded to a request for comment.

“We knew we couldn’t win just by organizing Chinatown,” Wei said. “We saw a connection between these billionaire developers and what was happening in communities across Philadelphia in terms of housing prices and sprawl, so we formed the citywide Save Chinatown Coalition.”

According to Clarise McCants, it was the shared experience of gentrification and displacement that strengthened the citywide coalition against the arena development. McCants is a member of Black Philly 4 Chinatown, which was founded in late September after Mayor Parker officially endorsed the arena. “She talked about a time when black people could shop on Market East, talking subtly to Asian businesses, ‘other people’s businesses,’ that were in black neighborhoods,” McCants said. “We just thought, wow, that’s some pretty dangerous rhetoric that seems to be trying to pit black people against Asians in this fight, given that the fight against the arena was largely driven by organizers in Chinatown. But the reality is that the majority of people in the city are against the arena, and I think that’s true among black people as well.”

McCants says jobs in the arena will be low-paying and mostly temporary, trapping black workers in a cycle of poverty. “Aramark workers went on strike this year because they weren’t being paid a living wage at the arenas in the stadiums that South Philly already has,” McCants said. “What makes us think that these new jobs that are going to be at the Sixers arena are somehow going to be better?”

As part of its organization, Black Philly 4 Chinatown, sent an open letter to City Hall in late November explaining how the proposal would further harm black working-class communities. “There’s been a history of this kind of solidarity between the black and Asian communities, and we knew we wanted to live up to the legacy of that history of solidarity and continue that for the opportunity to stop this arena,” McCants said. . “But also for a longer struggle against the fact that profits are placed above the real needs of the people.”

According to Chang, the city’s approval will not be the end of Chinatown’s struggle. “The city council can vote for it, but we can sue them, tie them up in the courts,” Chang said. “We’re going to be fighting this for years to come.”

More from Nation

December 10th is Human Rights Day, the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), one of the world’s most groundbreaking global pledges.

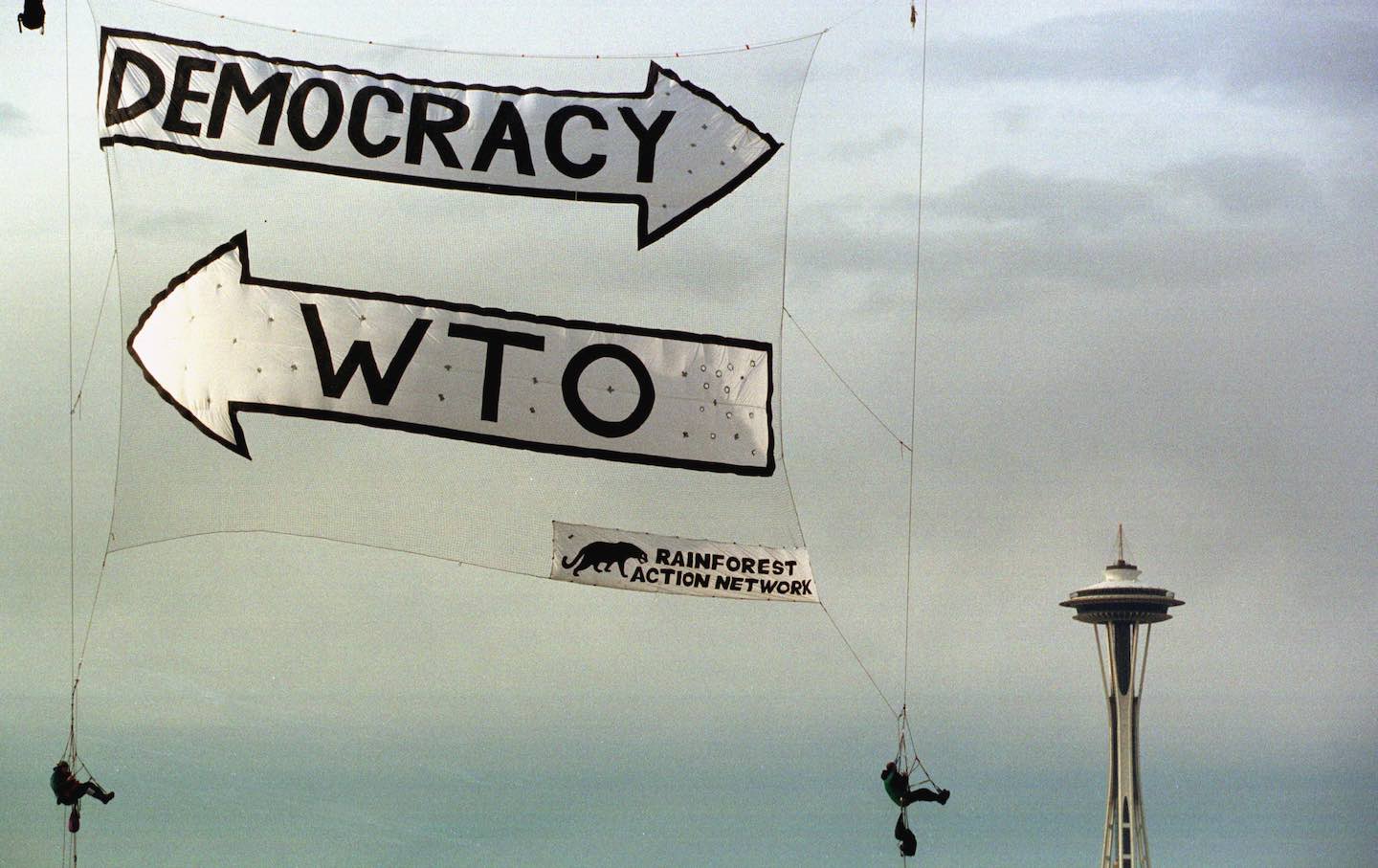

Protests against the WTO Conference in 1999. were short-lived. But their legacy has been reflected in American political life ever since.

Amin El Gamal, head of SAG-AFTRA’s Middle East and North Africa membership committee, has advocated for a statement in support of the Gaza ceasefire – so far without success

Patria, Minerva and María Teresa Mirabal were sisters from the Dominican Republic who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo; they were killed on November 25, 1960. and…