“There are many schools that are effective at helping students learn, even in high-poverty communities,” said Shawn Riordan, a Stanford sociologist who was part of the team that developed the Stanford Education Data Archive. “The TNTP report uses our data to identify some of these and then digs deeper to understand what makes them particularly effective. That’s exactly what we were hoping people would do with the data.”

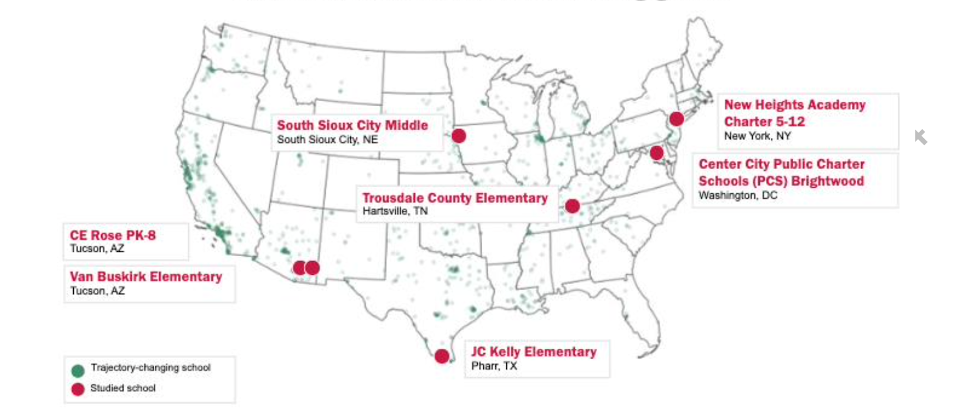

TNTP did identify seven of the 1,345 high-performing schools it selected for in-depth study. Only one of the seven schools had a majority black population, reflecting the fact that black students are underrepresented in the best performing schools.

The seven schools range widely. Some were big. Some were small. Some were urban schools with many Hispanics. Others were predominantly white, rural schools. They used different teaching materials and did many things differently, but TNTP highlighted three traits that it believed these schools had in common.

Seven out of 1,345 schools where students started behind but made great progress in learning over the decade from 2009 to 2018.

“What we found was not a perfect solution, a perfect curriculum, or a rock star principal,” the report said. “Instead, these schools share a commitment to doing three main things well: they create a culture of belonging, provide consistent instruction at the grade level, and build a coherent curriculum.”

According to TNTP’s classroom observations, students received good or strong instruction in nine out of 10 classrooms. “Across all classrooms, a consistent build-up of good lessons—not unachievably perfect—distinguishes trajectory-changing schools,” the report said, contrasting that consistent level of “good” with your earlier observation that most American schools have good teaching, but there is a lot of variation from one classroom to another.

In addition to good instruction, TNTP said students at these seven schools are receiving grade-level content in their English and math classes, although most students are falling behind. The teachers in each school used the same common curriculum. According to TNTP’s report, only about a third of elementary school teachers nationwide say they “predominantly use” the curriculum adopted by their school. At Trousdale County Elementary in Tennessee, one of the model schools, 80 percent of teachers said they do.

While many education advocates insist on adopting a better curriculum as a lever for school improvement“It is possible to get trajectory-changing results without a perfect curriculum,” TNTP wrote in its report.

Teachers also had regular, scheduled sessions to collaborate, discuss their instruction, and note what worked and what didn’t. “Everyone has the same high expectations and works together to improve,” the report said.

Schools also gave students extra instruction to fill in knowledge gaps and extra practice to solidify their skills. These extra support classes, called “intervention blocks,” are now commonplace in many low-income schools, but TNTP noted one major difference in the seven schools they studied. The intervention blocks were related to what the students were learning in their mainstream classrooms. This requires school leaders to ensure that interventionists, classroom assistants and mainstream classroom teachers have time to talk and collaborate during the school day.

All seven of these schools had strong principals. Although many principals came and went during the decade TNTP studied, the schools maintained strong results.

The seven schools also emphasized student-teacher relationships and built a caring community. At Brightwood, a small charter school in Washington, D.C., that serves an immigrant population, staff members try to learn each student’s name and be collectively responsible for both their academics and their well-being. During one staff meeting, teachers wrote more than 250 student names on huge sheets of paper. Teachers ticked each child with whom they felt they had a genuine connection, and then brainstormed ways to reach students without checks.

At New Heights Academy Charter School in New York, each teacher contacts 10 parents a week—by text, email or phone—and records the calls in a log. Teachers don’t just call when something goes wrong. They also reach out to parents to talk about an “A” on a test, academic improvement or good attendance, the report said.

It is always risky to highlight what successful schools are doing because other educators may be tempted to simply copy ideas. But TNTP cautions that every school is different. What works in one place may not work in another. The organisation’s advice to schools is to change one practice at a time, perhaps starting with a category where the school is already quite good, and building on it. TNTP cautions against trying to change too many things at once.

TNTP’s view is that any school can become a high-performing school, and that there are no particular educational philosophies or materials that a school must use to achieve this rare feat. Much of this is simply about increasing communication between teachers, between teachers and students, and with families. It’s a bit like weight loss diets that don’t dictate what foods you can and can’t eat, as long as you eat less and exercise more. Basic principles are most important.

Contact the staff writer Jill Barshay at (212) 678-3595 or barshay@hechingerreport.org.