A robotic exoskeleton can train people to move their fingers faster

Shinichi Furuya

A robotic hand exoskeleton could help expert pianists learn to play even faster by moving their fingers.

Robotic exoskeletons have been used for a long time rehabilitate people those unable to use their hands due to an injury or medical condition, but using them to improve the skills of able-bodied people has been less well studied.

now, Shinichi Furuya and his colleagues at Sony Computer Science Laboratories in Tokyo have found that a robot exoskeleton can improve the finger speed of trained pianists after a single 30-minute training session.

“I’m a piano player, but I (injured) my hand from practicing too much,” says Furuya. “I was facing this dilemma, between over-practicing and injury prevention, and then I thought, I have to think of a way to improve my skills without practicing.”

Furuya recalled that his teachers would show him how to play certain pieces by placing their hands on him. “Haptically, or more intuitively, I understood without using words,” he says. This made him wonder if a robot would be able to replicate this effect.

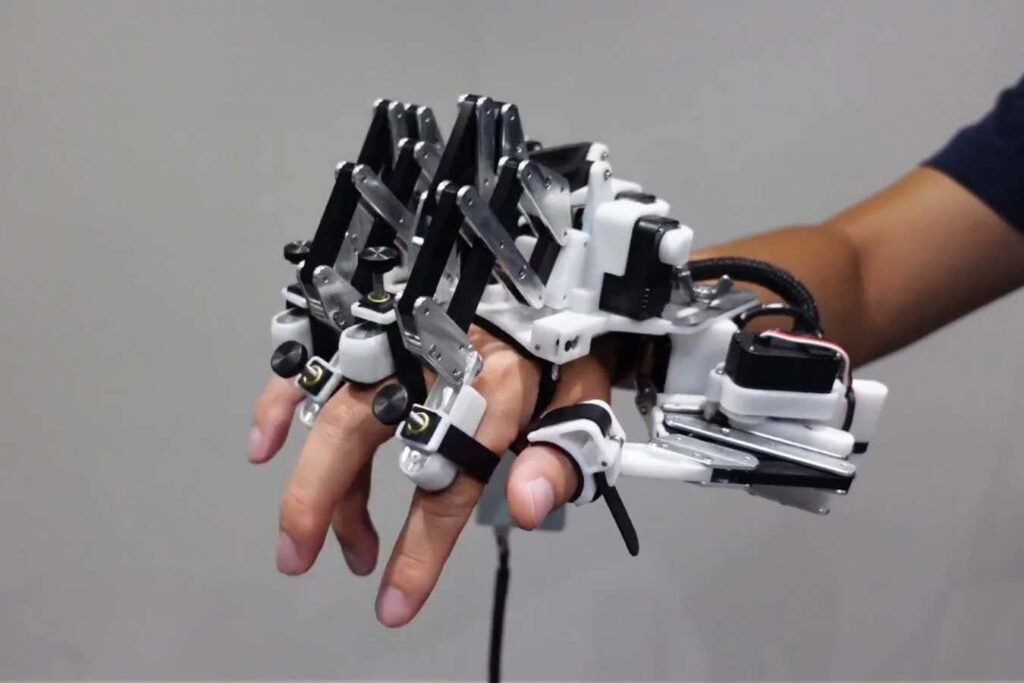

The robotic exoskeleton can raise and lower each finger individually, up to four times per second, using a separate motor attached to the base of each finger.

To test the device, the researchers recruited 118 expert pianists before the age of 8 who had played for at least 10,000 hours, and asked them to practice a piece for two weeks until they could not improve.

The pianists then received a 30-minute training session with the exoskeleton, which moved the fingers of their right hand in various combinations of simple and complex patterns, either slowly or quickly, so Furuya and his colleagues could determine which type of movement led to improvement. .

Pianists who experienced fast and complex training were able to coordinate the movements of their right hand better and moved the fingers of both hands faster, both after training and a day later. This, along with brain scan evidence, indicates that the training changed the pianists’ sensory cortices to better control their finger movements in general, Furuya says.

“This is the first time I’ve seen someone use (robotic exoskeletons) to go beyond normal dexterity to push your learning beyond what you can do naturally,” he says. Nathan Lepora at the University of Bristol, UK. “It’s a bit counterintuitive as to why it worked, you’d think that voluntarily doing the movements yourself would be the way to learn, but passive movements seem to work.”

Topics: