Hidden in the towering mountains of Central Asia, near what has been called the silk roadthey are archaeologists uncovering Two medieval cities that were inhabited a thousand years ago.

A team first spotted one of the lost cities in 2011 while wandering the grassy mountains of eastern Uzbekistan in search of untold history. Archaeologists walked along the course of the river and saw burial sites up to the top of one of the mountains. Once there, a plateau dotted with curious mounds spread out before them. To the untrained eye, these mounds wouldn’t look like much. But “as archaeologists…, (we) recognize them as anthropogenic places, as places where people live,” says Farhod Maksudov of the National Archaeological Center of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan.

The floor was also littered with thousands of pottery shards. “We were blown away,” says Michael Frachetti, St. Archaeologists from Washington University in St. Louis. He and Maksudov searched for archaeological evidence of nomadic cultures that grazed flocks in the mountain pastures. The researchers never expected to find a 30-acre medieval city at about 7,000 feet above sea level in a relatively inhospitable climate.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

But this area called Tashbulak, after the name of the area today, was only the beginning. While excavating in 2015, Frachetti met one of the region’s only residents—a forest inspector who lives with his family a few kilometers from Tashbulak. “He said, ‘In my backyard, I’ve seen pottery like this,'” Frachetti recalls. So the archaeologists went to the forest inspector’s farm, where they found his house on a familiar-looking mound.

“Sure, he lives in a medieval citadel,” says Frachetti. From there, the researchers looked over the landscape and saw even more mounds. “And we’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, this place is awesome,'” added Frachetti.

This second site, called Tugunbulak, is described for the first time in a study published on October 23 nature Researchers used remote sensing technology to map what they describe as a sprawling medieval city three miles from Tashbulak, which was integrated into the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road.

“It’s a pretty remarkable find,” says Zachary Silvia, an archaeologist at Brown University who studies this period of Central Asian history and culture. (Silvia did not participate in the new work, but a the comment it was published in the same issue nature) Although more excavations are needed to confirm the extent and density of Tugunbulak, “even if it’s half the size (estimated here), it’s still a huge discovery,” he says, and one that could force a rethink of how widespread it is. They were the networks of the Silk Road.

On traditional maps of the Silk Road, the trade routes covering the Eurasian continent tend to avoid the mountains of Central Asia as much as possible. Low-lying cities like Samarkand and Tashkent, with the arable land and irrigation necessary to sustain a vibrant population, are considered the true destinations of trade. On the other hand, the nearby Pamir Mountains, where the Tashbulas and Tugunbulas are located, are rugged and mostly uncultivated due to their altitude. (Less than 3 percent of the world’s population today lives above 2,000 meters, or about 6,500 feet, above sea level.)

However, despite limited resources and cold winters, people lived in Tashbulak and Tugunbulak from the eighth to the eleventh century. century, in the Middle Ages. Eventually, slowly or suddenly, the settlements were abandoned and left to the elements. In the mountains, the landscape changed rapidly, and the remains of cities were eroded and covered with sediment. A thousand years later, what remains are mounds, plateaus and mountain ranges that are very difficult to map with the naked eye.

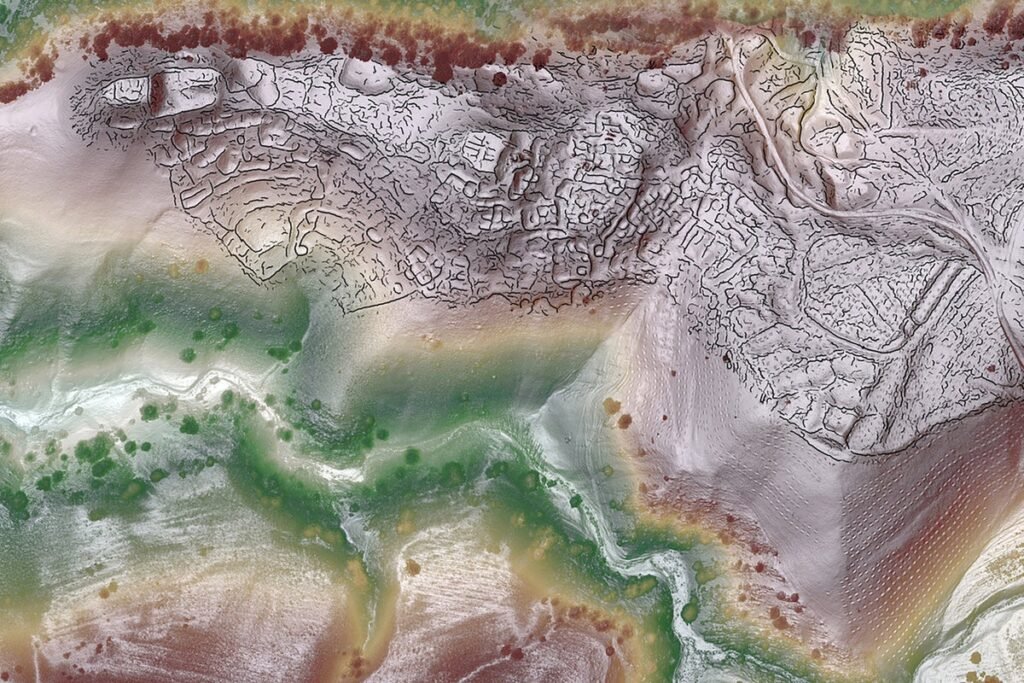

Drone view of Tugunbulak.

To get a detailed view of the ground, Frachetti and Maksudov equipped a drone with remote sensing technology called lidar (light detection and ranging). Drones are highly regulated in Uzbekistan, but the researchers obtained the necessary permits to fly at the site. A lidar scanner uses laser pulses to map features on the ground below. Technology has been increasingly used in archaeology; In recent years, it has helped discover a The lost city of the Maya, sprawled beneath the rainforest in Guatemala

In Tashbulak and Tugunbulak, it was a relief map of the sites with inch detail. Using computer algorithms, manual tracing, and excavations, the researchers mapped subtle ridges that represented walls and other buried structures.

This method has its limitations, says Silvia, namely that it often produces false positives. Also, it is impossible to confirm which features come from which period without further excavation. This work is being done in Tashbulak, but it has only just begun in Tugunbulak. (Some scans and excavations were completed in 2022, and Frachetti’s team returned to Tugunbulak last summer to continue excavation. The researchers have not yet published their findings.) For now, the lidar map of Tugunbulak appears to show a huge medieval complex, a citadel, buildings, courtyards , made up of squares and roads, bordered by fortified walls. Along with ceramics, the team has excavated furnaces, as well as traces of city workers smelting iron ore, Frachetti said.

Medieval pottery excavated in Tugunbulak.

Metallurgy can be a key part of a city’s self-sustainability at high altitude. The mountains are rich in iron ore and have dense juniper forests that could be burned to fuel the smelting process. Researchers have also found coins from all over present-day Uzbekistan, Maksudov says, suggesting the city may have been a trading hub. It does not seem to have been a mining settlement either – in Tashbulak, a cemetery contains the remains of women, the elderly and children.

“We realized that it was a large urban center that was integrated into the Silk Road network and that dragged the Silk Road caravans to the mountains … to offer their products,” says Maksudov.

“There is a relationship between these cities” between those in the highlands and those in the lowlands, says Sanjyot Mehendal, an archaeologist and director of the Tang Center for the Study of the Silk Road at the University of California, Berkeley. Silk Road trade networks were “very, very fluid,” and societies once considered peripheral and remote, like the Tashbula and Tugunbula, “were part of a network that stretched across Eurasia,” he says. “You can no longer look at these areas and perceive them as remote or less developed.”

Mehendale took part in the work at Tugunbulak after completing the lidar survey, and went on excavation last summer. Today he is most interested in reconstructing what the city was like during its lifetime. Who were the inhabitants? How did the population change over the seasons or centuries?

The answers to all these questions are probably out there, buried in the sediment. The research team, says Silvia, “has the job of a lifetime.”