The Trump administration refused to reveal how many employees left federal medical institutions amid mass cleaning. Without official numbers, PROPUBLICA addressed to the federal catalog for quantitative impact assessment.

Several news – including propublica – have used this directory Show Who enters and leaves Federal government, spot Political meetings and determine Members of the Department of Effectiveness of Government. According to several former and current employees and Documents of the Health AgencyThe HHS staff catalog helps workers find and authenticate their colleagues. HHS did not answer the propublica questions about why it does not share the data reduction data.

To understand the changes in the state over time, the propublica regularly archived The HHS catalog Ever since President Donald Trump has returned to office. In contrast to the official sets of data of state -owned workers who are often outdated by months and incomplete, the catalog data give a more relevant picture of the one who is and what does not work in the largest healthcare country.

The HHS catalog covers the staff at the department’s main office and more than A dozen medical institutions and institutionsIncluding nutrition and medicine management centers for disease control, and the National Institute of Health.

The directory gives the name of the employee, email address, agency, office and title. Some employees refer to “non -governmental”, indicating that they may work on a contract or have another temporary status.

While the official HHS Offer employment numbers Its labor force is about 82,000 employees, the catalog contained almost 140,000 records. The difference is explained by non -governmental workers such as contractors, fellows, trainees and guest researchers. Approximately 30,000 records in the catalog were clearly marked as non -governmental, but this label was far from complete. We found hundreds of workers who had the titles who assumed that they were contractors but were not designated as non -governmental.

While these workers were not directly employed by the government as civil servants, we included them in our analysis because they are crucial for agencies, especially in research institutions such as NIH, FDA and CDC. We excluded trainees, students and volunteers, as well as records of catalogs that were tied to group mailboxes or conferences, not individuals.

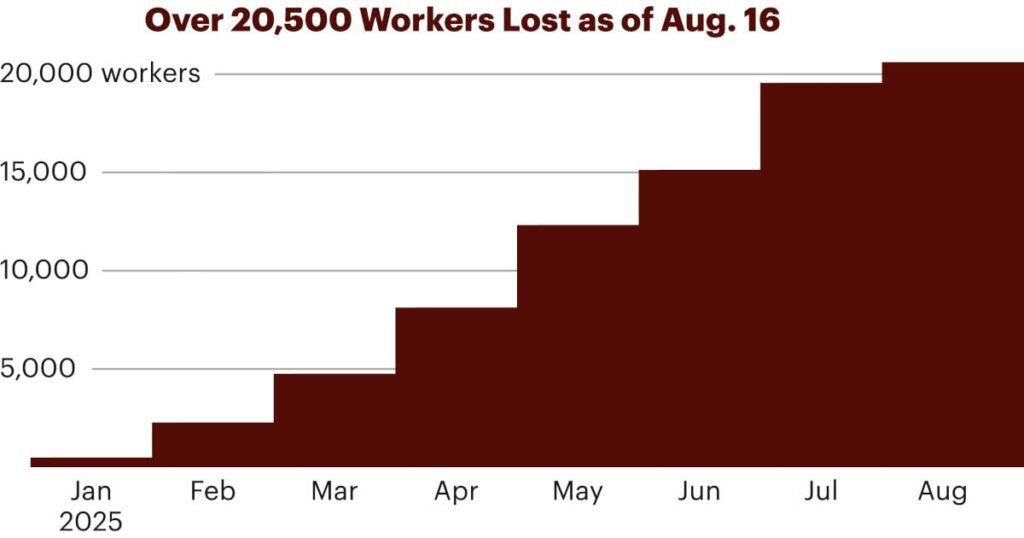

To analyze the turnover, we found when the employee’s email address first appeared. When the e -mail disappeared, we marked it as a departure. When a new one appeared, we marked it as a rental. To quantify the reduction of labor, we counted the number of records that appeared in the catalog until January 25 and disappeared on or after. We chose on January 25 to account for the delay we watched in the catalog updates. Starting with the analysis a few days after Trump has sworn, the majority of the political assigned assigned to Biden’s administration from our analysis should be eliminated, but there may be cases when the political is discarded after that date. Our analysis includes trips until August 16.

While our analysis is designed to understand the reduction of labor, not all departures are dismissal. Workers may have left for other reasons, including resignation, resignation, redemption and contracts.

To verify the catalog accuracy, we conducted an employment status check using LinkedIn, other records and interviews with open source. While we did not find the relevant, public profiles that were in line with the catalog for each person we sought, we were able to confirm employment status for dozens of current and former workers.

Some high -profile trips allowed us to check out our methodology: Doctor of Vana Prasada who was Assigned to head the FDA Biological Science Center and Studies In May, left the agency In July and resumed its role Again in August. The catalog data clearly reflects each of these changes in employment.

We also wanted to understand the role of lost workers and how their trips will affect their agencies. To do this, we counted on the “organization” in the catalog, which allowed us to bind employees with their specific office within the HHS by the public organization schedules. In large agencies, this field turned out to be incredibly valuable to understand the exact divisions where the losses occurred.

The headlines in the catalog are controversial, so we used the local classroom classifier to assign each name to one of the four major groups: science/health, regulators/matching, technology/IT and other. We handcuffed the titles of work in each category and considered former employees on LinkedIn to confirm their work status and the nature of the work they carried out. Our results for NIH are insufficiency, as 78% of records do not list roles. We counted on the most recently listed role of workers, which could reflect the work that a person had only briefly.

Employee catalog is the best data to which we have, but it is not without restrictions.

Our understanding is that each entry is an individual employee. There are some cases where our analysis is twice considered the employee because they have been seen in two agencies or had several email addresses, probably from the name change or correction of officials. Our review of these records suggests that these types of duplicates are rare.

Our strict review has revealed some cases where the catalog is not aware. We have excluded Medicare & Medicaid centers from our analysis because its directory has not received regular updates. We also excluded the Indian Health Service because it has an abnormally high level of taking.

We do not consider there about 2500 records that can be found in search, but in which there are no detailed records or do not transfer email.

Sophie Chu included in the data report.