Georgia Republican Gov. Brian Kemp said 345,000 people would be enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program, which has strict work requirements — so far, only 5,118.

In 2023, when Georgia launched Medicaid, which was tied to strict work requirements, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp framed it as a way to help people get health insurance. He made the announcement despite the state refusing — and still refusing — to expand the program under the Affordable Care Act. The new plan will be “innovative”, Kemp saidputting “Georgians and their access to health care first.” He said 50,000 people would join in the first year and that eventually 345,000 eligible people would be registered.

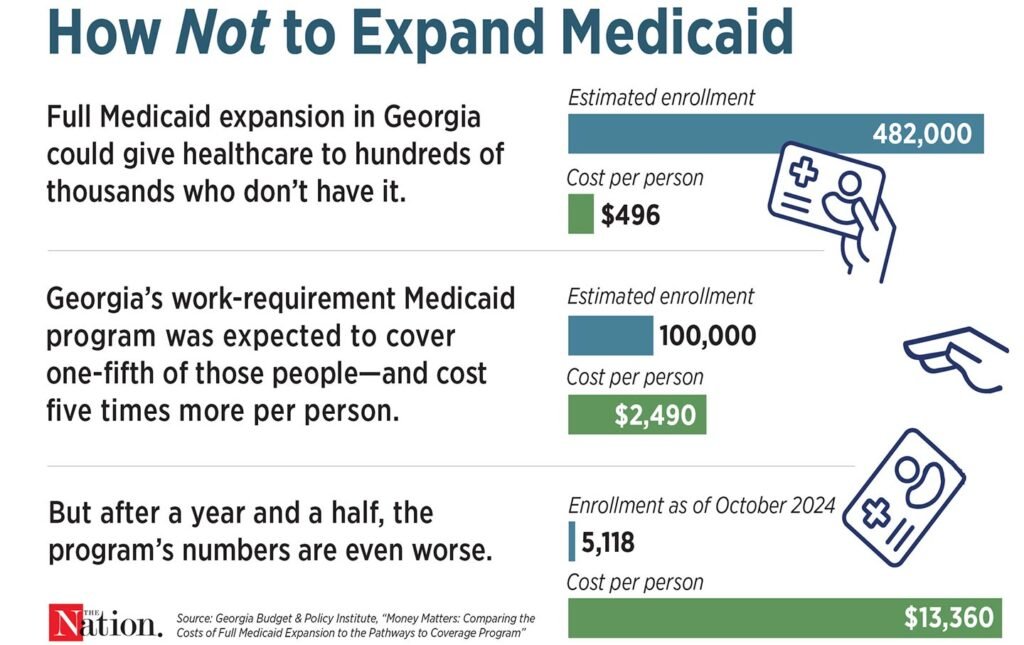

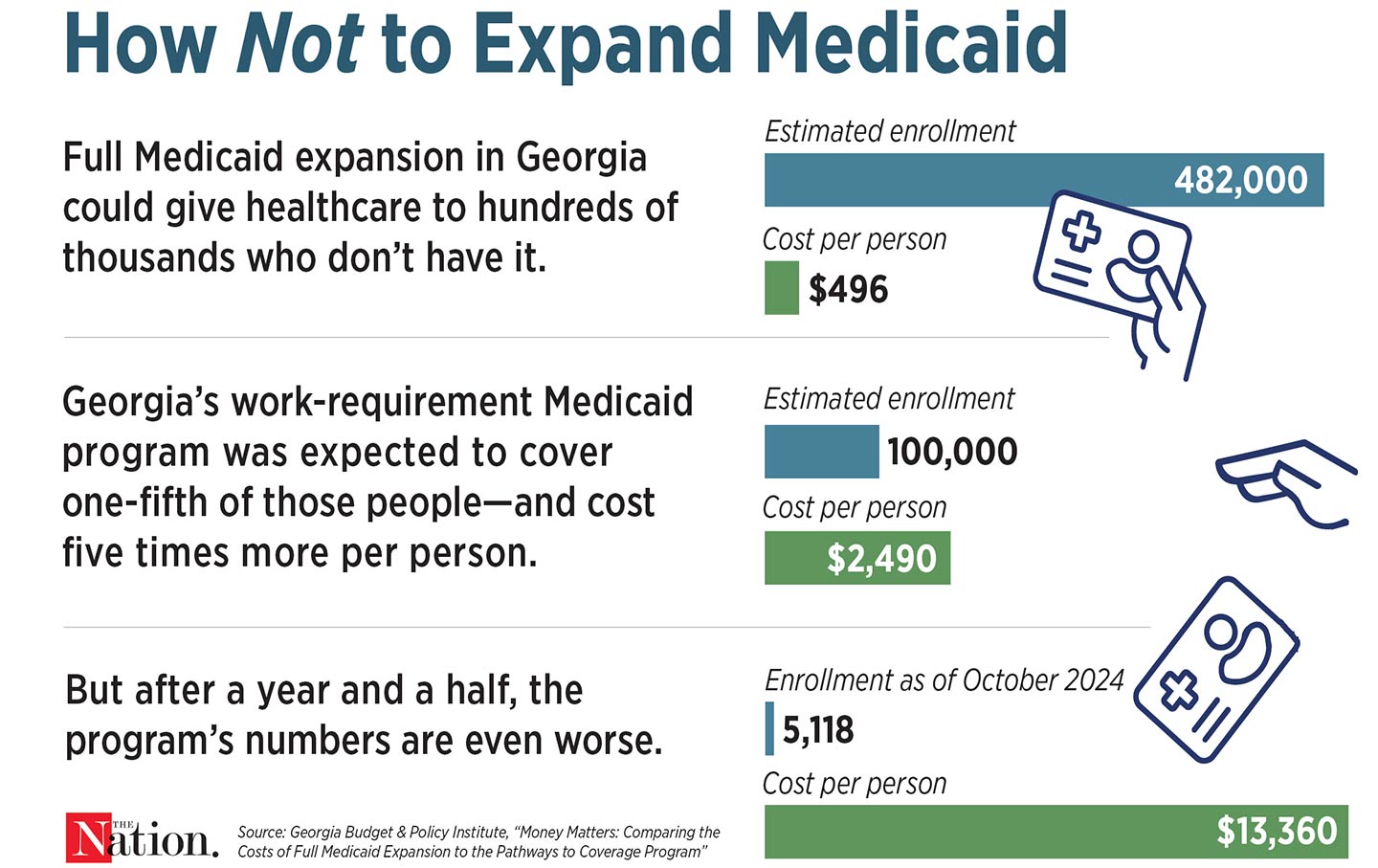

A year and a half later, his promises did not come true: at the end of October, only 5118 people were enrolled in the state’s Medicaid work requirement program is 5 percent of people who said they wanted to sign up.

Part of the problem is that work requirements in Georgia are particularly strict. As in other states that have proposed making Medicaid recipients prove they work, people in Georgia who make up to $31,200 for a family of four and want to participate in the new program must routinely report that they either working or commuting to college, attending vocational training, or volunteering at least 80 hours per month. But unlike other states, Georgia’s rules apply to people age 64 and older, as well as those who care for their children or other relatives full-time, don’t have transportation, or are dealing with drug addiction. Other states have also proposed giving people a few months as a grace period to comply before losing coverage; In two months, Georgia can snatch it.

The state also made it difficult for people to enter. Georgians need to get through “long questionnaires and technical language”, Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported. Document uploading tools are difficult to use; sometimes the website just stops working. In June, 1,459 people tried to sign up for the program but failed because they couldn’t report their work hours to qualify for coverage.

The state spends a lot of money on this. A year after its launch, the program cost nearly $58 million, most of which went to administrative and consulting fees, not medical costs.

Georgia could simply expand Medicaid to all low- and moderate-income residents, which would cost the state less and go much further toward Kemp’s intended goal of expanding access to health care. Georgia’s regular Medicaid program is already one of the stingiest in the nation: Parents can enroll only if they make less than $10,000 a year for a family of four, and adults without children can’t join at all. If Georgia were to expand Medicaid, 359,000 people would be able to enroll. It would also be much cheaper: Instead of spending $2,490 to enroll each of the expected 100,000 people in the work requirement program, the state would pay just $496 per person in a fully expanded Medicaid program. But in March, state lawmakers rejected a proposal to expand Medicaid.

The high cost and ineffectiveness of the work plan should not have surprised Governor Kemp. In 2018, Arkansas became the first state to implement a work requirement for Medicaid enrollees. The program had no discernible impact on employment, and more than 18,000 people lost Medicaid coverage because they failed to meet the requirements or complete the paperwork. It also cost the state about $26 million. Such programs in other states had even higher price tags; in 2019 the federal government is evaluated that Kentucky’s work requirements will cost the state $272 million.

But even in states that have expanded Medicaid and not implemented pointless work requirements, paperwork prevents millions of Americans from accessing health care. At the start of the pandemic, Congress passed legislation barring states from deporting anyone during a public health emergency. That ended in April 2023, and states started forcing people to regularly prove they were still eligible again. Since then, more than 25 million people have lost their insurance, almost 70 percent those due to procedural or administrative problems.

The pandemic has proven that we can simply keep people in Medicaid, giving them access to care that reduces medical debt, improves health, and reduces mortality. During the public health emergency, more than 21 million people signed up when paperwork was suspended. But the country remains obsessed with making people prove they’re worth insurance, not just helping them stay healthy.