I wanted to look at the relationship between family structure and student achievement according to family income. Single-parent families are much more common in low-income communities, and I did not want to confound achievement differences by income with achievement differences by family structure. For example, 43 percent of low-income eighth graders live with only one parent, compared to 13 percent of their high-income peers. I wanted to know if children who live with only one parent do worse than children with the same family income who live with both parents.

To analyze the latest data from the 2024 NAEP exam, I used NAEP Data Explorera public instrument developed by the ETS testing organization for the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). I told an ETS researcher what I wanted to know, and he showed me how to generate crosstabs, which I then replicated independently across four tests: fourth- and eighth-grade reading and math. Finally, I cross-checked the results with a former high-ranking official at NCES and with a current board official who oversees NAEP assessment.

The analysis reveals a striking pattern.

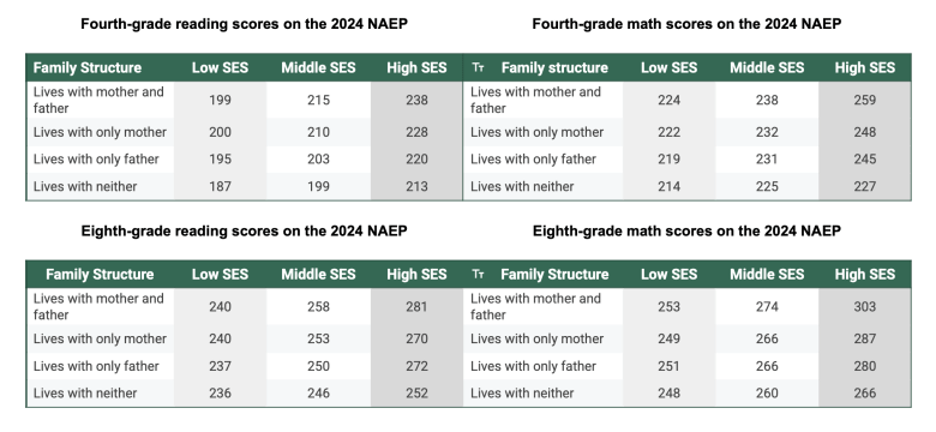

Among low-income students, achievement differs little by family structure. Fourth- and eighth-graders from low-income households perform about the same whether they live with both parents or just one parent. Two-parent households do not confer a measurable academic advantage in this group. Fourth grade reading is a great example. Among the socioeconomic bottom third of students, those living with both parents scored 199. Those living with only one mother scored 200. Scores were nearly identical and even slightly higher for children of single mothers.

However, with increasing socio-economic status, differences in family structure become more pronounced. Among middle- and high-income students, those living with both parents tend to score higher than their single-parent peers. The gap is greatest among the wealthiest students. In fourth-grade reading, for example, higher-income children who live with both parents scored 238, a full 10 points higher than their peers who live with only their mothers. Experts debate the meaning of a NAEP score, but some equate 10 NAEP scores to a school year’s worth of learning. This is significant.

Family structure matters less for low-income student achievement

Still, it’s better to be rich in a one-parent household than poor in a two-parent household. High-income students raised by a single parent significantly outperformed low-income students living with both parents by at least 20 points, highlighting that money and the benefits it brings — such as access to resources, stable housing and educational support — matter far more than household composition per se. In other words, income far outweighs family structure when it comes to student achievement.

Despite the NAEP data, Jonathan Butcher, acting director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, maintains that family structure matters a lot for student outcomes. He points out that research because the landmark 1966 Coleman Report consistently finds a connection between the two. More recently, in a American Enterprise Institute-Brookings 2022 Report15 researchers concluded that children “raised in stable married-parent families are more likely to excel in school and generally have higher GPAs” than children who are not. Two recent books, Get Married (2024) by Brad Wilcox and The Privilege of Two Parents (2023) by Brad Wilcox also make the case and indicate that children raised by married parents are about twice as likely to graduate from college as children who are not. However, it is unclear to me whether all of this analysis disaggregated student achievement by family income, as I did with the NAEP data.

Family structure is a constant theme for conservatives. Just last week, the Heritage Foundation released a report on strengthening and restoring American families. In July 2025 newsletterRobert Pondicchio, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, wrote that “the most effective intervention in education is not another literacy coach or SEL program. It’s Dad.” He cited a June 2025 report, “Good fathers, thriving children,” by scientists and advocates. (Disclosure: A group led by one of the authors of this report, Richard Reeves, is among the funders of the Hechinger report.)

This conclusion is partially supported by the NAEP data, but only for a relatively small proportion of students from higher-income families (The proportion of high-income children living with their mother alone varies between 7 and 10 percent. The proportion of single parents is higher for eighth-graders than for fourth-graders.) For the low-income students who are the primary concern of Pondiscio and the researchers, this is not the case.

Data has limitations. The NAEP survey does not distinguish between divorced families, households headed by grandparents, or same-sex parents. Joint custody arrangements are likely to be grouped with two-parent households, as children may say they live with both mother and father, if not at the same time. However, these nuances are unlikely to change the main finding: for low-income students, academic outcomes are largely similar whether they live with both parents all of the time, some of the time, or live with only one parent.

The bottom line is that calls for new federal family structure data collection like those outlined in Project 2025 may not reveal what advocates expect. A family’s bank account is more important than a wedding ring.