Chicago Art Institute announced recently that he returned to Nepal sculpture that had at least a quarter of a century. Noticeably left in a press release: that the sculpture was a gift from a wealthy Chicago donor.

This inauguration Incorrectly built its collection of hundreds of South Asian works And why the art institute, which houses some of their collections in their galleries alsdorf, is reluctant to return these works to countries with convincing requirements.

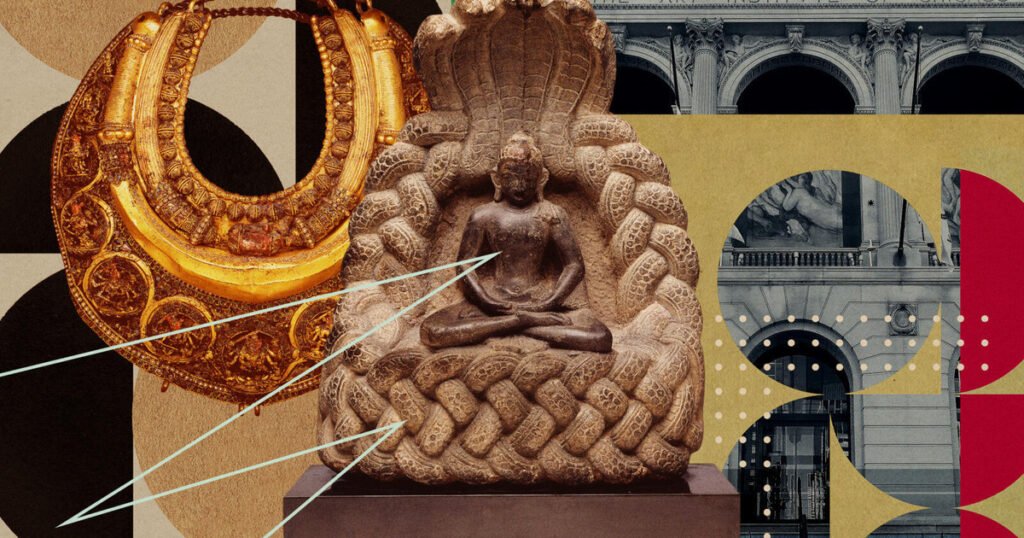

The 12th-century sculpture, which returned to Nepal, is called “Buddha, leaning by the King of Mahalinda” and about 17.5 inches. The Art Institute stated that it was stolen from the Chatmond Valley, though it is unclear when the theft was or how and when Alsdorf acquired this work.

It was among more than a dozen works defined by PROPBLICA and CRAN’s Chicago Business in 2023, as claims against their other countries, including Nepals. In my time, Each work belonged alsdorfsInvestigation found.

The Art Institute devotes the page on the Internet by works that were removed from its collection, the processes of processes are called deoxceys. But unlike other pages on your site about works of art or works at the exhibition, pages for subjects, The list is not mentioned alsdorfs.

Melissa Kerin, Director of the MUDD Ethics Center at the University of Washington and Lee in Virginia, and Professor of Art History, who specializes in South Asian and Tibetan art and architecture, said the art institute is trying to have it in both methods of repatriation of the Buddha. According to it, she is looking for a loan for the origin and return of the Buddha, but does not reveal the participation of her own donors.

“It looks active. They get rid of the problematic object,” Kerin said. “But people will never know about the full information about it. They produce face to Alsdorf and their relationship with them and all donors. They have something to lose.”

Alsdorf, who lived in Chicago, had an influence on the world of arts, donating more than $ 20 million to the Life Institute. James Alsdorf, the son of a Dutch diplomat and a business owner who produced glass coffee, was chairman of the museum council from 1975 to 1978. He died in 1990.

Marylin Alsdorf was a confidant of the museum and the president of the woman’s council. She exhibited her collection and her husband at the Museum in 1997, and the alsdorf galleries opened in 2008. She died in 2019.

The controversy surrounded a large collection alsdorfs for decades. In the 1970s, the Thailand government sought the return of the stone carving, and after the protest outside the museum was allotted.

In 2002, a man in California sued Marylin Alsdorf to restore Picasso’s painting called “Femme En Blanc” or “Lady in White”, which, as he allegedly belonged to his grandmother before the Nazis was plundered during World War II. Marylin Alsdorf eventually paid a man $ 6.5 million in exchange for the painting. She said nothing wrong with getting this.

The son of Alsdorf, Jeffrey, is included in the tax forms as President of the Alsdorf Foundation, which gave the art institute an educational grant or a contribution of $ 40,000, recently in 2023. He asked about the repatriation of the Buddha, he replied, “I hope the deal is experiencing and everyone is satisfied.” Then he put the phone on the reporter.

The official at the Nepal Embassy in Washington stated that the transaction had survived and that it was present at the ceremony where the Buddha was handed over to Nepalese officials. Several representatives of the museum participated in the ceremony and spoke about the continuation of work with Nepalian officials.

A press secretary of the Institute of Arts said in a statement that the museum “seeks to determine priorities for origin in various departments that include our art collection.” Over the past five years, the statement continued, the museum has created positions dedicated mainly to origin, including the role of the Executive Director of Origin. Earlier, the museum stated that many works donated by alsdorf were accepted and checked by standards.

The press secretary said in a statement that the museum returned two works last year from its permanent collection to its countries of origin and returned additional works that were on the loan over the past few years. The secretary -secretary did not submit details about these repatriation.

According to Buddha’s statement, he was a “priority of the study” for the museum. After receiving new information about the sculpture, the Art -Institute turned to the Nepal government in 2024 to start the process of returning to the country.

The museum appears to be attracted by the difference between the return of the Buddha and the request from Nepal for the return of Taleju’s necklaces, saying: “The origin of this object is separated from other objects in our collection.”

The press secretary said in a statement that the museum had sent a letter to the Nepal Government in May 2022 asking for additional information about the necklace, but that he was still waiting for an answer. However, the museum stated that it has a “constant dialogue” with Nepalian officials and will continue to work with them. The embassy spokesman did not answer the propublica questions about the necklace or the museum’s request for additional information.

Deviations, the Nepal’s heritage restoration campaign, said the Art Institute deliberately complicates the process for Nepal.

“I believe that the burden of evidence should be at the Chicago Art Institute to prove that it belongs to them,” he said about Taneju’s necklace. “This is a violation of our cultural rights.”

Erin Thompson, Professor of Art Crime at Criminal Justice College John John in New York, stated that the policy of the Institute of Art concerning the objects that he returns – for example, can complicate the researchers to track the origin of the object. It can also raise doubts in other facilities in the collection.

“You don’t erase this story to save someone a little embarrassment,” she said.

The Art Institute refused to ask for an interview, but in response to written questions, the spokesman said he followed the policy of the wide museum for disclosure of history and ownership of de-acessa objects. After the object is no longer in the museum’s collections, it does not include the origin of the item on its site – practice that some art historians criticize.

The investigation of information organizations was focused on a decorated work called Tameju Ringlace, inscribed in gilded copper work, decorated with semi -kicks and intricate structures. The 17th century King of the 17th century, the Kings of the Hindu goddess Taij, proposed.

Officials with the government in Nepal, as well as the activists, gathered great attention to the king, who, in their opinion, were stolen during the political upheaval in the country. It remains noticeably presented in the Gallery Alsdorf, although some say it is offensive to reflect such holy work in public.

Activists stated that their disappointment at the Institute of Art spread to other works.

“It is not just about the necklace,” said Sanji Zimbatar, the lawyer and secretary of the Nepal’s heritage restoration campaign, the organization seeking the return of a number of works taken from the country. “We are talking about many other cultural properties. There is a great disappointment at the Chicago Art Institute.”