January 23, 2025

5 read me

Saturn’s rings are fading, but they will return

This year, from Earth’s perspective, Saturn’s rings will appear almost edge-on, making them almost invisible

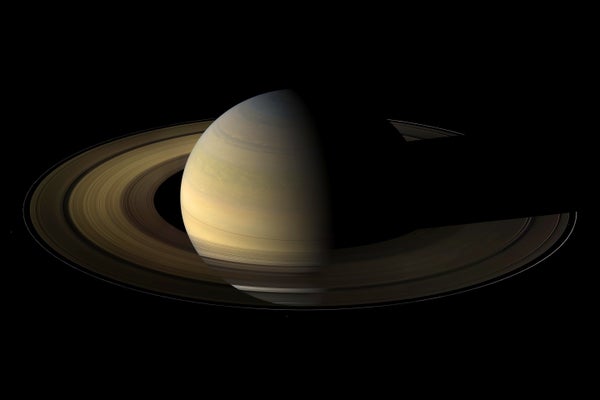

Saturn’s rings, imaged here by NASA’s Cassini orbiter, are one of the most reliable sights in the solar system. But sometimes they seem to disappear from Earth.

NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

I recently noticed something strange about Saturn while admiring it near bright Venus in the southwestern night sky. Any nearby object our evil twin sister planet by comparison, it can be Venus so bright that it is usually mistaken for an airplane or a UFO—but Saturn looked good. It’s almost on the other side of the sun from us now, so it’s almost at its maximum distance from Earth, so it’s a little dimmer than usual. But still, it seemed particularly dark.

Then I remembered: Saturn’s bright rings are fading, at least from our view here on Earth. The normally wide rings appear much thinner than usual, almost like a planetary line. Without adding their many reflective pieces of ice Our view of Saturn’s brightnessthe planet is actually less than half as bright as it can be at other times.

Don’t worry, Saturn’s magnificent rings are still there! There are two reasons why they are almost invisible: one is that they are almost impossibly flat, and the other is that the dance between the orbits of Saturn and the Earth affects our viewing angle.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

Saturn’s rings aren’t the most obvious thing about the planet, they’re arguably the most magnificent structure in the entire solar system. The main rings are about 280,000 kilometers wide; If placed between the Earth and the moon, they would cover more than two-thirds of that gap! At a distance of more than a billion kilometers from Saturn to Earth, the rings, as large as they are, are invisible to the naked eye, but barely: as soon as we began to scan the sky with telescopes, the rings were visible, even more so. if their true structure remained mysterious.

Galileo saw the rings through his crude telescope in the 17th century. At the beginning of the century, but he did not have enough resolution to see its true form, and called them the “ears” of Saturn. Decades later The Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens realized that the planet was surrounded by a ring that was “not touching anywhere”, as he wrote in the book Systema Saturnium. A number less than the physicist James Clerk Maxwell– who determined the equations for electromagnetism on which our technological civilization is based – was the first to demonstrate that this ring could not be solid, otherwise it would be torn. The inner rim would spin around Saturn much faster than the outer rim, crushing it. From this, it was seen that the rings of the planets (in the plural) must be composed of pieces of material that are too small to be seen by any telescope from Earth. More modern observations showed that these parts are almost pure water ice, which is why they are so bright; ice is an excellent reflector of sunlight. And modern research also showed that most of these parts are smaller than an average car. It has to be quadrillion from them

Comprised of images from the Hubble Space Telescope, this animation shows the changing view of Earth around Saturn’s rings between 2018 and 2024.

NASA, ESA, Amy Simon (NASA-GSFC), Michael H. Wong (University of California), Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

The rings were probably formed by an impact from an icy moon of Saturn, tough, an approaching object, perhaps even another moon. interestingly, it is not clear when this happened. Research published in journal Icarus in 2023 studied the rate of accumulation of dark micrometeorite dust in otherwise bright rings and found that the rings were young, cosmically speaking: only 100 million to 400 million years old. On the other hand, Research published in the journal at the end of 2024 Nature Geoscience that the “pollution” rate of that dust is not as fast as it was thought; high-velocity micrometeorite collisions ionize the ring particles, giving them an electrical charge. This exposes them to Saturn’s strong magnetic field, which pulls material away, slowing the rate at which the rings darken. This means that the rings can be much older.

Even today, centuries after their discovery, the rings still pose fundamental mysteries.

However, how they formed after the initial collision is fairly well understood, and explains their flatness, if not their age. Because of the orbital motions of Saturn’s moon and its impactor, the debris would first form a long stream, most of which would be in the direction of that moon’s orbital motion. Saturn’s other moons orbit above its equator, so its material would likely end up in a similar configuration. Also, since Saturn is not a perfect sphere, but rises at the equator from its rapid 10.5-hour rotation period, the thick half of the planet would throw debris into orbit directly above the equator; therefore a ring impact would form a flat disc.

And I mean it flat. Despite hundreds of thousands of kilometers, they are rings terribly thin, up to one kilometer vertically. In some places the rings are only 10 meters high, as tall as a three-story building. As huge as the rings, if they and Saturn itself spanned 28 centimeters (11 inches), the length of a standard piece of paper, the rings would be 100 times as thin as paper! Finally, Gravitational interactions with Saturn’s large moons pull these ring particles into slightly different orbits. Over time, they have created thousands of individual rings, as well as a few gaps between them. So, when viewed from above, the rings are the source of drunken jaws. From the side, however, they are knife-thin and very difficult to see.

That’s where we find ourselves now. Saturn, like Earth, has a large axial tilt, tilted more than 26 degrees from the plane of the ecliptic that all the major planets orbit. (Earth is tilted 23 degrees.) This means that during Saturn’s northern summer, its north pole is tilted toward the sun. From Earth, much closer to the sun than Saturn, we would be looking “down” on the rings, seeing them in all their glory.

Saturn’s orbit is about 30 years, so for much of Saturn’s year, we see the rings clearly. During Saturn’s equinoxes, however, the rings are seen closer to Earth, and indeed specifically seen from the sun at the edge. But because Saturn’s orbit around the sun is very slightly tilted relative to Earth’s, we see the rings right on edge at Saturn’s equinox when Earth also passes through the plane of the rings. This can happen twice when the Earth passes “up” the plane near the equinox and then “down” again about six months later, effectively obliterating Saturn’s rings from our view.

And it just so happens that Saturn’s autumnal equinox will occur in May 2025. And on March 23rd our planet will pass through the plane of the rings, so at that time the action will reach a peak where the rings will disappear before slowly shifting back into view.

But there is a catch: on that date in March, Saturn will be only 10 degrees from the sun in the sky, and it is very difficult to observe. Bad timing! While Saturn will pass through Earth’s orbital plane again in mid-November, by then Saturn’s axial tilt will have tilted the rings slightly from our vantage point, so we’ll only see them. very nearly on the edge The good news is that in November, Saturn will be easily visible in the southern sky at dusk, and will still appear almost ringless through a telescope. Check to see if there is an observatory or astronomical society hosting a viewing session near you!

I’m looking forward to taking a look myself; Saturn without rings will be very rare, and something I haven’t seen in over seven years. But I also hope that time will go on and the planet will shine again as those glorious rings reappear. Somehow, Saturn wouldn’t be Saturn without them.