In Washington and most state capitals, “political principle” has become an oxymoron, with simple political honesty largely trumping crude partisanship, self-promotion, and conspiratorial nepotism.

Or should it be?

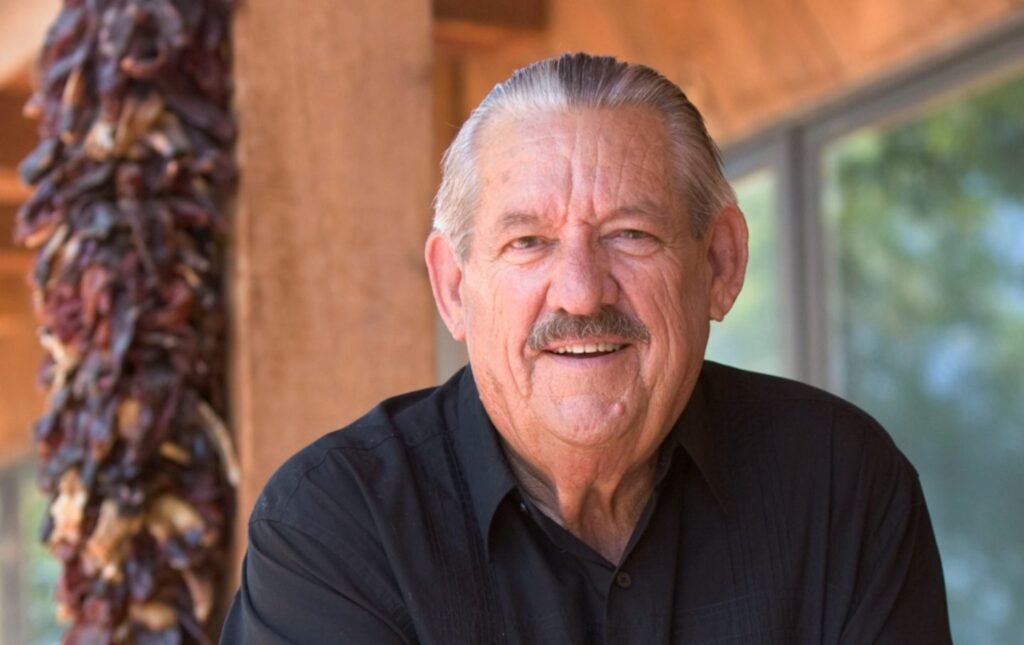

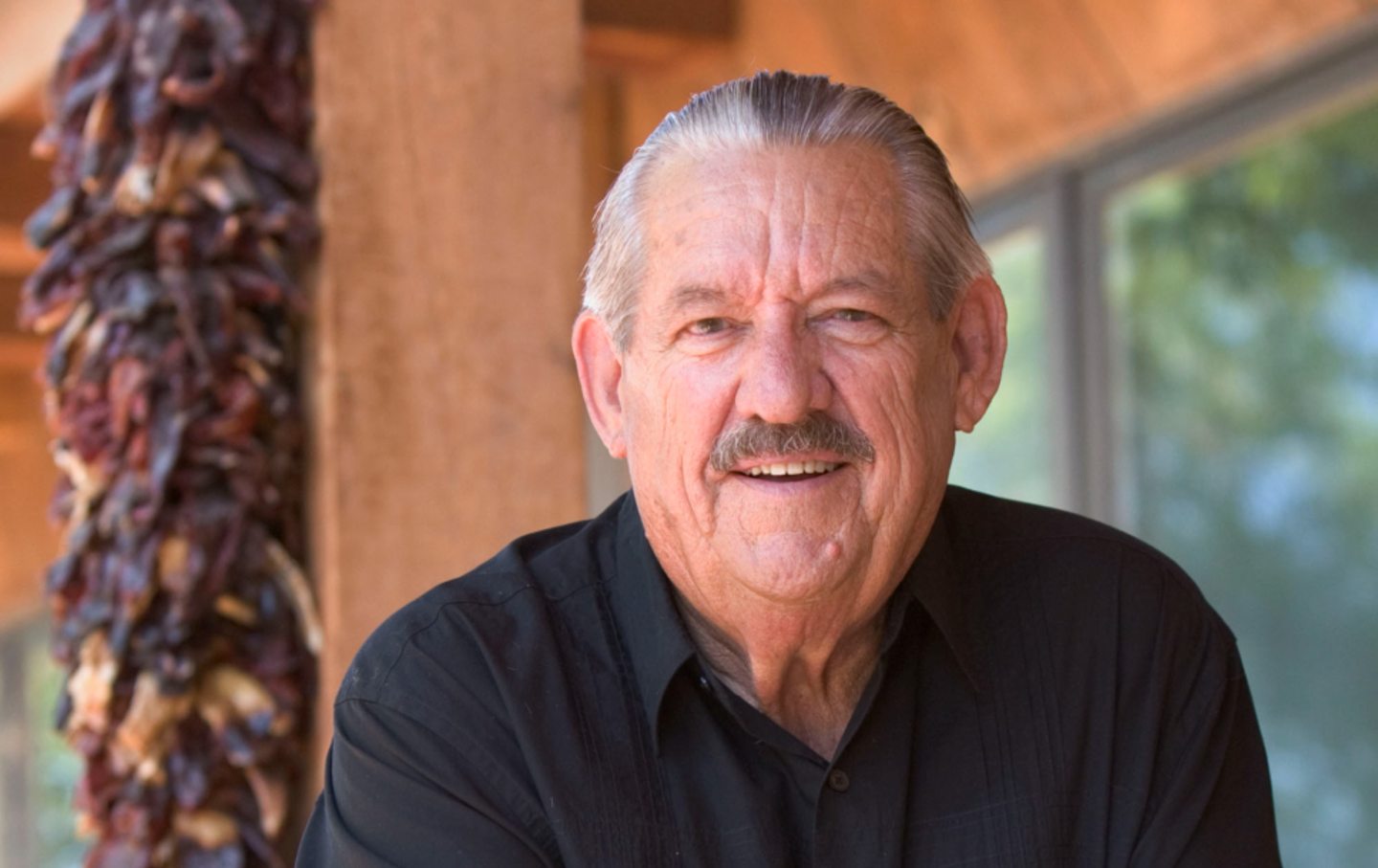

No. I knew and worked with a US senator who regularly used his political prominence to achieve a little more economic and social justice in our country: Fred Harris, who died last month at the age of 94.

The beauty of Fred was that he was real—a down-to-earth man who rose from the red dirt of rural Oklahoma to national political heights without being consumed by his own ego. Born into an impoverished family of sharecroppers and day laborers, he remained fully immersed in the anti-establishment, egalitarian values and outsider spirit of hard-line prairie populism.

Harris lost as many battles as he won, but throughout his long life he did not hesitate to take on the Powers That Be on behalf of the Powers That Be, embracing the wisdom of the old cowboy maxim, “Tell the truth, but ride fast.” horses”.

Fred was a role model and mentor for my own populist pursuits, and we joined together as co-conspirators in a wide range of endeavors, from the near-defeat of Earl Batz’s appointment as Nixon’s “agribusiness” secretary to the creation of the American People’s Wildlife Foundation. His 1976 presidential campaign, when I was national coordinator, was particularly wild.

Fred threw down the populist gauntlet at the start of his independent challenge to the wealthy elites who control both parties. “It’s a question of privilege,” he said. “Too few people have all the money and power.” Adding unequivocally: “The wide spread of economic and political power must be the express purpose—the stated purpose—of government.”

He brought this poignant message to people across America in our low-dollar grassroots run. I remember, for example, a meeting in Omaha where a member grumbled that government spending was so out of control that the city was paying garbage collectors $5 an hour. Fred interrupted him immediately, asking curtly, “Is that too much?” The participant was shocked by the collision. “How much will it take you to do this job?” – asked Fred, bursting with genuine anger. He lost this guy’s vote, but he got big points for his honesty.

One more moment. When most of the nation’s political luminaries lose a race, they never leave Washington. Instead, they become highly paid lobbyists or end up in corporate-funded think tanks. But Fred just packed up and left the camp for New Mexico – not for retirement, but for work. For the next 50 years he worked as a “citizen politician”.

Fred nurtured student activists as a popular professor at the University of New Mexico, served as chairman of the state Democratic Party to help revitalize the party, wrote more than 20 books, held frequent fundraisers for progressive candidates, and created an internship program in Washington to help underprivileged students. Indians find opportunities in the national government. And that was just the beginning. He was also a noted storyteller who loved a good story and laugh and was a loyal friend to many, including me.

The final story from Fred’s childhood is about all of us fighting for justice and fairness today, often against great odds. Farming on tenant farms, he noted, is hardly a bucolic experience. Even at the age of 5 or 6, he was expected to help with the exhausting workload of the family.

Before dawn, his father would get him and a couple of cousins out of bed to set up two draft horses so they could be hitched to plows or other farm equipment. The crew was supposed to be in the field at dawn, but first Fred’s God-fearing mother insisted that they all gather in the kitchen for prayer. Father was impatient with this delay. The moment Mom finally said Amen, Dad barked, “Hold ’em, boys.”

Fred told me he was 13 years old before he realized that when he was in church and the preacher said “Amen,” he shouldn’t end the prayer by saying, “Hook ’em up, boys.”

But I’m sure Fred would tell us progressives that we urgently need to cement our populist principles these days by applying them to America’s political arena. In my view, Harris was not some famous “great man” but something less pretentious and more useful: a decent man.

popular

“Swipe to the bottom left to see more authors”Swipe →

More from Nation

Last time, the courts were an important force in checking the Trump administration. This time they can give the check again — if we press.

The Democrat from California explains why it has been important to her during her 25 years in Congress to “tear down, dismantle and build what is fair, just and right.”