“It shows how literature … can trace a different path for memory, alongside historical narrative.”

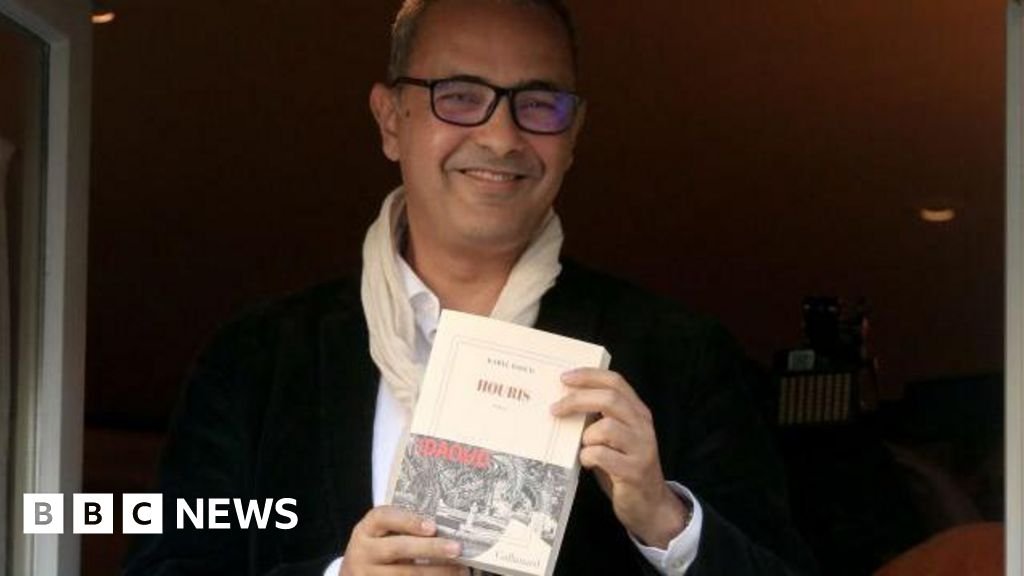

The irony is that there is little in the Algeria will most likely read it. The book does not have an Algerian publisher; the French publisher Gallimard was excluded from the Algerian Book Fair, and the news of the success of Daoud Goncourt – a day later – was still not reported in the Algerian media.

Worse, Dowd – who now lives in Paris – could even face criminal charges for talking about the civil war.

The 2005 “Reconciliation” Act makes “instrumentalizing the wounds of a national tragedy” a crime punishable by prison.

According to Dowd, the effect is to make the civil war – which traumatized the entire country – a non-issue.

“My 14-year-old daughter didn’t believe me when I told her what happened because war is not taught in schools,” Dowd told Le Monde newspaper.

“I cut some of the worst scenes I’ve written. Not because they were untrue, but because people won’t believe me.”

Daoud, 54, had first-hand experience of mass killings as he was working as a journalist for the newspaper Quotidien d’Oran at the time. In interviews, he described the gruesome routine of counting bodies, then watched as authorities changed his count — up or down — depending on what they wanted to convey.

“You develop a routine,” he said. “Come back, write your piece, then get drunk.”