Thirty-seven percent of students who adhered to the Promise scholarship program earned a two-year associate degree within three years, compared to only 11 percent of students who did not maintain eligibility, often due to incomplete financial aid documents , incomplete work hours that are required, or failure to remain enrolled in college at least part-time. Tennessee projected that the scholarship program from its inception would produce a total of 50,000 college graduates by 2025, administrators told me in an interview.

Before the tuition-free program went statewide, only 16 percent of Tennessee students who started community college in 2011 earned an associate’s degree three years later. The graduation rate then rose to 22 percent for students who started community college in 2014. At the time, 27 Tennessee counties had launched their own tuition-free programs, but the statewide policy had not yet taken effect.

By 2020, when statewide tuition was in effect for five years, 28 percent of Tennessee community college students had earned a degree in three years. Not all of these students participated in the free tuition program, but many did.

It is unclear whether the free tuition program is the driving force behind the rising graduation rate. It is possible for motivated students to sign up for it and follow the rules of the scholarship program and still graduate in greater numbers without it. It’s also possible that unrelated national reforms, from increased federal financial aid to academic advising, helped more students reach the finish line.

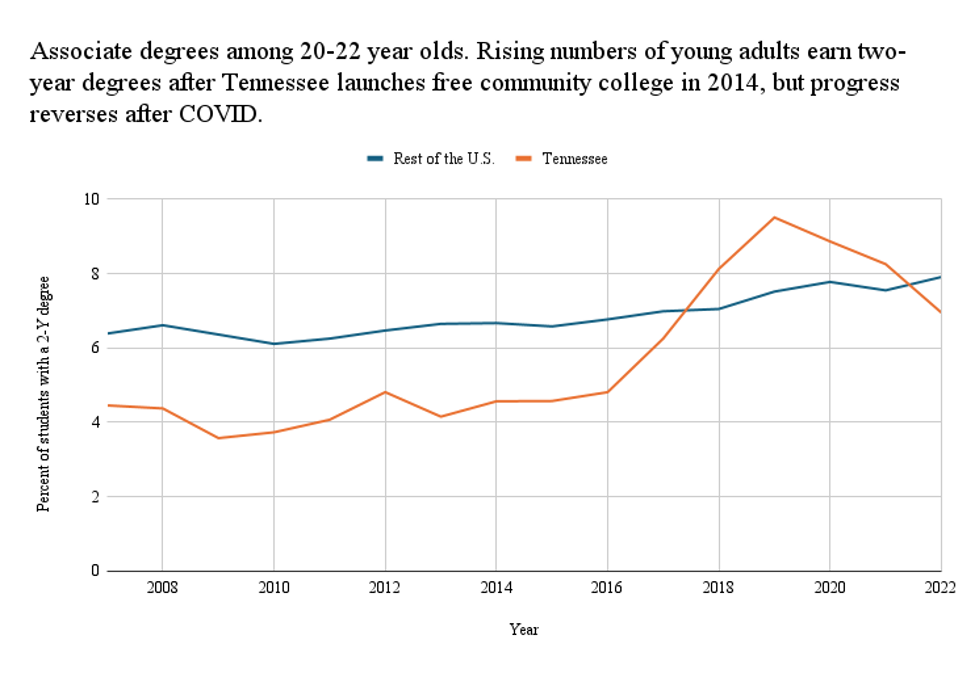

I spoke with Celeste Carruthers, an economist at the University of Tennessee Knoxville who studies the tuition-free program in her state. She’s currently crunching the numbers to see if the program is leading to an increase in graduation rates, but the signs she’s seeing now give her “reason for optimism.” Using data from the US Census, she compared college success rates in Tennessee to the rest of the United States. In the years immediately following the state’s scholarship program, beginning with the high school class of 2015, there was a notable spike in the share of young adults with associate degrees a few years later, while associate degree attainment elsewhere in the nation has improved only slightly . Tennessee quickly went from a laggard in young college achievement to a leader — at least until the pandemic hit. (See graphic.)

While there will likely be ongoing evaluation of the Tennessee program, researchers and program officials point to three lessons learned so far:

- The scholarship program has not helped many low-income students financially. The federal Pell grant of $7,395 far exceeds the annual tuition and fees at Tennessee’s community colleges, which hover around $4,500 for a full-time student. Community college was already free for low-income students, who make up roughly half of the students in Tennessee’s free college program. Like other free college programs statewide, Tennessee’s program is structured as a “last dollar” program, meaning it is paid only after other forms of financial aid have been exhausted.

This means that tuition grants have gone primarily to students from higher-income families who do not qualify for a Pell Grant. In Tennessee, the funding source is the state lottery. Approximately $22 million in lottery revenue was used to pay for community college tuition in the past year.

- Free tuition alone is not enough help. In 2018, Tennessee added coaching and mentoring for low-income students to give them extra support. (Low-income students did not receive any tuition subsidies because other sources of financial aid already covered their tuition.) Then, in 2022, Tennessee added emergency subsidies for books and other living expenses for needy students – up to $1,000 per student. Supplemental aid for low-income students is funded through state appropriations and private fundraising. For students who are the first generation in their families to attend college, current graduation rates have jumped to 34 percent with that extra support, compared to 11 percent without it, the 10-year report said.

“Combining financial support with non-financial support – that mentoring support, coaching support – is really the sweet spot,” said Graham Thomas, chief community and government relations officer at tnAchieves. “It’s a game changer, and that’s often overlooked for the money part.”

Coaching is best done in person on campus. During COVID, Tennessee launched an online mentoring platform, but students didn’t engage with it. “We’ve learned our lesson that in-person conversation is the most valuable way to build relationships,” said Ben Sterling, Chief Content Officer at tnAchieves.

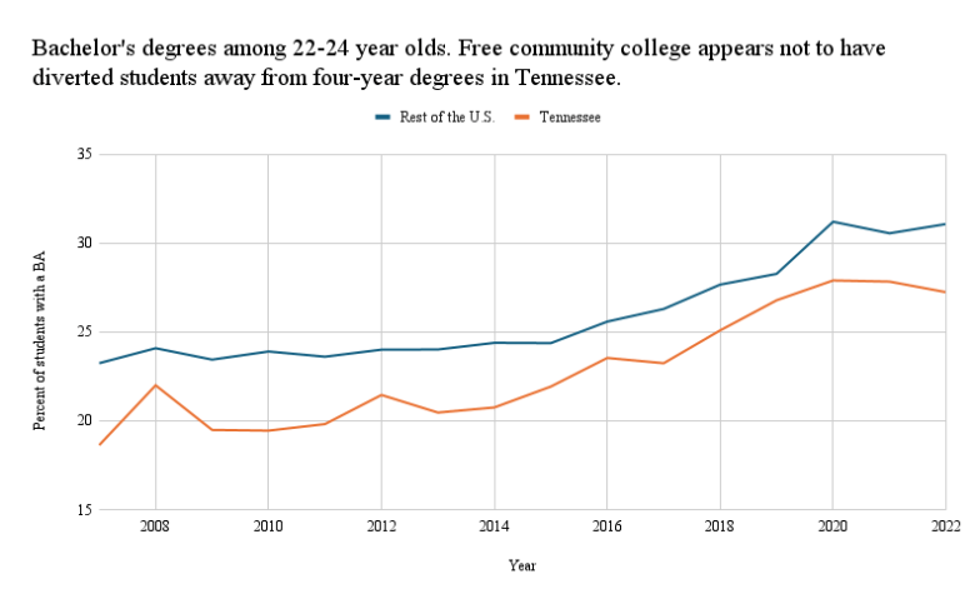

- The worst case scenario didn’t happen. When free community college was first announced, critics worried that the zero cost would lure students away from non-free four-year colleges. This is bad because the process of transferring from a community college back to a four-year school can be difficult, with students losing credits and time invested. Studies show that most students are more likely to complete a four-year degree if they start at a four-year institution. But the number of bachelor’s degrees did not drop. It seems possible that the tuition-free policy has lured students who in the past would not have gone to college at all without cannibalizing four-year colleges. However, Tennessee’s bachelor’s degree attainment, while increasing, remains far below the rest of the nation. (See graphic.)

As an aside, students can also use their Tennessee Promise scholarship funds at a limited number of community four-year colleges that offer associate degrees. About 10 percent of students in the program take advantage of this opportunity.

Despite all the positive signs for educational achievement in Tennessee, recent years have not been good. “Everything that happened with enrollment after COVID wiped out all the gains from the Tennessee Promise,” said Carathers of the University of Tennessee. A combination of pandemic disruptions, a strong job market and changing public attitudes about higher education have made it difficult to enroll in community colleges across the country. Students have begun to return to Tennessee, but community college enrollment is still below what it was in 2019.