November 27, 2024

4 read me

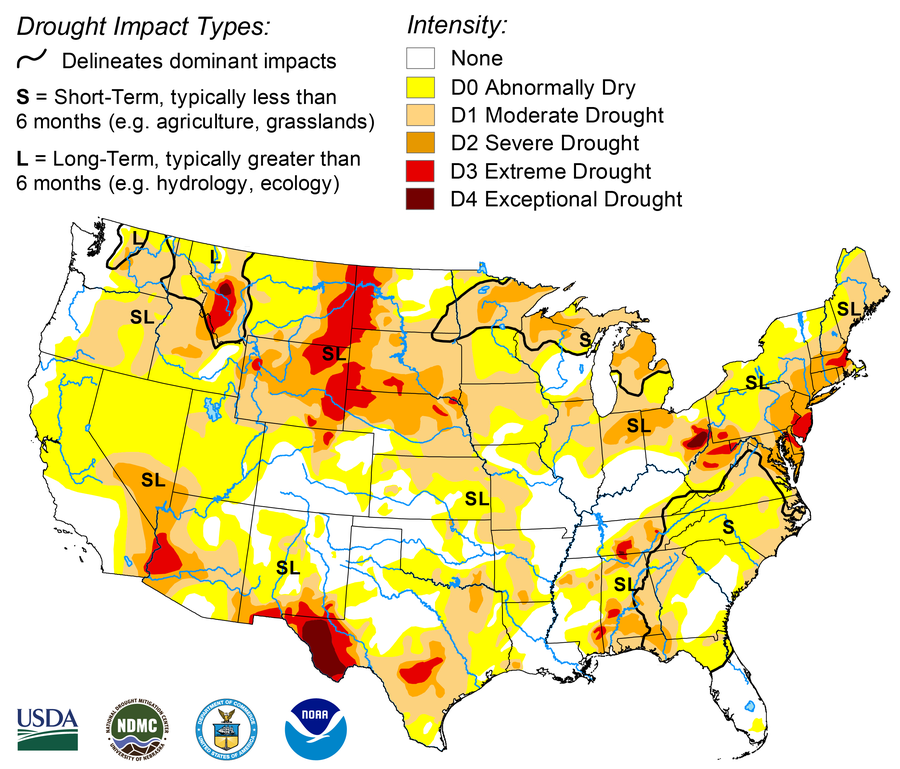

What Makes the Eastern US Drought Compared to the West?

Drought is more synonymous with the western US, but the eastern part of the country can quickly descend into such conditions.

New Jersey’s Manasquan Reservoir, which supplies drinking water to 1.2 million people, dropped below half empty in mid-November.

Lokman Vural Elibol/Anadolu via Getty Images

The water level is dropping in the reservoirs. multiple forest fires they’ve set the dry brush on fire, exposing the people of the region harmful level of air pollution. It has hardly rained in weeks.

This time we are not talking the often drought-stricken western US but usually wetter eastern the part of the country—where unusually severe drought it has caused water restrictions, damaged crops and fueled as many fires in six weeks as New Jersey normally sees in six months. Some of the effects resemble dry spells in the West, but drought in the East is a different beast.

The The two halves of the country have very different climates. Much of the West has distinct wet and dry seasons: rain and snow fall from late fall to early spring, and that’s mostly for the year. The snow on the high peaks of the western mountains is gradually melting in the spring and summer, when the streams are full and the vegetation properly watered, when everything is going well. But when winter precipitation is poor or a hot spring and summer causes rapid snowmelt, there is less to keep reservoirs full. Western states manage these resources to help them weather a dry year, but multiple years of failed rains and hot weather can lead to disastrous drought. This It happened in California a decade agowhen hot weather officially pushed more than half of the state into “exceptional” drought status, the highest category used. US Drought Monitor.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

A large part of the East coast, on the other hand, can see precipitation in every month of the year – and it usually does. Dry periods there “tend to be shorter in duration and not these big disasters in western North America,” says Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who studies drought.

The US Drought Monitor is produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map by NDMC.

But when there are weeks between rains, a drought can develop very quickly. This has been especially true this fall in the Northeast. After a very wet winter and spring, many areas there experienced six weeks of little or no rain and unusually warm temperatures. And warmer temperatures increase evaporation, drying out the soil and plants even faster. “It’s wild how far we’ve fallen” when it comes to water in the Northeast, says David Boutt, a hydrologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “All these lakes and streams seem to be feet lower than feet.”

Wells are running dry in Connecticut. Officials in Philadelphia are closely monitoring the Delaware River’s “salt front” — where freshwater from its river meets saltwater from the ocean — in case ocean water pushes further downstream and threatens drinking water supplies. New York City has issued its first drought warning in 22 years, urging residents to take several steps to voluntarily reduce water use. “It’s not something the Northeast usually deals with, so it’s exciting to read,” says Denise Gutzmer, a drought impact specialist with the National Drought Mitigation Center.

It could be worse. The record drought in southern New England occurred in the 1960s, after years of below-normal rainfall. If those conditions were to happen now, with all the population and infrastructure growth since then, “we’d be in a very bad situation,” Boutte says. “Most places would be out of water or almost hanging.”

Current dry conditions on the East Coast have also made fall wildfires much worse than usual; they are igniting more easily, and they are burning hotter and longer. “We’re used to having some reliable rain, and that helps put out our fires,” says Michael Gallagher, a research ecologist with the US Forest Service who studies the fires. This year, however, “fires are burning in increasingly atypical places,” including Prospect Park in the heart of Brooklyn, NY, and small green spaces in Manhattan.

One small thing that makes the drought worse is that it’s happening in the fall, when both humans and plants need less water and there’s generally less evaporation than in the heat of summer. But seasonality is also contributing to other factors that make fires worse: for example, Deciduous trees are shedding their leavesadding more potential fuel to any spark.

A series of storms brought some rain and snow to the region last week and this week, suppressing the fires and reducing the risk of more fires. But they will not end the drought; it will still take time for these rains to add enough to eliminate the current deficit. “We’re not one storm away from making everything better again,” says Gallagher. Boutt agrees, saying “the soils are so dry” that it will likely take 10 inches of rainfall, spread over the next few months, to bring water levels back to normal.

Exactly what the weather will bring for fall and winter is uncertain. Reliable weather forecasts extend about seven days into the future, while seasonal forecasts only provide a relative probability of the weather for the following months. In the Northeast today, the odds are for warmer than normal weather, but roughly the same chance of wetter or drier conditions.

Looking ahead, moreover, as the climate continues to change as temperatures rise, work by Boutt and others suggests that fluctuations between wet and dry periods in the Northeast are becoming more frequent, every two to four years.

During this time of year, the risk of wildfires should decrease at least slightly as the days get shorter and the nights get colder. “It doesn’t burn as well when it’s cold,” says Gallagher. This is especially true when nighttime frosts occur, as it takes time for the moisture in that frost to evaporate when the sun rises. Gallagher warns, however, that there have been large fires in the northeast in all seasons. If the dry and windy weather pattern continues, fire activity may resume.

And even with some rain and snow in the coming months and fire risk remaining low, there is a certain amount of “memory” in the water table, streams, rivers and lakes; they need time to recover, Boutte says. . “We will feel that in the spring and summer,” he added.