Since the first outbreak of bird flu hit the U.S. earlier this year, health and agriculture experts have been doing just that struggling to keep up The virus’ route is erratic as it spreads through dairy herds and an unknown number of humans. The risk of infection still seems low for most people, but dairy workers and others directly exposed to the cows they have become ill. from canada the first human case it was reported, in a teenager there critical situation. To better manage the troubling situation, scientists are picking up a pathogen-hunting tool that has proven powerful in the past: wastewater surveillance.

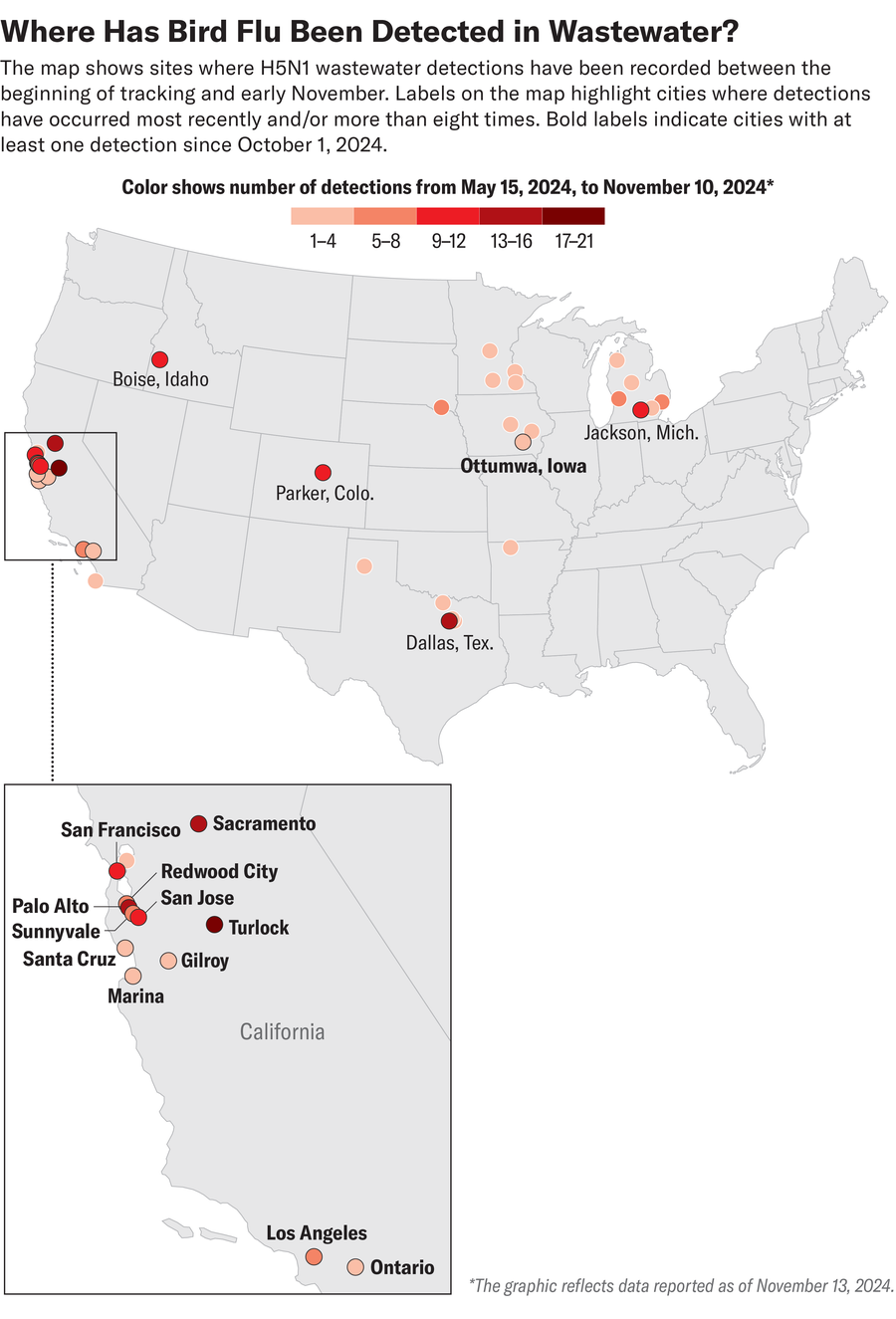

Over the past two weeks, wastewater samples from several locations mostly scattered across California have tested positive for the genetic material of the bird flu virus, H5N1, including the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento and San Jose. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Wastewater Surveillance System Detections were reported at 14 sites In California, the collection period ended on November 2. As of November 13, across the US, 15 sites monitored by WastewaterSCAN, a project led by researchers at Stanford University and Emory University, reported positive samples this month. But finding H5N1 material in wastewater doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a risk to human health, says civil and environmental engineer Alexandria Boehm, co-director of WastewaterSCAN at Stanford University.

Analyzing trace amounts of viral genetic material, which is often flushed into sewers through feces, can alert scientists and public health experts to possible increases in community infections. It became wastewater sampling A tool for predicting COVID cases Across the US, for example. But the way H5N1 affects both animal and human populations makes it difficult to identify sources and understand disease risk. It could be H5N1 fatal in birds. Cows usually recover from symptoms—such as fever, dehydration, and reduced milk production—but they are veterinarians and farmers. reporting that cows are being slaughtered at a higher rate In California than in other affected states. Cats that drink raw milk from infected cows can develop it fatal neurological symptoms. Current human cases have not resulted in any known deaths (most people have flu-like symptoms, although some develop eye infections), but past large outbreaks have been outside the US. caused deaths.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribing. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

American scientific He spoke with Boehm about the detection of avian flu in wastewater and the ways scientists are using it to better track and understand disease prevalence and exposure in animals and humans.

(Following is an edited transcript of the interview.)

When did WastewaterSCAN start tracking H5N1?

We noticed something very unusual in Amarillo, Texas (spring 2024), after the flu season, we saw very high levels of influenza A (a type of influenza virus that infects humans) RNA nucleic acids in their wastewater. It was surprising because we know of influenza A with cases in the community in sewage lines, but there were not many cases in the community, and it was after the flu season. Then we also heard on the news that cattle infected with bird flu had been found in the same area of Texas. So we collaborated with local wastewater treatment plants and public health officials to test the wastewater. And we find that it was, in fact, H5 (a subtype of avian influenza A virus) in their waste stream. We determined that most of this H5 came from legal discharges into sanitary sewers from milk processing plants.

Then, when we scaled up the H5 trial across the country, soon after that we were finding places where cows were infected (with the virus). In June, the CDC sent out notices urging states to try to measure H5 in wastewater, noting that the measurement could help understand the extent and duration of the U.S. outbreak.

Has the wastewater analysis been able to trace the cases to any source?

We can’t always rule out wild birds or poultry or humans, but overall the preponderance of evidence suggests that most inputs come from cow’s milk. That cow’s milk is making its way into consumers’ homes, where people flush it down the drain. I’m sure you spilled milk down your sink, I know. It also comes from licensed operations, where people are making cheese or yogurt or ice cream, and starting with a dairy product that contains avian flu nucleic acids.

I want to point out that it is the milk in the homes of people who may have avian flu RNA no infectious or threats to human health. It’s just a marker that some milk entered the food chain that originally contained the virus. It is killed because they are dairy pasteurized—and that’s why, by the way, drinking raw milk or something eating raw cheese not really recommended right now. The RNA that makes up the genome of these viruses is very stable in wastewater. It is stable even after pasteurization. So you pasteurize raw milk, and the RNA is still in the same concentrations.

Detection in waste water does not mean that there is a risk to human health. This means that there are still infected animals around, and work is still needed to identify these animals and remove their products from the food chain, which is the goal of the officials in charge. appearance aspect.

How might we better determine where genetic material comes from and assess human infection rates?

It is very difficult because genetically the virus is not different (between sources). It’s not like we can say, “Oh, what’s in humans is going to be like that, so let’s look for it.” We are working very closely with public health departments who are really proactive in sequencing positive flu cases. If we start seeing it in more people, we’ll probably recognize it because we’ll see differences in the wastewater.

I don’t want to be alarmist, because right now the risk of H5N1 is very low, and the symptoms are very mild. But I think the worry is that the virus may mutate this flu season. Even someone who is infected with (seasonal flu) can become infected with H5N1, and maybe they might create a new strain that can be more serious. We hope that wastewater data, along with all the other data that people and agencies are collecting, will help us figure out what’s going on and better protect public health.

What trends are you seeing in your care right now?

Lately, California has been on fire. Many California wastewater samples are coming back as positive, even in highly urban areas such as the Bay Area and Los Angeles. The question is: Why? Some of these locations actually have small operations where people are making dairy products. But another explanation, as I mentioned earlier, is simply the waste of dairy products.

How do wastewater H5N1 levels relate to animal infections?

We are seeing it as an early or simultaneous indicator of cattle in areas infected with bird flu. The first detections were in Texas, and we saw it many detections in Michigan a little while, and now the hot spot is California. As scientists, we will study all this in the future. But anecdotally, H5 detections in wastewater are continuing when flocks are identified, and then once it’s under control, we stop seeing it.

Public health officials are using the data to say, “OK, we got a positive at this location. What are the different sources that could be causing this? Have we tested all the cattle that bring dairy products to the industries in this sewer line? Have we removed all the infected herds in our state?” we have, because now we don’t get anything positive in the waste water?’

How else are scientists and officials staying on top of the cases and spreading the word?

(US Department of Agriculture) and different entities in the country they follow from the point of view of animal health and food safety. Therefore, tests are carried out on cow herds and dairy products. Birds are also tested, followed by workers in contact with infected flocks and infected birds. On the clinical side, there’s a push to sequence flu-positive samples to understand what type of flu it is, as a sort of safety net to see if there’s avian flu circulating among people. So far, the cases have been in people exposed to infected animals, working in farms and possibly in some of their family members.

How has H5N1 tracked compared to COVID or other pathogens?

All other pathogens we track have been conceptually similar to COVID, where humans are the source (of pathogenic material in wastewater). We know that the appearance of viral or fungal material in wastewater is consistent with cases. Avian flu is the first example where we’re using wastewater to track something that’s primarily, at least for now, not of human origin, but has potential impacts on human health for a variety of reasons. It’s been really awesome to study how wastewater can be used to track human disease, as well as zoonotic pathogens—pathogens that affect animals. So now we are thinking about what the waste water can be used for. What other types of animal by-products end up in the waste stream that may contain infectious disease biomarkers? The H5 is our first example, and I’m sure there will be more.