December 19, 2024

4 read me

Trump’s pick for NIH director could harm science and people’s health

With a possible outbreak of bird flu, Donald Trump’s appointment of Jay Bhattacharya, a scientist critical of COVID policies, for the NIH is the wrong move for science and public health.

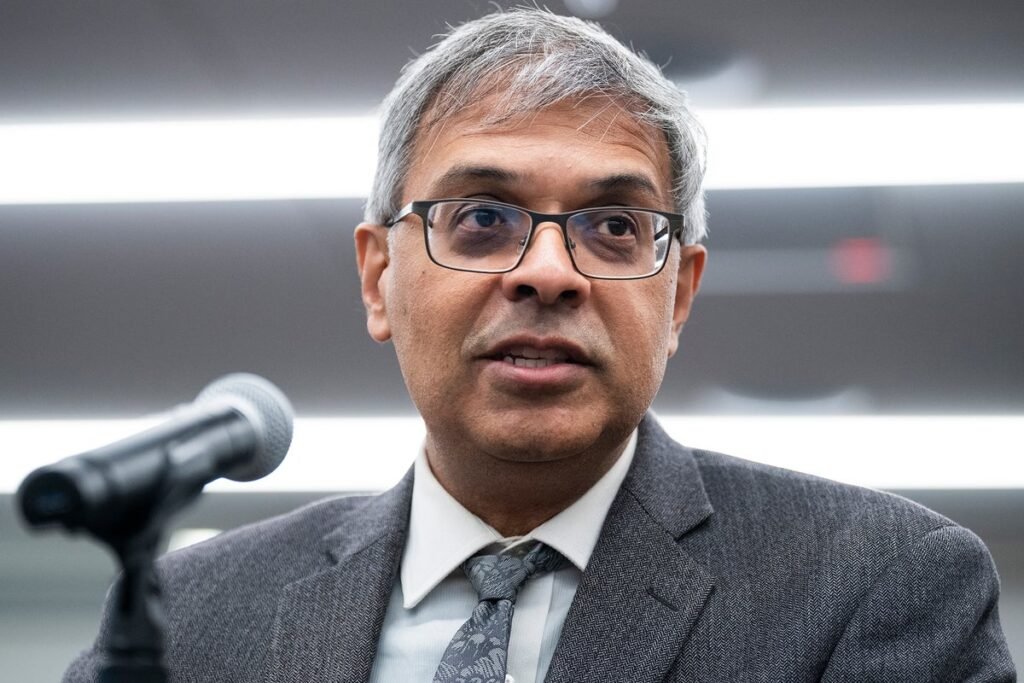

Jay Bhattacharya speaks during a panel discussion with members of the House Freedom Caucus on the COVID-19 pandemic at The Heritage Foundation on Thursday, November 10, 2022.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

President-elect Donald Trump wants Stanford University medical scientist and economist Jay Bhattacharya to lead the National Institutes of Health. NIH is a global science powerhouse. Its mission is “to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and to apply that knowledge to improve health, extend life, and reduce disease and disability.”

Most politicians, even when they criticize the agency, acknowledge the good it has done in building effective public health measures. Cancer death rates continue to decline, for example, because of the work of NIH researchers on prevention, detection and treatment.

Bhattacharya doesn’t see the agency’s successes that way. On his podcast From the Science FringeBhattacharya recently he said he is amazed “in accordance with the authoritarian trends of public health.” A similar issue was addressed by a Newsmax interview: “(We need to) transform the NIH from something (used) to control society into something that aims to discover the truth to improve the health of Americans.”

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

Scientists who apply for NIH funding, sit on peer review panels, and administer grants would be surprised to hear that society controls them. They do science. Claims of authoritarianism are a screen for pushing a particular agenda that could harm NIH. Bhattacharya’s science agenda is political: pitting concerns for personal autonomy against evidence-based public health science. This is not good for NIH leadership.

Bhattacharya has never explained how the NIH controls society, given its role as a research organization, and it is hard to see how it does, except perhaps by setting research priorities and awarding funding based on peer review. Against public health legislation that has controlled lead emissions in vehicles, enforced vaccination requirements for children in public schools, and promoted folate fortification in breads? fluoride in drinking water? This legislation has improved population health in terms of cognitive performance, infectious disease burden, neural tube defects in pregnancy, and oral health, respectively. Is this the kind of control he fears?

Public health authorities decide on a science-based health promotion measure for a population, often vulnerable and unaware of health risks, when the health benefits are clear. NIH research provides evidence for these public health measures. It is fair to debate the quality of scientific evidence and the benefit to population health compared to restrictions on autonomy and choice, but establishing risk mechanisms for population health and making recommendations based on that evidence is not authoritarianism, and making such a comparison is not the way to go. to do good science or build confidence.

Bhattacharya’s views are an unfortunate legacy of the COVID pandemic, when he argued against alleged public health abuses. Barrington Grand Declaration Back in 2020. The statement said that isolating only the people at highest risk and allowing the spread of COVID among the healthier would build herd immunity without increasing the mortality from COVID. In response, public health officials and NIH leaders criticized Bhattacharya based on the science: In a setting of asymptomatic viral transmission, high infectivity, and inevitable population mixing, such a “targeted protection” strategy was unlikely to protect vulnerable populations. Bhattacharya called this censorship and tried to persuade him without success Supreme Court to weigh against social media sites that removed his posts.

This personal pique is a distraction and should not obscure the central focus of US public health policy during the pandemic. Science supported school closings, work-from-home policies, major restrictions on gathering in public spaces, and face mask requirements as effective ways to reduce hospital admissions and buy time to develop vaccines. You can challenge science, as many have; but it is not authoritative to use science for politics. Likewise, they may value personal autonomy and oppose vaccination or face mask mandates, but using scientific evidence to support these measures does not mean that scientists have “engaged in censorship, data manipulation, and disinformation,” Trump falsely claimed to justify his candidates. .

Authoritarianism in science or public health was not responsible for the pandemic’s heavy toll on the US. Structural factors such as income inequality and access to health care were the main drivers of COVID mortality. As the NIH director prepares the country for the next pandemic, it would be much more effective to invest in pandemic preparedness and infectious disease research and, in addition, ensure that everyone has access to health care.

Indeed, proposed remedies to make science less authoritarian, such as shifting NIH grants to states in the form of “block” grants (recommended by conservative policy agendas). 2025 project), will not promote “non-authoritarian” public health, but will almost certainly degrade the quality of American science. Will states be able to match the NIH peer review system, which is considered the world’s model for transparent, confidential, and impartial evaluation based on merit and scientific consensus? It is hard to imagine how a decentralized state-level effort would result in fairer review or more impactful science. Will scientists in some states be barred from funding research into family planning or women’s health, for example?

We do not know what other policies Bhattacharya may propose. Viral Banning gain-of-function research? Eliminating research involving fetal tissue and limiting studies using animal models? Change in financing away from infectious diseases investigation, as RFK, Jr., suggested Trump’s choice to lead the Department of Health and Human Services? Giving peer review panels less influence in determining scientific merit?

The best way to “depoliticize science,” if that’s your concern, is to get out of the way and let scientific research drive research and let peer review determine priority for funding. “Authoritarianism” against Bhattacharya is nothing more than the application of science to improve the health of the population. Pitting personal autonomy against the application of science policy is fine for webcasts and think tanks to make trivia, but inappropriate for NIH leadership. If the pandemic wants to focus on promoting personal autonomy in politics, it may be appointing itself to the wrong agency. Bhattacharya is not what the NIH needs.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily their own. American scientific