Lifesaving methods of HIV treatment. Medicines for hepatitis C. New treatment regimens for tuberculosis and the RSV vaccine.

These and other major medical breakthroughs are happening in large part thanks to a major arm of the National Institutes of Health, the largest funder of biomedical research on the planet.

For decades, researchers funded by the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have been quietly at work in red and blue states across the country, conducting experiments, developing treatments and conducting clinical trials. With its $6.5 billion budget, NIAID has played an important role in the discoveries that have kept the nation at the forefront of infectious disease research and saved millions of lives.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic.

NIAID helped lead the federal response, and its director, Dr. Anthony Fauci, drew fire amid nationwide school closures and recommendations to wear face masks. Lawmakers were outraged when they learned the agency had funded an institute in China that was involved in controversial research into bioengineering viruses, and questioned whether there was enough oversight. Republicans in Congress have held numerous hearings and investigations into NIAID’s work, slashed NIH’s budget, and proposed a comprehensive overhaul of the agency.

More recently, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Trump’s nominee to head the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIH, has said he wants to fire and replace 600 of the agency’s 20,000 employees and shift research away from infectious diseases and vaccines. , which are at the heart of NIAID’s mission to understand, treat, and prevent infectious, immunological, and allergic diseases. He said this half of the NIH budget should focus on “preventive, alternative and holistic approaches to health”. He is particularly interested in improving diet.

Even NIH’s staunchest defenders agree that the agency could benefit from reform. Some would like to see fewer institutes, while others believe there should be term limits for directors. The important debate is over whether to fund and how to control controversial research methodsand concern with the way agency managed transparency. Scholars inside and outside the institute agree that work needs to be done to restore public confidence in the agency.

But experts and patient advocates worry that overhauling or dismantling NIAID without a clear understanding of the important work being done there could jeopardize not only the development of future lifesaving treatments, but the nation’s place at the helm of biomedical innovation.

Good journalism matters:

Our nonprofit, independent newsroom has one mission: to hold powerful people accountable. This is how our investigations are progressing driving real-world change:

We are trying something new. Was it helpful?

“The importance of NIAID cannot be overstated,” said Greg Millett, vice president and director of public policy at amfAR, a nonprofit organization dedicated to AIDS research and advocacy. “The amount of knowledge, research, breakthroughs that NIAID has done is just incredible.”

To understand how NIAID works and what’s at stake with the new administration, ProPublica spoke with people who have worked at, received funding from, or served on boards or commissions that advise the institute.

Decisions, Decisions

The director of NIAID is appointed by the head of the NIH, subject to Senate approval. Directors have broad powers to decide what research to fund and where to award grants, although these decisions have traditionally been made on the basis of recommendations from external expert panels.

Fauci led NIAID for nearly 40 years. He has courted controversy in the past, particularly in the early years of the HIV epidemic, when community activists criticized him for initially excluding them from the research agenda. But overall, before the pandemic, he enjoyed relatively solid bipartisan support for his work, which included a strong emphasis on vaccine research and development. After his retirement in 2022, he was succeeded by Dr. Jeanne Marrazza, an HIV researcher who previously served as director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She spent a lot of time in the halls of Congress working to restore bipartisan support for the institution.

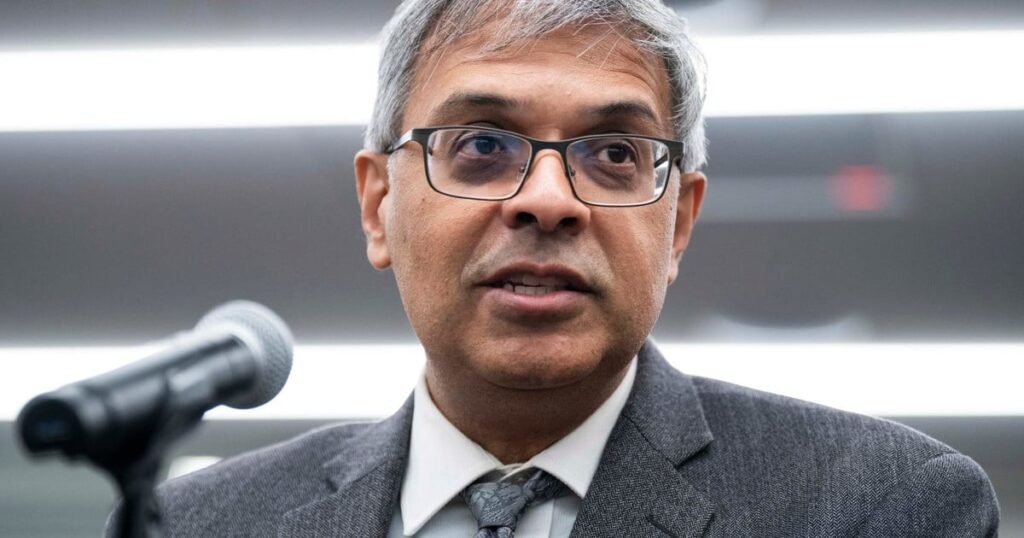

NIH directors typically span presidential administrations. But Donald Trump nominated Dr. Jay Bhattacharya to head the NIH, and the current director, Dr. Monica Bertagnoli, told staff this week that she will step down on Jan. 17. Bhattacharya, a professor at Stanford University, has devoted his career to studying health policy issues such as the implementation of the Affordable Care Act and the effectiveness of US funding for HIV treatment internationally. He also investigated the NIH, concluding that while the agency funds a lot of innovative or new research, it should be doing more.

In March 2020, Bhattacharya co-authored an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal arguing that the death toll from the pandemic was likely to be much lower than predicted and called for a review of the lockdown policy. In October of that year, he helped write a declaration which recommended lifting the COVID-19 restrictions for those “at minimal risk of death” until herd immunity is achieved. In an interview with the libertarian magazine The reason is in Junehe said he believed the COVID-19 outbreak most likely originated from a lab accident in China and that he could not consider Trump’s Operation Warp Speed, which led to the development and distribution of vaccines against COVID-19 at an unprecedented rate , as a general success because it was part of the same research program.

Bhattacharya declined ProPublica’s request for an interview about his priorities for the agency. Recent Wall Street Journal article said he is considering tying “academic freedom” on campuses to NIH grants, though it’s unclear how he would measure that or implement such a change. He also raised the idea of term limits for directors and said the pandemic “was simply a disaster for American health science and policy”, which is now in desperate need of reformation.

Where does the money go

NIAID grants go to nearly every state and more than half of congressional districts nationwide, supporting thousands of jobs across the country. Last year, nearly $5 billion of NIAID’s $6.5 billion budget went to U.S. organizations outside the institute, according to a ProPublica analysis. NIH reportonline database of your expenses.

In 2024, Duke University in North Carolina and Washington University in Missouri were the largest NIAID grantees, receiving more than $190 million and $173 million, respectively, to study HIV, West Nile vaccines, and biosecurity, among other things.

Over the past five years, $10.6 billion, or about 40% of NIAID’s budget for outside U.S. institutions, went to states that voted for Trump in the 2024 presidential election, the analysis shows. Studies show that every dollar spent by the NIH receives from 2.50 USD to 8 dollars in economic activity.

This money is the key to the development of medicine as well as a career in science. Most undergraduates and postdoctoral fellows rely on the funding and prestige of NIH grants to launch their careers.

New drugs and global impact

The NIH pays for most of the basic research on new drugs worldwide. The private sector relies on this public funding; researchers at Bentley University found that NIH money is being left behind every new pharmaceutical drug approved from 2010 to 2019.

This includes RSV therapies for children, vaccines for COVID-19, and treatments for Ebola, all of which have key patents based on NIAID-funded research.

NIAID research has also improved the treatment of chronic diseases. New understanding of inflammation from NIAID-funded research has led to cutting-edge drug research for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and growing evidence that viruses can have long-term effects, from multiple sclerosis to lingering COVID. When private companies turn this research into blockbuster drugs, the public benefits from new treatments as well as jobs and economic growth.

The weight of NIAID’s funding also allows it to play smaller roles that have been necessary to advance science and the United States’ role in biomedicine, several people said.

The institute brings together scientists who are usually competitors to share findings and tackle big research questions. Having such a neutral space is critical to advancing knowledge and ultimately spurring breakthroughs, said Matthew Rose of the Human Rights Campaign, who has served on several NIH advisory boards. “Academic organizations are very competitive with each other. If NIH brings grantees together, it will help make sure they are talking to each other and sharing research.”

NIAID also funds researchers internationally, ensuring that the US continues to have an influential voice in the global biosafety conversation.

NIH is also working to improve representation in clinical trials. Straight, white men still is over-represented in clinical research, leading to underdiagnosis of women and all people of color, as well as members of the LGBTQ+ community. As an example, Rose pointed to the long history of no signs of heart disease in women. “These are the things that for-profit companies are not interested in,” he said, noting that the NIH helps set the agenda for these issues.

Nancy Sullivan, a former NIAID senior investigator, said NIAID’s strength lies in its ability to invest in a broad understanding of human health. “It’s basic research that allows us to develop treatments,” she said. “You never know what part of basic research is going to be the basis for treating a disease or defining a disease so you know how to treat it,” she said.

Sullivan should know: It was her work at NIAID four years ago that led to the first approved treatment for Ebola.