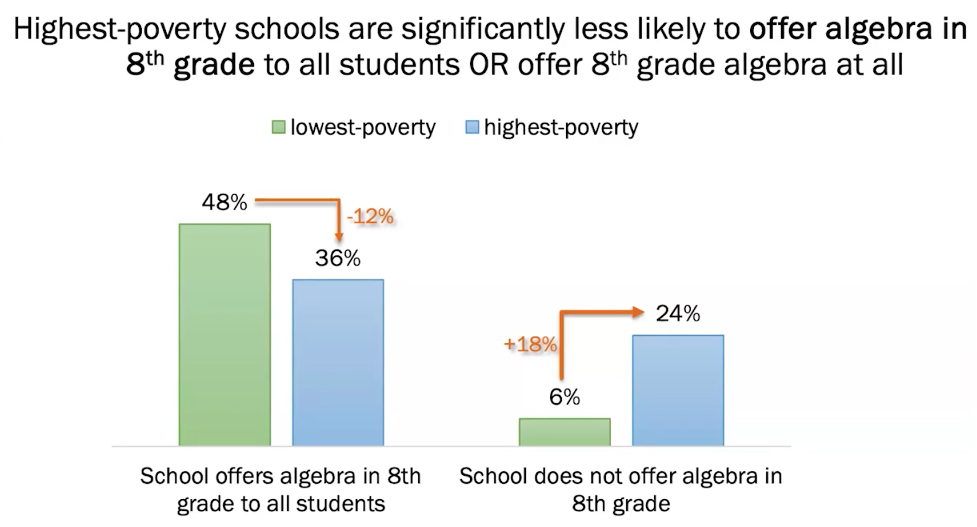

Conversely, poor schools are much less likely to adopt an algebra-for-all policy for eighth graders. Almost half of the wealthiest schools offered algebra to all their eighth-grade students, compared with about a third of the poorest schools.

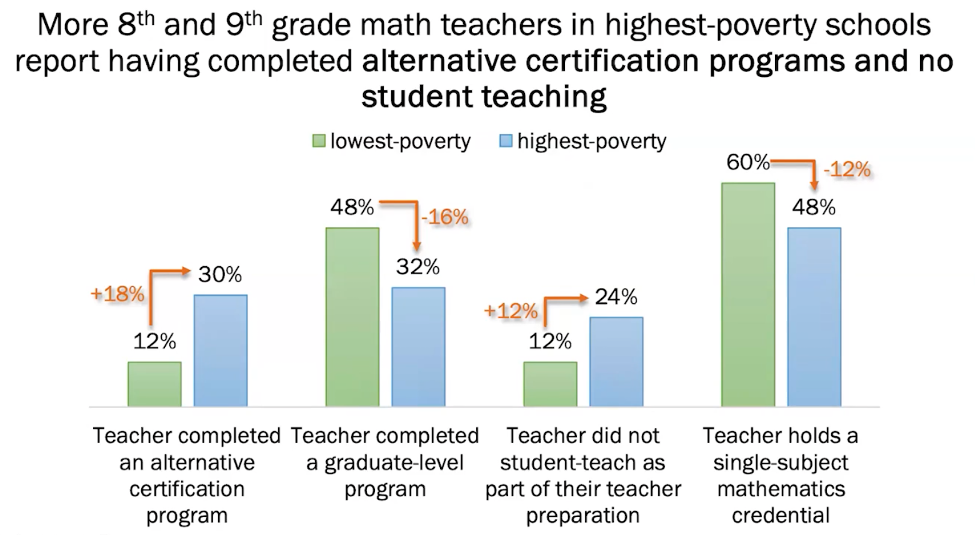

Mathematics teachers in poor schools tend to have less professional training. They are much more likely to have entered the profession without first earning a traditional college or university degree, rather than completing an alternative on-the-job certification program, often without student teaching supervision. And they are less likely to have a college degree or hold a degree in mathematics.

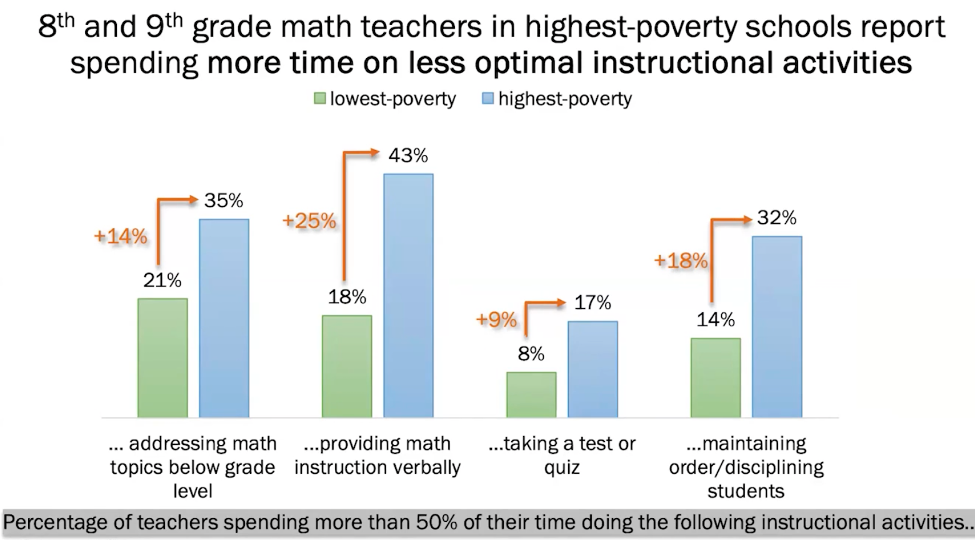

In surveys, one-third of math teachers in high-poverty schools report spending more than half of their class time teaching subjects that are below grade level, as well as managing student behavior and disciplining students. Lecture-style teaching, as opposed to classroom discussion, was much more common in the poorest schools than in the wealthiest schools. RAND researchers also found similar disparities in instructional patterns when they examined schools by race and ethnicity, with black and Latino students receiving “less optimal” instruction than white students. But these disparities are stronger by income than by race, suggesting that poverty may be a bigger factor than bias.

Many communities tried to put more eighth graders in algebra classes, but that sometimes put unprepared students at a disadvantage. “Just giving them an eighth-grade algebra course is not a magic bullet,” said AIR’s Goldhaber, who commented on the RAND analysis during a Nov. 5 webinars. Either the material is too difficult and students are failing, or the course was “algebra” in name only and didn’t really cover the content. And without a college prep path of advanced math classes to take after algebra, the benefits of taking Algebra 1 in eighth grade are unlikely to accrue.

It is also not economically practical for many low-income middle schools to offer an Algebra 1 course when only a handful of students are advanced enough to take it. A teacher would need to be hired for even a few students, and those resources could be spent more efficiently on something else that would benefit more students. This puts the most advanced students in low-income schools at a particular disadvantage. “It’s a tough problem for schools to tackle alone,” Goldhaber said.

Improving the quality of math teachers in the poorest schools is a critical first step. Some researchers suggest paying strong math teachers more to work in high-poverty schools, but that would also require renegotiating union contracts in many cities. And even with financial incentives, there is a shortage of math teachers.

For AIR’s students, Goldhaber argues that the time for math intervention is in elementary school to ensure more low-income students have strong basic math skills. “Do it before middle school,” Goldhaber said. “For many students, middle school is too late.”

This story about eighth grade math was written by Jill Barshey and produced by The Hechinger Reportan independent, nonprofit news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Evidence points and others Hechinger Bulletins.