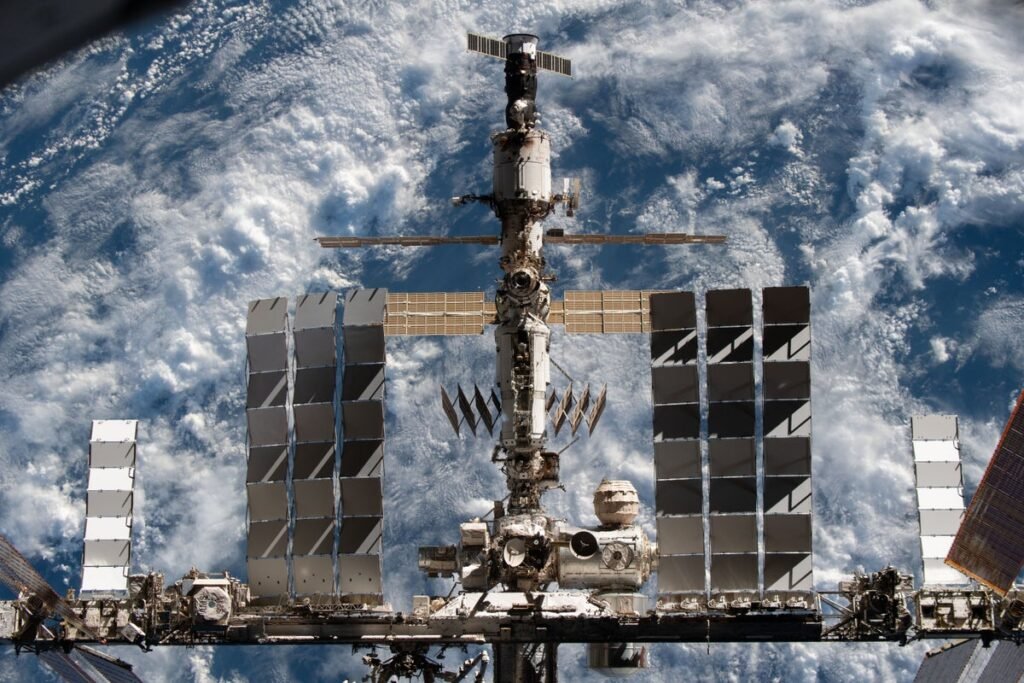

In hostile conditions outside Earth, a spaceship is all that stands between an astronaut and certain death. So having years of seemingly unfixable leaks on the International Space Station (ISS) seems like a nightmare scenario. It’s also a reality, what a recent agency report called “a top security risk.” Among the headlines of the months Astronauts captured by Boeing’s Starliner vehicle and NASA announced a contract with Elon Musk SpaceX to destroy the ISS At the start of the next decade, ongoing concerns about leaks are a reminder that supporting a long-term population in space is an out-of-this-world challenge.

At the same time, leaks from the station are a daily occurrence, perhaps surprising to those of us who are neither engineers nor astronauts. “When you’re on the space station, it’s like your life here,” says Sandra Magnus, an engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology and a former NASA astronaut who previously served on NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Board, an independent panel that oversees safety. worries “You don’t run around in your everyday life and wonder if you’re going to make it He was hit by a car while crossing the streetright? It’s your life, you just live your life.

The amazing truth is that the ISS leaks some air every day, and always has. “All spacecraft escape,” says David Klaus, a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder. The space station is simply the most famous spacecraft in existence, and now it’s leaking more than ever.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

It’s actually leaking more, but not as much yet, says Michael Kezirian, associate professor of astronautical engineering at the University of Southern California. The current spill “is bigger than a hole, maybe two holes,” he says. “You’re talking about something rather small.” The worst publicly shared emission rate dates back to April, when the station was losing 3.7 pounds per day to the atmosphere. (For context, all the air above any square inch of Earth’s surface at sea level that extends to the bottom of the atmosphere weighs an average of 15 pounds.)

It’s also no surprise to experts that NASA and the international partners running the space station have had so much trouble investigating and fixing the leaks. “Leaks are hard to fix,” says Magnus. “The station is huge; there is a large volume of air. So trying to isolate a tiny little leak or anything that doesn’t leak a lot is difficult.” (Much of the station’s hull is also difficult to get inside, due to the sheer amount of equipment, cargo, and in general. things shuffles its corridors.)

Don’t panic—yet

The first leak problems, detected in September 2019, were found in a tunnel on Russia’s Zvezda service module, which was launched in July 2000. The tunnel connects a docking port to the main body of the module and the rest. space station Magnus describes the tunnel as a “back door,” primarily used to store trash slated for incineration in Earth’s atmosphere.

Astronauts have had some luck over the years finding the exact spots where the station is losing air and have even tried patching the tunnel. In theory, spacecraft leaks are easy to seal from the inside. “All you have to do is put something up against that leak with some kind of adhesive, and it self-seals against the leak,” says Klaus. “Spacecraft pressure helps hold the seal against leakage.” But those patchwork efforts have only reduced the flow of emissions, rather than eliminating them entirely.

While astronauts and ground control continue to troubleshoot, NASA and its Russian counterpart, Roscosmos, have decided to keep the leaky tunnel door closed whenever possible. It’s a basic solution, but a reasonable one, says Magnus, given the relatively small importance of the back porch. As long as leaks persist, Klaus says, the only real problem is that astronauts need more frequent or larger airdrops, which are one of the so-called consumables that cargo vehicles supply, such as food and water. the station

In the long term, if the leaks worsen, the shutdown strategy could be sustainable without serious consequences, the three experts say. Losing access to the port at the end of the tunnel would be inconvenient, requiring closer coordination between crews orbiting the lab and cargo vehicles and delivering material. “The logistics community will have to sharpen their pencils and figure out how to compensate,” Magnus says of this scenario. “Will it be a disaster? no Will it be a bit more challenging? Maybe.”

That approach also comes with its own complications: According to a September report, NASA and Roscosmos disagree on the threshold at which leaks will be severe enough to necessitate a permanent shutdown.

However, the leaks themselves, while far from ideal, are essentially under control. “No one should panic,” says Magnus. “It’s a serious problem, and they’re taking it seriously, that’s really the bottom line.”

wear and tear

The leak, however, is a reminder of just how long the ISS has spent in orbit. The oldest segments launched in 1998; since then they have been subjected to various stresses. Spaceships arrive and depart, rockets propel the ever-sinking laboratory above Earth, and materials are degraded by cosmic radiation. And the sun’s heat goes 16 times each day and goes 16 times as the station descends over the Earth’s day and night, and its components expand and shrink each time.

Sooner or later—hopefully later—all that mechanical stress will manifest itself in something more serious than stress leakage. “We know the space station can’t stay up there forever,” Kezirian says. “It’s a little easier with an old house to paint and replace the components that fail.” Home repairs in a space front post are more expensive and fixed, and at some point, entropy will win.

NASA hopes that won’t happen this decade and aims to keep the space station operational until the 2030s. (Russia has so far only committed to the orbiting lab until 2028). But the challenges of leaks add more urgency to a concern the Aerospace Safety Advisory has. He has been raising the bar for years: that the orbital laboratory will fail before it is safely destroyed—and will fall uncontrolled into the Earth’s atmosphere, its debris can cause serious damage to people and buildings. NASA commissioned SpaceX earlier this year Develop a vehicle to deorbit safely space station in 2031, aiming for a 2029 launch. It’s a very tight timeline for a program of this scale, so the anxiety remains.

A second clockwork hangs over the agency: In whatever scenario the space station meets its fiery doom, it will leave the US without a viable long-term orbital habitat. NASA officials have been promoting for years that companies will take over low-Earth orbit, launching and maintaining space stations, to continue the 24-year streak of continuous human occupation of the ISS.

Abandon Orbit again?

In 2020, the agency hired Texas-based Axiom Space to build the station’s first commercially built habitable module, which the company plans to launch in 2026 and then free-fly when the space station retires. In 2021, NASA also provided funding to companies including Washington State’s Blue Origin (owned by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos) and Texas-based Nanoracks to develop additional commercial targets in space. NASA says Axiom’s module is under construction and Blue Origin’s station components have been tested, but progress remains slow. Company representatives for each station contacted for this article declined to provide additional details about the current situation American scientific. Meanwhile, Axiom seems to be fighting back serious economic problems.

These proposed commercial stations may be able to learn from the ISS’s escape problems, Klaus says. “Once you’ve identified that as a potential concern, you can be smarter about future designs,” he says. “If you’re smart, you don’t make the same mistakes twice. It happens once; you fix it and move on.”

But fears are growing that those stations will not be operational by the time the ISS is retired or becomes uninhabitable, leaving the US only able to make short trips into Earth orbit.

For NASA, the prospect bears an uncomfortable resemblance to the retirement of the space shuttle fleet in 2011 without an active replacement. Nearly a decade later, the agency bought its own astronauts’ seats on Russian spacecraft to reach the ISS — an expensive strategy in a financial sense but also in terms of lost knowledge and expertise in the US space industry.

“You really don’t want that thing to happen again,” says Magnus. “If we are going to be a nation that explores space, then we have to do it in a smart, profitable and maximal way. (An approach) fit and boot is suboptimal, and wasteful.