The lawsuit challenging the EdChoice voucher program was filed by a coalition of more than 130 school districts across the state and is scheduled to go to trial next year.

William Phyllis began teaching in 1958. “I always liked the idea of schooling. I always liked the idea of a public school system,” Phyllis said. Just five years ago, Ohioans passed a constitutional amendment creating a Board of Education, and school education in the state was rapidly changing. “The state has started to make progress in terms of curriculum and programs for children,” he said. “At that point, there was no calling, no charter schools, no vouchers.”

School vouchers are government funds that help parents pay for private school tuition — ostensibly to give children in low-performing public schools the opportunity to attend a private school that participates in the program. The first major voucher programs were introduced in the 1990s. “Only a certain portion of the state’s general fund revenue will go to education,” Phyllis said. “So for every dollar that school districts take away and give to charters and vouchers, that’s a dollar less that goes to public education.”

Cleveland Scholarship Program was started in 1996, allowing Cleveland parents to use public money to pay for private school tuition, while also allowing students to attend schools in neighboring districts. The Education Choice Scholarship expanded the program in 2005. Last year, House Bill 33 revised the EdChoice program to include all students, regardless of school district performance or family income. Ohio now spends over $970 million for private school voucher scholarships.

According to Phyllis, who is now executive director of the Ohio Coalition for Equity and Adequate School Funding, the expansion of the voucher program has hurt public schools.

Hurt Ohio Vouchersa coalition of more than 130 school districts across the state filed a lawsuit in January 2022 challenging EdChoice as unconstitutional. “The EdChoice scholarship program poses a threat to the existence of the Ohio public school system,” the lawsuit states. “Not only does this voucher program unconstitutionally usurp Ohio’s public tax dollars to subsidize private school tuition, but it does so by depleting Ohio fund funding — the pool of money from which the state funds Ohio’s public schools — otherwise available to school districts, who are already experiencing difficulties. education of their students”.

One of the main arguments of proponents of voucher programs is that they help low-income families get a better education than they could get in public schools. But the data shows that most of the students who took advantage of EdChoice and the expansion came from wealthy families who already attended private school. For example, Montgomery, Miami, Greene, Warren, Butler and Clark counties saw a 313 percent increase in the use of EdChoice vouchers. Dayton Daily News reporter Eileen McClory, but enrollment at schools that accept vouchers rose only 3.7 percent. “More and more vouchers” are “being issued to students who have already attended private schools,” according to theReport for 2023 by the Ohio Institute for Education Policy. “In FY 2019, only 7% of new EdChoice voucher recipients had attended a private school the year before, but in FY23, nearly 55% of new voucher recipients had already attended private schools.”

“In my area more than 90 percent of students who used vouchers years ago never set foot in one of our public schools,” said Dan Heinz, a member of the Cleveland Heights-University Heights Board of Education and a supporter of the Vouchers Hurt Ohio lawsuit. “The whole notion that people used vouchers to avoid public schools was nonsense because the kids never went to school,” he said. “The only thing they avoided was tuition fees.”

Data from Art Ohio Department of Education and Workforce Resources shows that of the 1,817 students at Cleveland Heights University Heights who use EdChoice, 73.69 percent “do not qualify as low-income,” meaning their family income does not fall below 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. And a Cleveland.com report found that despite an increase in the number of students receiving Edchoice scholarships in the Cleveland area, those areas did not experience a significant drop in enrollment.

According to Heinz, the state left him and his colleagues no choice but to sue. “We were forced to do this by the Ohio legislature,” he said. “We tried everything else … we went to Columbus and testified at hearings. We hired lobbyists. And everything we’ve tried has been ignored by our extremely fraudulent legislature.” At one point, his district was losing $16 million a year on the voucher program. “That was 16 million of what we could put in front of students on our desks.”

Chad Aldis, vice president for Ohio policy at the Thomas Fordham Institute, a Koch-affiliated conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C., acknowledged that many EdChoice users already attend private schools, but said the program has provisions that which clearly benefit low-income families. Aldis also argues that due to changes in how Ohio schools are funded, the financial burden on schools is no longer a factor. Voucher funding comes directly from the state of Ohio without going through district budgets.” Now, when a student leaves the district, it’s much more like the student moves to Indiana, where the district can no longer claim the child, but that’s because they’re no longer educating the student.”

Many educators say the change didn’t make much of a difference, since public schools are still forced to rely on taxes and property taxes to make up for the lack of state support. “You could say it’s equally scary for every district in the state,” Heinz said.

Polly Taylor Gerken, a member of the Toledo Public School Board, spoke about her concerns about private schools excluding students from her community. “We’ve had kids who were expelled because private schools aren’t supposed to accept kids with disabilities,” Gerken said. “They can discriminate on the basis of race. They can discriminate on the basis of disability. They can discriminate based on family composition. So it’s not about choosing a school, because schools choose children.” Of the more than 40,000 students enrolled in EdChoice statewide in 2024, about 46 percent were white, and the EdChoice expansion is more than 82 percent.

popular

“Swipe to the bottom left to see more authors”Swipe →

Analysis from Art Cleveland plain dealer published in 2017 also found that 97 percent of voucher program money goes to religious schools. “The Ohio Catholic Conference has supported the expansion of EdChoice through advocacy with legislators and public testimony. Many parents also advocated directly with their representatives and senators for the EdChoice program,” wrote Michelle Duffy, associate director of communications for the organization. “Allowing more parents to choose Catholic education benefits families and their local communities.”

Religious institutions are playing a key role in school voucher campaigns across the country. “When vouchers came out in the 1990s, a lot of money really went to private religious schools,” said Christopher Lubienski, a professor of education policy at Indiana University in Bloomington. “In Cleveland, when the Supreme Court was looking at it, I think 97 percent of the vouchers were used in private religious schools,” he said. “You have a fairly significant transfer of money from the public treasury to private religious organizations.”

Originally scheduled for a decision by the Ohio Supreme Court this November, court a Franklin County judge has postponed the Vouchers Hurt Ohio trial until 2025. It is unclear what the outcome will be. Republicans won all three state Supreme Court elections in 2024, increasing their majority, even though the court had ruled EdChoice unconstitutional in previous years.

William Phyllis hopes Ohio government will start prioritizing what’s really important in education. “There are school districts that have had to cut art, music, physical education — a lot of programs from the state system because there’s no money to fund those programs. And it’s not that we don’t have enough money. It’s that a lot of money for public education is being siphoned out of the public school system and given to charters and vouchers.”

More from Nation

The city’s subway is home to—and unofficially sanctioned by the authorities—a strange institution unlike any other.

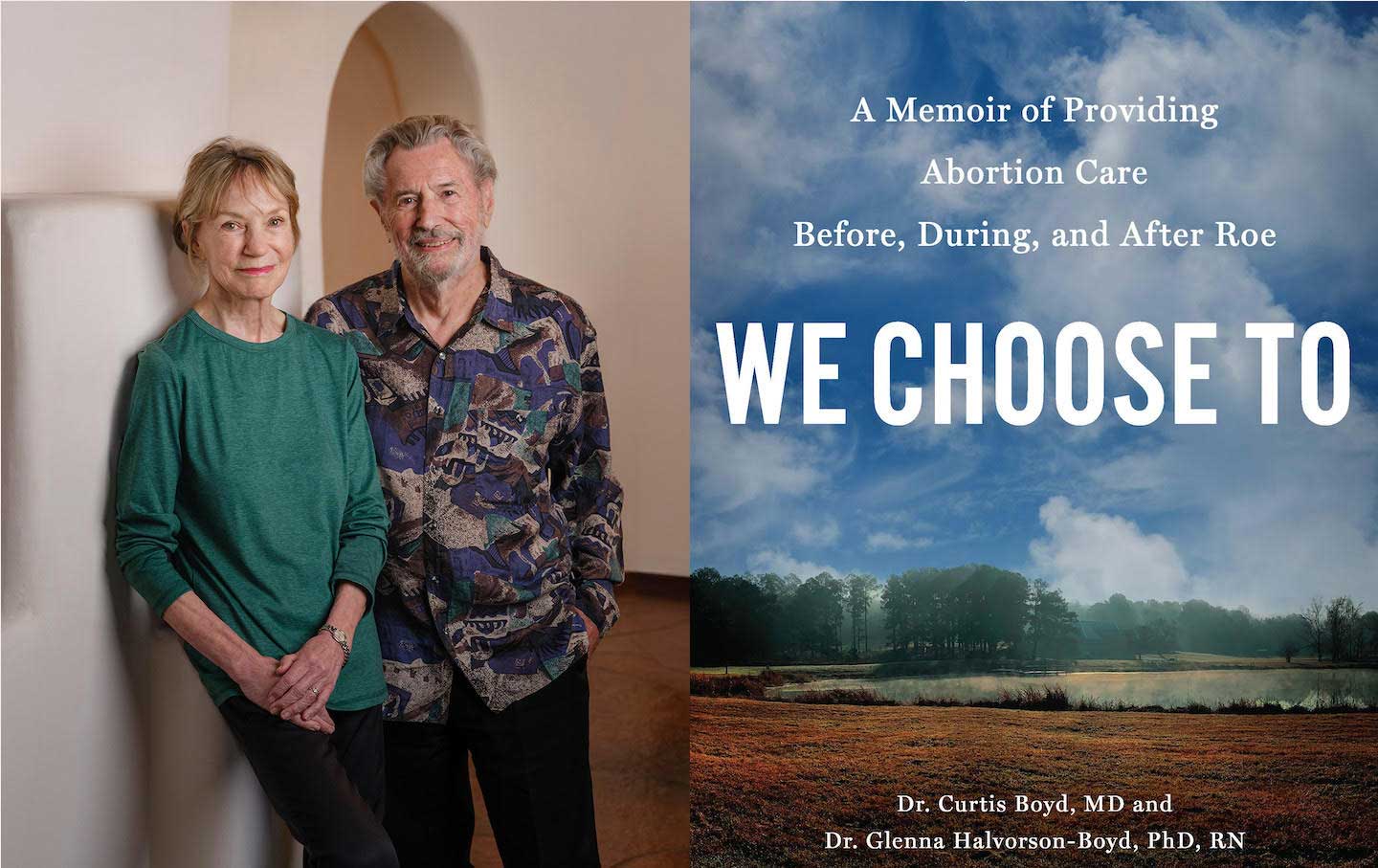

In their new book, We Choose, Dr. Curtis Boyd and Glenna Halvorson-Boyd reflect on the decades of helping women who needed abortions—before, during, and after Roe.

College programs designed to give students from underrepresented groups a foothold in careers are being reformulated or disappearing.

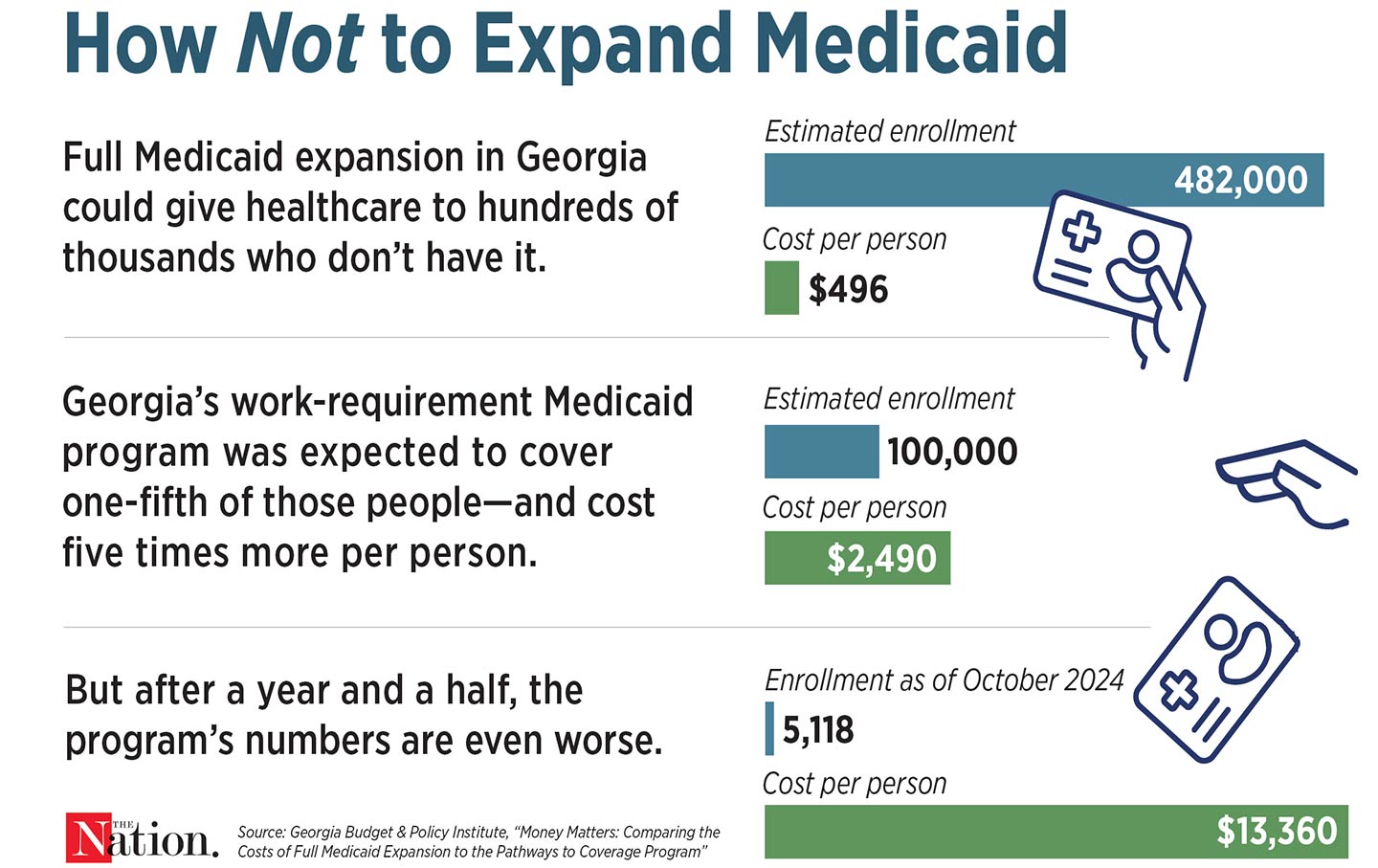

Georgia Republican Gov. Brian Kemp said 345,000 people would be enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program, which has strict work requirements — so far only 5,118.