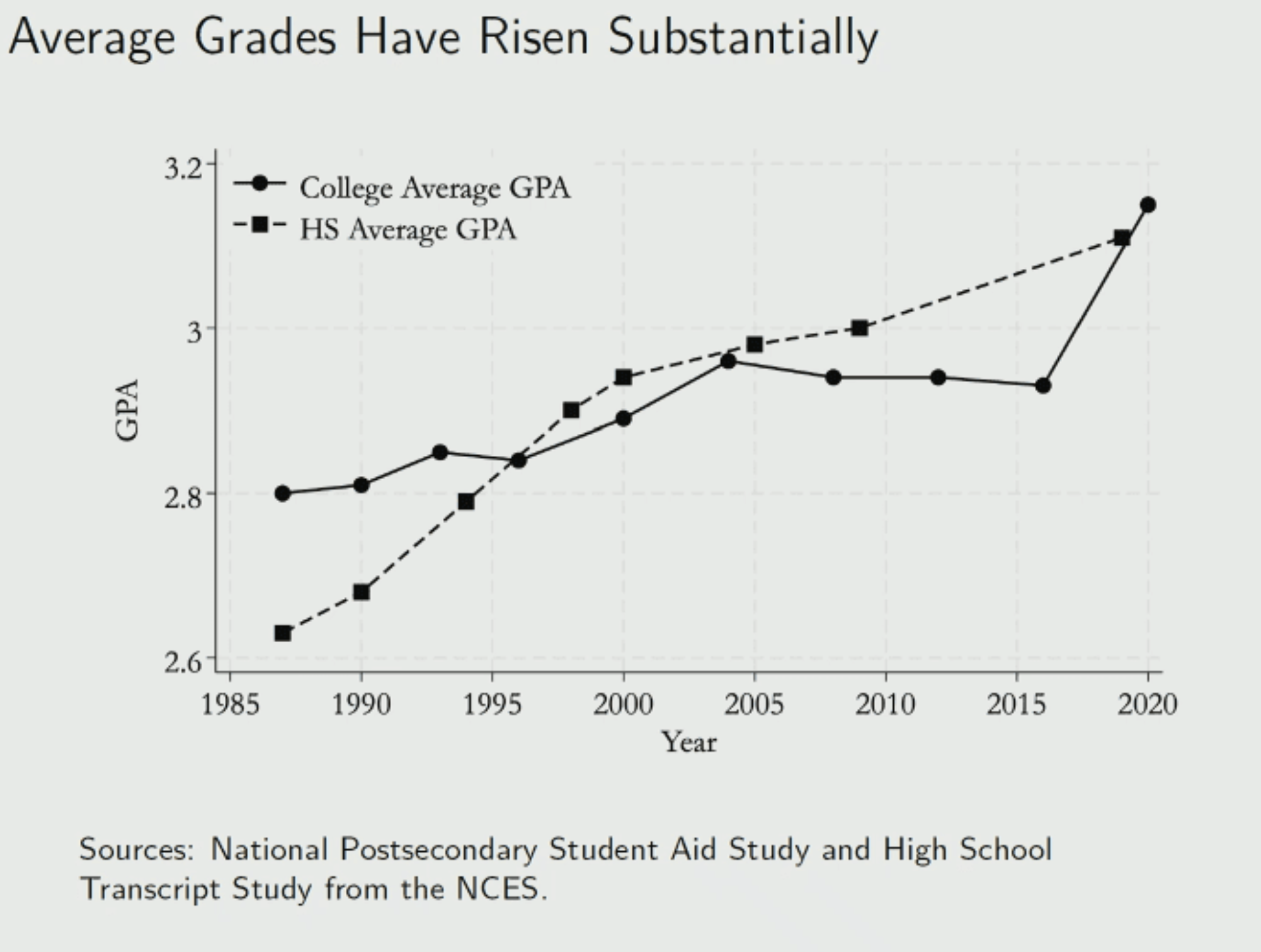

But his findings are striking and build the case against raising grades.

Students who received softer grades were less likely to pass subsequent courses, posted lower test scores afterward, were less likely to graduate from high school and enroll in college, and earned significantly less years later.

The economic cost is not small. Denning estimates that when a teacher hands out grades that are significantly higher (0.2 or more points on a 4-point scale, the difference between a B and a near-B-plus), a student in that grade loses about $160,000 in lifetime earnings measured in current dollars.

This is the effect of one teacher in one year. If a student encounters several grade-inflating teachers, the losses add up.

Evidence from two very different places

The researchers studied students in two settings: Los Angeles and Maryland.

The Los Angeles Unified School District provided data on nearly one million high school students from 2004 to 2013, a period when the graduation rate hovered just above 50 percent. The student population was more than 70 percent Hispanic, and poor grades were common.

The Maryland data tracks about 250,000 high school students from 2013 to 2023. The graduation rate exceeds 90 percent and the student population is more racially mixed. The Maryland data allows researchers to track college enrollment, employment and earnings, while the Los Angeles data ends with high school graduation.

Despite these differences, the pattern was the same.

Students taught by lenient graders — defined as teachers who gave higher-than-expected grades based on standardized test scores and students’ past performance — did worse later in high school. In Maryland, where data was available through college and the workplace, these students were also less likely to attend college or be employed and earned less.

Seeing the same pattern in two very different systems reinforces the argument that this is not a fluke of one region or one political regime.

When indulgence helps and when it doesn’t

The study makes a crucial distinction. Teachers who still kept A’s challenging but only made passing easier—turning failures into low grades—did help more students graduate from high school, especially those at risk of dropping out. This short-term benefit is real. For some students, passing Algebra I instead of failing it can keep them on track to graduate and eventually enroll in a community college.

But the benefit stops there. These students show no long-term gains in college completion or earnings. Leniency helps them get over the hurdle, but it doesn’t build the skills they need afterward.

Conversely, general grade inflation (teachers raising grades anywhere from C to B to A) shows no upside and hurts students’ chances for future success.

Why good intentions backfire

The study cannot directly explain why higher grades lead to worse outcomes. But the mechanism is not difficult to imagine. In a class with a lenient grader, a savvy student can quickly realize that he doesn’t need to study hard or do all the homework. If she earns a B in Algebra I without learning how to factor or solve quadratic equations, the knowledge gaps follow her into geometry and beyond. It can be scraped off again. Over time, the deficit increases. Trust is eroding. Learning is delayed. In college or the workplace, the consequences show up as lower skills and lower pay.

As Denning said during the presentation, there appears to be a “causal chain” of harm, even if he can’t directly measure how much less students learn or how much they fall behind.

Don’t be too quick to blame the teachers

Grading is not always an instructor’s individual decision. A 2025 Study documents the frustration of many grade-inflating teachers who say they feel pressured by administrators to follow “fair grading” policies that prohibit zeros, allow unlimited retakes and eliminate tardiness penalties.

Condescending students are not bad teachers. The study found that they were often better at improving non-cognitive skills. Their students behave better, cooperate more, and are less likely to be suspended. Yet, in this study, this does not translate into better life outcomes as one would hope.

Stricter graders tend to be better at raising students’ test scores in math, reading and other academic subjects. Despite this correlation, this does not mean that all difficult students are good teachers. Some are not.

This is early research. More research is needed to understand whether there are similar costs in the workplace than college inflation. And there are questions about whether boys respond differently than girls to inflated grades.

Teachers struggle to get students engaged in learning, which is fraught with failure, frustration, and boring repetition. Maybe low grades won’t inspire students to do that hard work. But this early evidence suggests that inflated valuations aren’t doing them any favors.

Contact the staff writer Jill Barshay at 212-678-3595, jillbarshay.35 at Signal, or barshay@hechingerreport.org.