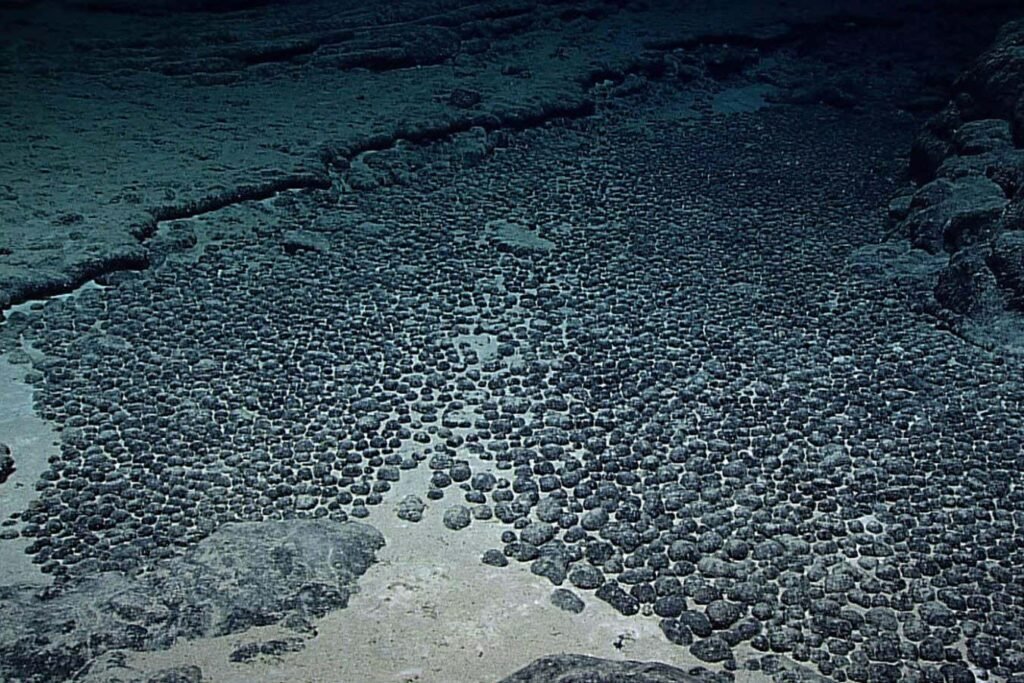

Seabed manganese nodules can be a source of oxygen

History of Science Images/Alay

This was discovered by marine scientists who made headlines last year Deep sea nodules can produce “dark oxygen”. they embark on a three-year research project to explain their findings.

Amidst the controversy surrounding their research, they head the project Andrew Sweetman The Scottish Marine Science Association says it hopes the new scheme will “show once and for all” that metallic rock pellets are a source of oxygen in the deep sea and begin to explain how the process works. “We know this is happening, and now what we need to do is show it again, and then really start to get the mechanism,” he says.

Sweetman spent more than a decade studying life on the seabed his surprise discovery made headlines in July last year, and confused the research community. Previously, it was believed that the production of oxygen was based on the presence of plants, algae or cyanobacteria for photosynthesis, driven by sunlight.

But Sweetman’s team found rising oxygen levels in nodule-rich areas of the seafloor, thousands of meters below the ocean’s surface, where light can’t get through and plants can’t grow. The researchers suggested that the nodules could act as “geobatteries”, generating an electric current that splits water molecules into “dark” hydrogen and oxygen, produced naturally without photosynthesis.

Sweetman found himself at the center of a media storm. Life changed overnight, he says, even stopping people on the street who wanted a picture with him. “It’s been very surreal,” he says.

But the discovery also brought challenges. The research has drawn criticism from some scientists and deep-sea mining companies, which plan to mine the nodules for the precious materials needed for the green energy transition.

The Metals Company (TMC), which funded some of the research that led to Sweetman’s 2024 paper, has been one of the harshest critics of his findings. Local scientists have published it a piece of paper raising concerns about the evidence and research methodology, arguing that the finding is “not fully supported”.

They say that faulty equipment or misuse of dryers can cause unusual readings, but other researchers using similar procedures have been unable to replicate the findings. They also raise questions about the data used in Sweetman’s research, saying the study is based on flawed and inadequate data.

“After decades of research using the same methods, no credible scientist has ever reported evidence of ‘dark oxygen,'” said Gerard Barron, CEO and President of The Metals Company. “Special claims require special evidence. We are still waiting.”

Concerns have also been raised with the journal that published Sweetman’s research, Nature Geoscience. “We have carefully reviewed these concerns following an established process. However, no decision has been made at this time as to what measures, if any, can be taken,” said a spokesperson for the magazine. The New Scientist.

Sweetman says his analysis is accurate and will respond to TMC’s criticisms in a formal rebuttal to their paper. But he says his experience at the center of the controversy has been “very exhausting” and upsetting. “There have been many discussions. A lot of mining companies have been saying a lot of different things, a lot of them not so nice, and that’s been a challenge to live with,” he says. “It’s definitely had a bit of an impact on me. The online harassment has not been pleasant to suffer, and it has been constant.’

Sweetman’s new research project, funded by a £2m grant from Japanese charity The Nippon Foundation, aims to put some of the controversy to rest. Sweetman’s team will use new custom-made landers capable of descending to 12,000 meters below sea level, twice the depth reached by previous research, to specifically hunt for dark oxygen production in the Pacific Ocean.

The first of three research expeditions will launch in January 2026 from San Diego, California, with the aim of confirming with fresh data the oxygen production driven by deep ocean nodules. Once again, landlubbers will seal seabed water and sediment samples to measure changes in oxygen concentrations. The researchers will also test for the presence of hydrogen, which would also be produced if the electrolysis of seawater takes place. And they will inject isotopically labeled water into the samples to trace any chemical changes in the elements.

Sweetman is very excited about the possibilities of finding dark oxygen production. “I know is happens We have found it in six places now. I know we will find it,” he says.

Another two expeditions will investigate what microbial or electrochemical mechanisms may be at play and begin to study the contribution of dark oxygen production to deep ocean ecosystems. This is the first study of its kind to directly examine these processes – Sweetman’s initial discovery was, by his own admission, “serendipity”. “I didn’t set out to show this; all we did was measure the respiration of the seabed,” he says of the initial work.

NASA is also interested in studying the nodules, Sweetman says, to investigate whether similar processes support life on other moons and planets.

Deep sea mining companies will be watching the project closely. They hope to start working at the end of the year, but they are still there Waiting for the International Seabed Authority to finalize its rules about deep sea mining. Further evidence of deep-sea oxygen production would deal a severe blow to hopes of establishing a seabed mining industry.

Sweetman says companies should hold off on leaving the seabed until scientists learn more about the role dark oxygen production may play in ocean ecosystems. “What we’re asking for is a little more time to go out and try to figure out what’s going on,” he says.

Topics: