On a brilliant mid-October morning, Harold Singletary stood in front of a teal shroud that hung from a building along one of the most famous architectural landmarks in downtown Charleston, South Carolina. A black entrepreneur, he never imagined he would be standing here, for this purpose, on a street he had walked countless times without knowing.

He prepared to address a group gathered to unveil a historic sign announcing to anyone passing by that the well-restored antebellum building behind it once housed an auction house that in 1835 “conducted the largest known sale of domestic slaves in the history of the United States. “.

A total of 600 slaves were put up for sale.

The new marker is characterized by the fact that these streetsonce bustling with businesses that were crucial to the slave trade, little of this history is told to the average passer-by. Singletary grew up in this coastal town — once the nation’s busiest slave port — where white locals until recently largely ignored racial crimes.

He held his prepared remarks in one hand. But before he spoke, he reached out to hug Lauren Davila, a stranger who found a 600-person for sale ad in 2022 when she was a graduate student at the College of Charleston. last year, a reporter for ProPublica traced the sale to a wealthy plantation operator, John Ball, Jr., which allowed Singletary to connect his family members to the sold family members and opened the door to further research into the fates of the 600 people put up for sale.

Before Dávila’s discovery, the largest known slave auction in the United States was one held over two days in 1859 near Savannah, Georgia, about 100 miles down the Atlantic coast from Charleston. 436 people were sold at that auction.

A small group then initiated the creation of the Singletary token, which was prepared for presentation.

“This is an important moment in the representation of the ancestors,” Singletary began. Among those sold by the auction firm based here were the maternal grandparents of an ancestor Singletary held in such high esteem that he named his business, BrightMa Farmsafter her. Its corporate office is a four-minute walk away.

credit:

Kathy Cleveland / College of Charleston

“America needs to face some hard facts,” Singletary said. “And those facts change the stories that change the narratives.” He thanked the people “who helped change the narrative.” Among them is the man who owns the salmon-colored building at 24 Broad Street and agreed to hang a marker on it.

Attorney Steven Schmutz purchased the two-story building in 1989 and has operated his law firm there ever since. He had no idea that the infamous slave auction was once located here.

“I just started thinking about the irony of it all,” Schmutz said. He grew up in segregated schools. Until he entered law school, all of his classmates were white. But when he was a young man during the civil rights movement, people like Martin Luther King Jr. “opened my eyes to the injustice of segregation.”

Among other things, Schmutz represented the families of those killed in the 2015 massacre at Emanuel AME Church, in which a white supremacist killed nine black worshipers. Standing in front of the marker, he applauded the work to compile a more honest account of the city’s history.

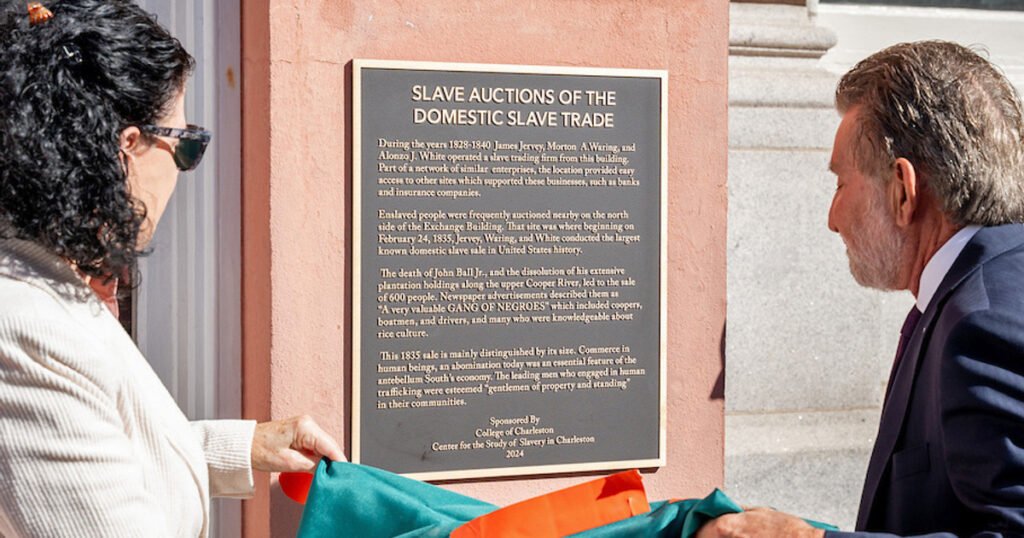

The marker, about 2 feet high, reads, “DOMESTIC SLAVE TRADE SLAVE AUCTIONS.” The auction firm Jervey, Waring & White, which operated in the building from 1828 to 1840, was “part of a network of similar businesses” around it that included banks and insurance companies, the marker explains.

The story of the marker began in March 2022, when Davila, now a doctoral student at Tulane University, was searching newspaper archives from her home in Charleston. As part of her internship, she recorded ads for slave auctions.

That day, she clicked on February 24, 1835. In a sea of classified ads, she read:

“This day, the 24th instant, and the next day, at the north side of the custom-house, at 11 o’clock, there will be sold a very valuable BAND OF NEGROES, accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED’. She was stunned.

credit:

NewsBank/Readex. Featured by ProPublica.

But the ad she found was short. It contained almost no details other than the size of the sale and the location of the sale.

A ProPublica reporter then found the original for-sale ad, which appeared more than two weeks ago. Published on February 6, 1835, it revealed that the sale of 600 was part of an auction of the estate of John Ball, Jr., a descendant slave-owning plantation regime. Ball died last year and five of his plantations were put up for sale – along with the people who were enslaved on them.

A descendant of Ball named Edward Ball wrote a best-selling book in 1998:Slaves in the family,” which details the skeletons of his family and the horrors that are at length minimized by a lost cause narrative about benevolent slave owners. Ball discovered the descendants of the people his ancestors had enslaved, including Harold Singletary.

Dávila’s research was supported by the College of Charleston’s Center for the Study of Slavery and a white Charleston resident named Margaret Seidler. At 65, Seidler discovered the infamous slave traders in her family tree and then she began to identify others – including Jervey, Waring & White.

Seidler wrote a book about his findings and appeals to other white Charlestonians to help tell an honest story about the city’s slave history. She and historian Bernard Powers, founding director of the Center for the Study of Slavery, clicked on the marker.

“The truth can be a tonic,” she said.