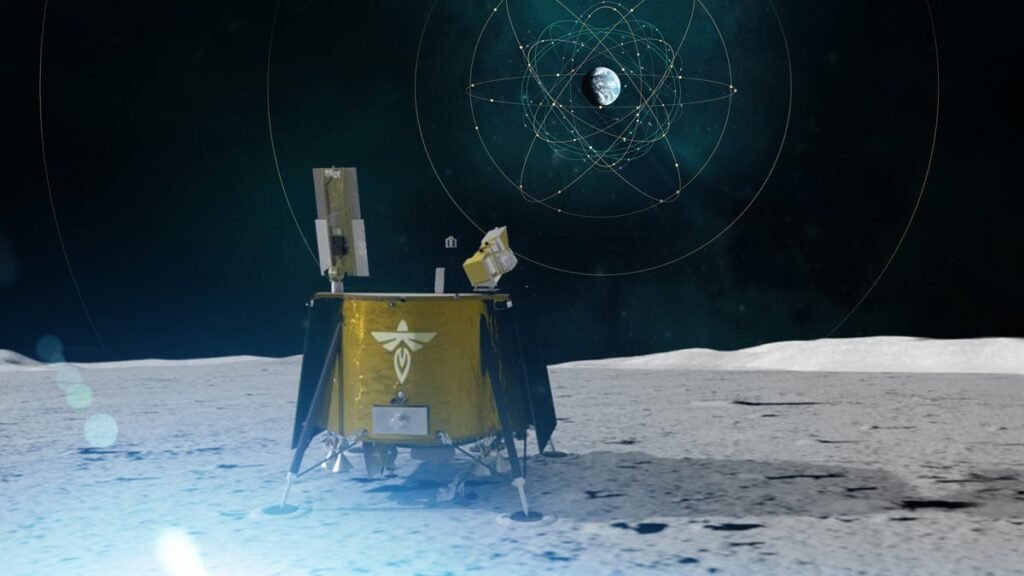

In the country classic “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” a cowboy receives a terrifying vision: the devil’s herd of cattle thundering through the clouds, “on that ridge up in the sky forever / Chasing the souls of the cowpokes that must ride forever.” horses snorting.” At 1:11 a.m. EST on January 15, Blue Ghost, a lunar rover built by Texas-based Firefly Aerospace, rode its fiery horse across the sky, blasting off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in what would become the second U.S. mission. The moon landing since the end of the Apollo program.

Over the next four weeks, that mission — called Ghost Riders in the Sky, or Blue Ghost Mission 1 — will see his spacecraft orbit Earth at ever-increasing distances. Carrying a suite of scientific instruments created by NASA, Blue Ghost will race to the moon. The mission is flying under the US Space Agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, which promotes private companies to take delivery of these lunar instruments and supplies as part of the nation’s ambitious Artemis lunar program.

“(The Moon) is like a gateway to our solar system; it’s an ‘easy’ place to go and learn to be productive,” says Ray Allensworth, spacecraft program director at Firefly Aerospace. “The basic science we’re gathering on these CLPS missions has applications not just for Artemis, but for interplanetary conversion as well.” .

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

Blue Ghost Mission 1 marks a new chapter for Firefly, which has been developed and launched his rocket but nothing has ever flown to the moon. It’s also another major test of the CLPS, which will pay $2.6 billion to private companies for lunar missions. NASA hopes to save a lot of money through the program. In February 2021, Firefly received NASA’s contract for Blue Ghost Mission 1, now worth $101 million, less than the agency would spend to build its own lunar lander.

“A lunar surface landing, done the traditional way, is north of half a billion (dollars). … I’ve never seen a quote that’s lower,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s Science Mission Director. Management was its associate administrator from 2016 to 2022 and championed the development of CLPS. “Every one of those shots on goal is being done without a top and with their own systems.”

NASA also hopes CLPS will increase the frequency of robotic lunar missions. Blue Ghost is the third spacecraft launched under the CLPS banner since January 2024, and at least one more launch is on the books for this year. Before CLPS, the last US soft landings on the moon occurred during the Apollo program, which ended in 1972.

“There’s a significant portion of NASA and the scientific community that didn’t live, or at least was on staff, to see the moon landing,” says lunar scientist Ryan Watkins, program scientist for NASA’s Exploration Science Strategy and Integration. the office “To finally be able to get to the surface and get some of these questions in situ is really exciting.”

But in exchange for lower costs and faster response times, NASA allows private companies to design and operate their own lunar fields, generally increasing the chances of any CLPS mission failing. Since the program’s inception, NASA leaders, including Zurbuchen, have insisted that each initial CLPS mission has a roughly 50-50 chance of success.

As expected, the results of the program so far they got mixed up. Last January, the Pittsburgh company Astrobotic launched a lunar lander with loads of NASA and non-NASA payloads just to make the spacecraft suffer. critical anomaly shortly after launch. Then, the following month, a robotic lander built by Houston-based Intuitive Machines flew a CLPS mission to the moon’s south pole. Although the spacecraft survived the descent…a first for any commercial lunar mission—One of the legs was broken during the touchdown, partially overturning the landing.

“I want (CLPS) to work, but this is an experiment, and we don’t know if it’s going to work,” says Casey Dreier, head of space policy at the nonprofit Planetary Society.

About two meters tall and 3.5 meters wide—roughly the size of two Volkswagen Beetles parked side by side—Firefly’s Blue Ghost lander is designed to carry a 150-kilogram (330-pound) payload to the lunar surface. On Blue Ghost Mission 1, the lander is flying 10 NASA instruments, the agency’s largest number of payloads yet launched on a single CLPS mission.

For Firefly’s engineering corps, many of them still in their 20s, building the Blue Ghost has been a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and challenge. “It’s awesome,” says Allensworth. “It’s really special, but it can also be scary at times because none of us have built a moonship before.”

Perhaps no system on Blue Ghost exemplifies this challenge more than the rocket engines responsible for setting the lander on the lunar surface. Shortly after completing a major design review of Blue Ghost in October 2021, Firefly engineers realized they needed to build their own reaction control system (RCS) thrusters, which control a spacecraft’s orientation and stabilize its position. In August 2024—less than three years after the start of its work—a team led by engineer Ryan Cole finished sorting out engines for flight.

“Conventional wisdom would have said, ‘Well, you’re never going to make an RCS engine in less than three years,'” says Cole. “But none of us had it in our heads that this was impossible.”

The Blue Ghost now faces approximately six weeks of travel before putting those engines to the final test. After 25 days around the Earth, the lander will spend four days flying towards the moon. It will then spend another 16 days in lunar orbit before making a landing attempt in early March. As it turns out, Blue Ghost isn’t the only spacecraft traveling to the moon. The lander shared its launch with Hakuto-R Mission 2, a lunar lander and rover developed by Japanese company ispace. whose first landing attempt in April 2023 it crashed just a few miles from the moon’s surface.

At NASA’s request, Blue Ghost Mission 1 is targeting a landing site on Mare Crisium, a dark-colored basin about 560 kilometers (350 miles) long that was formed when lunar lava filled a then-new impact crater. The field is believed to better represent the average composition of the moon than the Apollo landing sites. Blue Ghost’s goal is to operate there for 14 days, including five hours of the long and bitterly cold moonlit night.

Some of Blue Ghost’s payloads will showcase new technologies. For one thing, Blue Ghost is flying an instrument that will test whether the lunar landers can detect and use the signals. From the GPS satellites orbiting the earth. Another payload will try to combat lunar dust—tiny, strange particles that are terrible for astronauts and hardware. to throw electric fields off a surface.

Other instruments will study the lunar interior. One, called THE LIST (Lunar Instrumentation for Subsurface Thermal Exploration with Rapidity), is designed to measure how heat flows from the moon, which should help shed light on the deep structure of our natural satellite and its evolution over eons. The device consists of a thermometer on the tip of a probe, which will drill up to three meters into the lunar soil, throwing bursts of compressed gas. If successful, LISTER will set the record for the deepest mission ever to drill into the lunar surface.

“Gas, in a vacuum, is like a grenade … So we thought, ‘Why not dig deep holes with it?'” says Kris Zacny, vice president of exploration systems at Honeybee Robotics, a Blue Origin-owned company that developed it. THE LIST “It’s like pointing a garden hose at the soil and creating a trench.”

Regardless of what happens with Blue Ghost Mission 1 — whether it lands on the moon’s surface in one piece or several — the experts interviewed. American scientific say, for now, the CLPS initiative will likely last into the second term of US President Donald Trump, who takes office on January 20. Along with Artemis as a whole, CLPS was created during the first Trump administration and continued into the Biden administration. . This was the first time since Apollo that an ambitious US lunar program had survived a presidential transition.

“I think this particular launch, in and of itself, doesn’t need to change the program, regardless of (the outcome),” Zurbuchen says. “We’d all be more excited (if) everything went as we hoped it would. . . . If it didn’t succeed, I’d basically say, ‘Hey, we never said we needed any of these things to be successful.’

“(CLPS) is not a national standards program,” Dreier added. “In a sense, if it works, it creates a fundamentally new capability.”

That said, the structure of Artemis may have more changes this time. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, who passionately supports the strategy of the first human space exploration of Mars, was a major backer of Trump’s 2024 campaign and is a major influence on the incoming administration’s policy agenda. A report from Ars Technica last December suggested Trump’s transition team he was looking at the changes Big credit to Artemis and NASA, including the cancellation of the space agency’s expensive Space Launch System rocket, the centerpiece of the current Artemis plan.

Any such proposal will have to be made through Congress, however, he has repeatedly stated he wants the moon as soon as possible strategy in line with Artemis’s status quo. Major changes could also risk disrupting existing agreements with commercial companies and other countries’ space agencies. “There is frustration, you see, that (Artemis) is not optimized for results; is optimized for politics. But you have to work with politics in the end,” says Dreier. “We shouldn’t throw away such a hard-won coalition.”