Instead, the institutions moved on.

“We’ve basically aged out of it,” Levine said, speaking to the American Enterprise Institute in January about the challenges of higher education. “Pretty soon the people who were at home were no longer in college. That’s a relatively short number of years.”

There were innovations. In what we would now call distance learning, colleges expanded correspondence courses. In 1922, Penn State became the first institution to use radio for instruction. Enrollment of women is increasing, especially in nursing.

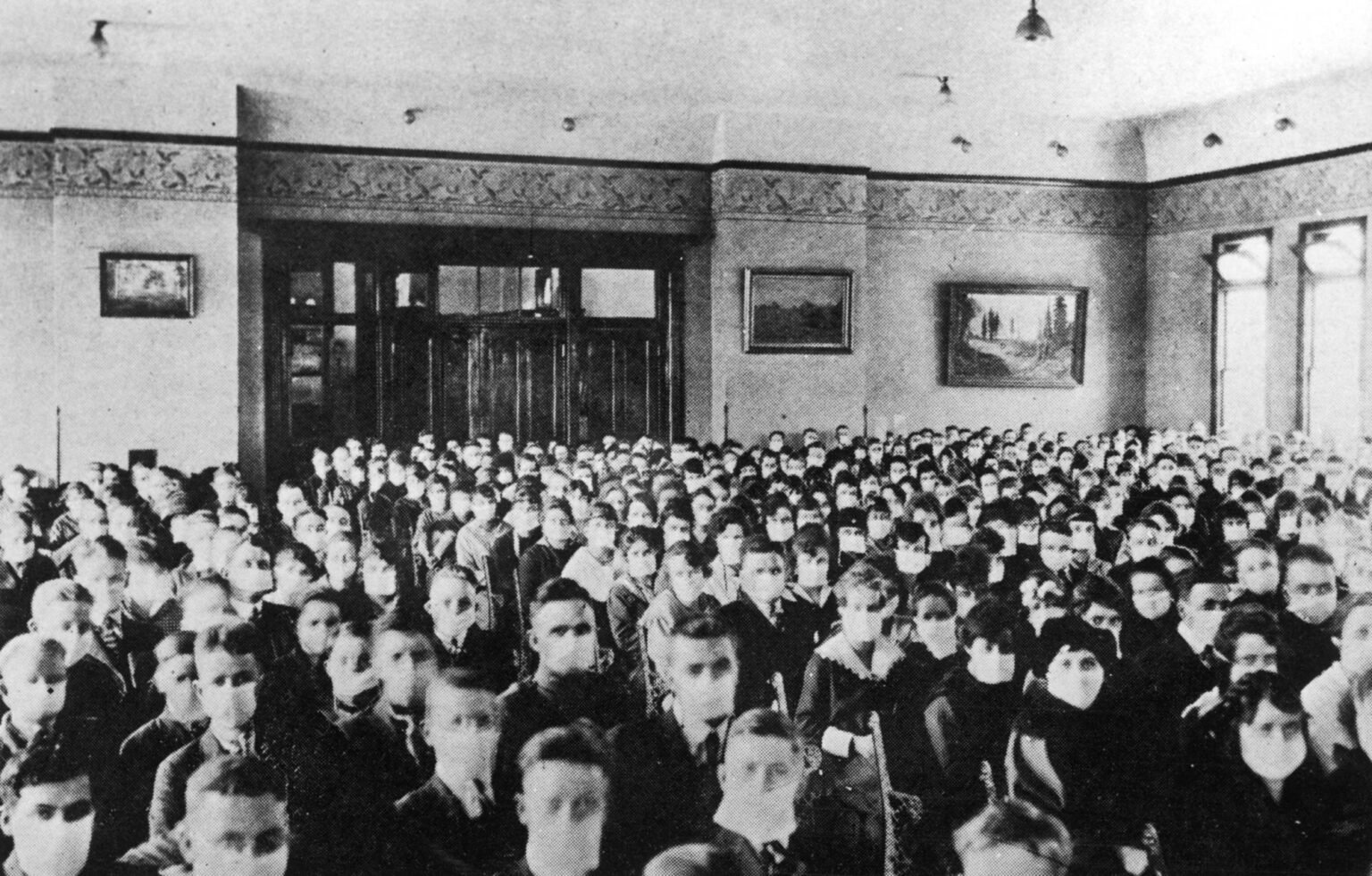

But there was little evidence of repair or restoration. Students, whose education had been interrupted by both World War I and the pandemic, were outnumbered and with a changed perspective. They will become known as the lost generation: disillusioned, cynical, psychologically scarred and searching for meaning in a world that has failed to make sense.

What kept this loss from registering as a lasting crisis was the scale. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, only about 5 percent of young Americans attended college. There were far fewer colleges and universities. And higher education was not yet central to economic and social life in the way it is today. When one cohort wavered, institutions simply admitted the next. Replacement took the place of restoration.

Still, the cultural effects were visible. Writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and F. Scott Fitzgerald chronicled the long disillusionment of a generation shaped by war and disease. The Roaring Twenties, Levine argues, were less a sign of healing than a backlash, followed a decade later by the Great Depression.

Levine does not romanticize the past. “Everything I’ve read makes it sound like the Spanish flu combined with World War I might have been a more difficult problem,” he said in an interview. “So many lives were lost — not just students, but faculty and staff. Mental health resources were primitive.”

The parallels with the present are disturbing, but the differences may matter even more. Today, more than 60 percent of young adults attend college immediately or shortly after high school. Higher education has become a mass institution deeply intertwined with economic mobility and social identity. And Covid didn’t just get in the way of learning; this necessitated prolonged social isolation in the formative stage of teenagers and young adults. Levine notes that it is impossible to separate the effects of the pandemic from the rise of smartphones and social media, which are already changing the way young people relate to each other.

Enrollment drops after Covid repeats those of the Spanish flu era. But replacement may no longer be a viable strategy. When higher education serves a small elite, institutions can quietly absorb the losses. When it serves a majority, the consequences of disruption are wider, more visible and harder to prevent.

The lesson of the Spanish flu is not that young people inevitably come back. It is that the institutions endured, waiting. A century ago, this carried limited costs. Today, with a much larger and psychologically more vulnerable young adult population, the cost may be much higher.

This story of how spanish flu concerned universities is produced by The Hechinger Reportan independent, nonprofit news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Evidence points and others Hechinger Bulletins.