The question was simple: had Nike, a brand of sportswear, which was charged with plumes more than two decades ago, really becoming a beacon of environmental supervision and just work practice, as claimed?

As the editor of the Northwestern PROPBLICA team and the long-standing Areganon, I wanted to know the answer as a reporter based in Portland, who raised the question, Rob Davis.

Nike is woven into the oregon fabric. It is one of the largest Portland employers and one of the few companies in Fortune 500. Nike headquarters in the suburb of Portland is a 400-hectare complex of buildings, launched trails and sports fields where fashion and athletics design are found. At Oregon University, the Nike Co-founder Alma Mater, buildings all over the campus are his name or their relatives.

The trouble was that the answer to Davis’s question was primarily over the Pacific. Although PROPBLICA does not experience stories that require time and yes, money – see Last reporting For example, journalists Josh Kaplan and Bret Merphy from Gambia – Davis first needed to prove to the editors that a foreign trip would bring us a story that broke the new soil.

One of our most important solutions was to cooperate with the reporter Matthew Kish and his editors at Oregonian/Oregonlive, where Davis and I worked before. Kish covered Nike for more than ten years and has known the company, as well as any reporter in the country.

Kish and Davis began to consider public messages that Nike has posted over the past two decades, and every news article they could find about the company’s efforts. Davis talked on the phone with supporters of work around the world. He even found several factory workers in Asia, ready to talk in late night (for them) videos about his working conditions.

The Hreum, which Davis and Kish could not crack, was Nike himself. Reporters told the Nike public relations team about their interest. Can Nike staff share what they found at the plant or how they provide Nike’s maintenance rules? PR-people presented some reference information at different points, including excerpts of past corporate reports, but the company decided not to make anyone accessible to the interview record at this stage.

(I also asked Nike last week to weigh the company’s interaction with Kis and Davis, or about the stories they wrote for this series; Nike’s press -secretary refused to comment on me.)

Last year, the dismissal that got into Nike, Kish and Davis had an opening to talk to insiders about one specific aspect of the social responsibility company. Continuing the hint, they worked with the reporter of Alex Mireski’s research to make a list of staff who worked as sustainable development. Reporters started knocking on a virtual door: about 100 of them. They found that the reorganization of the Nike took a great deal of work on the workforce, the efforts of which included a decrease in carbon emissions.

This time, Nike answered by interviewing its Chief Sustainability Director, the only interview that the company has given this project for more than a year of reporting. It lasted 17 minutes. She said the company remains committed to resistance and described its strategy as “built” work throughout the company.

We have published stories that are outlined departure And another development that seemed to go against the proclaimed Nike intention to help the planet: Increased emissions in private planes.

But something was missing in our reporting. Former sustainable development workers spoke in English. Many were in Oregon. They had internet presentations. Understanding the working conditions at Nike factories called for a higher point of view in the distant foreign supply chain of the company.

Davis abandoned one specific Nike claim. The company stated that the factories for which they have data is paid by their employees, an average of 1.9 times more than local wages. This did not involve the proceedings of the factories that are included, and it was not clear how widely it could be compared to the average. So Davis started asking Paystubs for workers around the world. We hoped that even scattered data would help us check the Nike Mathematics.

Paystubs sounded. Several workers from the factory in Central America. More from Indonesia. Parcel from Cambodia.

Then, the breakthrough.

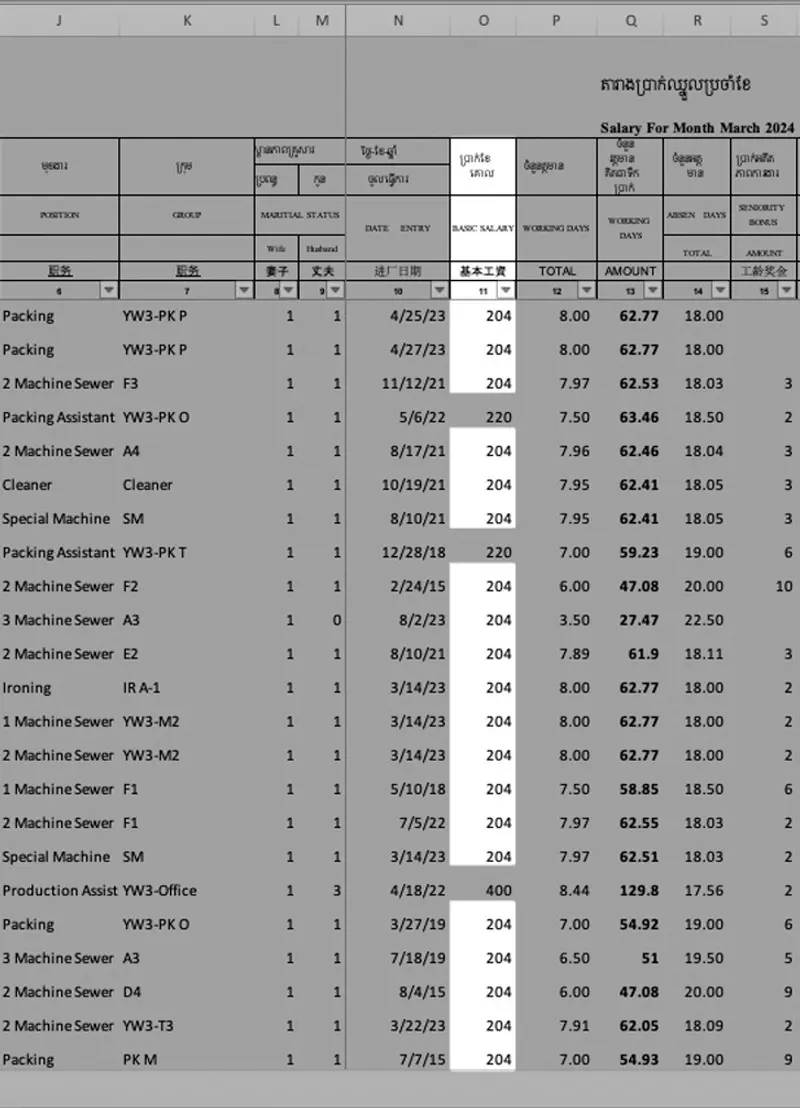

Davis received an Excel spreadsheet in English and Khmer, the language that spoke most widely in Cambodia. It was a salary for clothing Y & W, which made baby clothes for Nike from 2022 to 2023. Davis could see the title of work of each employee, age, hiring date, gender and payment amount.

It was one factory in the supply chain consisting of hundreds, 3 720 workers with more than 1.1 million that Nike suppliers are working worldwide. But it was clearly a comprehensive window. Fast calculations showed that only a A tiny share of the workforce y & w .

Credit:

Received propublica. Highlights and Editorial Board Propublica.

Davis contacted a bilingual journalist -Freelancer in Pnopen, Keith Sorittev, who found some workers mentioned in the Book of Wages. Now we had factory sources on the ground. We had anyone helped Davis translate what they should say. And we had an electronic table. I told Davis to book a ticket for January.

On Sunday morning, less than a day after his plane landed in Cambodia’s capital, Davis met a group of workers on his only day off. After getting acquainted through our mercenary translator Davis pulled the iPad out of the road bag and handed it over whether the digital book was accurate.

One by one, each worker studied the record by his own name. “Correct?” Davis asked. Pause for translation.

“Yes.”

At the table they went: right. Yes. Correctly.

Credit:

Rob Davis / PROPUBLICA

Davis spent the rest of his 12-day visit, traveling by the tuk-tuk-tricycle, called his engine to meet the workers in the small villages around Pnopen. Cambodian workers tend to be at least six days a week, leaving limited leisure to spend with your family or journalist. However, with the help of a whale, Davis managed to talk with just 14, some want to identify by name. They told him that the money they earned at the 48-hour working week was not enough to live, and that they needed overtime to bring the ends.

Credit:

FIRST PM: Keith Sorittevi. Second image: Rob Davis/PROPUBLICA

When the workers began to say Davis that people lost consciousness at the hot factory and they needed to be treated at his clinic, he told me to determine my reaction. I asked: could he find a doctor who handed them? Very soon Davis got a phone number for a clinic ready to talk. A medical worker helped us quantify the scale of the problem by saying Davis as A lot of 15 people per month became too weak to work in the hot months of May and June. (As used in Cambodia, this term “consciousness” can describe too weak to work.)

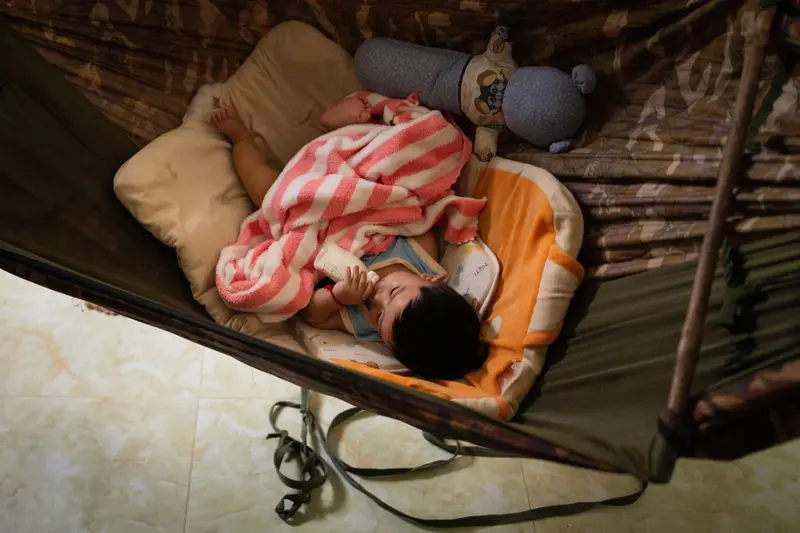

PROPUBLICA Photojournalist Sarabet Mani moved to Davis’s trail in a month. With an intimate portrait, she recorded the home life of people from the factory, where the basic payment began about $ 1 per hour.

Credit:

Sorobit Mani/rivers

Nike did not answer the detailed questions of Davis about wages or troubles, instead issued a written statement. The company said it “strives for ethical and responsible production” and that it expects the suppliers “continuing to succeed in fair compensation for the usual working week.”

Representatives of the Y & W Araarment and his parents Hong Kong, Wing Luen Kniting Factory Ltd., did not respond to Davis’s emails, text messages or phone calls. Brands Haddad, which Y & W workers reported to Davis, served as a Nike at the Phnom Pench facility, did not respond to the e -mails that asked about the conditions.

As Davis was engaged in his history, President Donald Trump’s plan to raise tariffs for goods manufactured abroad has directed a drop in Nike shares. One of the stated goals was to change the economic forces that forced Nike and others to make their products in places such as Cambodia, and not in the US, this, frankly, as, for example, Nike results in the region may lose relevance.

But the experts said Davis and Kisha, our partner in Orange, quite the opposite. Instead of bringing jobs home, brands can simply squeeze their foreign vendors for greater performance.

This created the problems that caused Davis from the beginning, as and when -the. If Nick fulfilled his promises in Southeast Asia?

At one of the Cambodian factory, Davis stubbornly brought us a simple answer: no.

Credit:

Sorobit Mani/rivers