January 8, 2025

5 read me

NASA’s Mars Sample Return Program Faces Stark Choices

NASA sees two paths to save its mixed plan for retrieving materials from the Red Planet, but won’t choose between them until 2026.

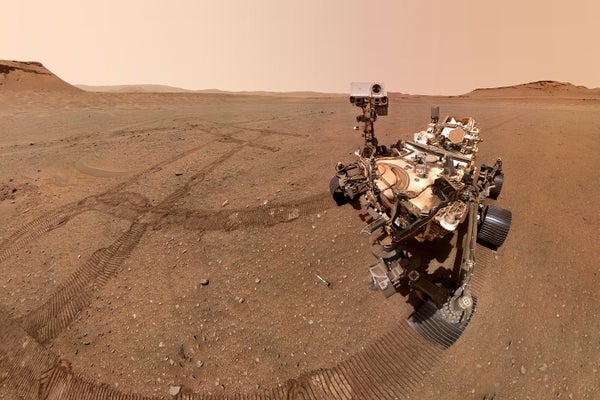

NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover appears in this January 2023 selfie next to several sample tubes scattered across the Jezero Crater landscape. The space agency is developing a new plan to analyze most of Perseverance’s samples on Earth in the 2030s.

of NASA Mars Sample Return program problems it’s stuck at a crossroads—and it’s likely to be in limbo until at least 2026—said agency officials at a press conference on Tuesday.

Called MSR, it was a joint effort between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). decades in the making. It is widely seen as a hub for US and European interplanetary science and exploration in the near future, and as a first step towards more ambitious human missions to Mars. Its initial phase is already underway: NASA’s Mars rover Perseverance has spent much of the past four years orbiting a vast lake bed and river delta deep within the Red Planet’s Jezero crater, where it resides. full samples into some of the 43 cigarette-sized titanium tubes on board. Studying these materials, scientists say, would at least transform our understanding of the solar system’s early history, when Mars was warmer, wetter and presumably more habitable. And in principle, samples could also be delivered the first discovery of extraterrestrial life.

NASA’s original MSR plan to bring this precious cargo to Earth in the early 2030s, as intended, called for a landing around 2027–2028; It would encounter Perseverance on the Red Planet and transfer the samples to a vessel inside the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV). MAV would do it blast off mars To rendezvous in space with an ESA-provided Earth Return Orbiter, to return the sample vessel for a final parachute-decelerated dive to the surface of our planet.

About supporting science journalism

If you like this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you’re helping to ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

But this complex choreography faced strong political and fiscal headwinds in September 2023, when a formal review revealed that the MSR’s estimated cost had risen from about $4 billion to about $4 billion. 11 billion dollar budget—all to return precious samples to Earth before 2040. US lawmakers threatened. total cancellationand NASA Administrator Bill Nelson stopped the MSR, causing layoffs and increasing anxiety At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, or JPL, the space agency that runs the MSR program. Meanwhile, NASA began to solicit proposals for new plans internally, as well as from outside commercial companies. Last October the space agency created one independent strategic review team evaluate the 11 accepted proposals and draw a path forward.

Tuesday’s speech revealed the results according to that independent evaluation, giving two potential options for a faster and cheaper MSR. Both seek to save costs by giving Mars less mass. They also share some related features, such as equipping the sample recovery lander with a simpler replacement robotic arm left over from Perseverance’s development and redesigning the MAV to use a dense radioisotope electricity source rather than more sophisticated solar panels. The first option for a sample recovery lander on Mars would use an improved version of a proven technology: a “sky crane” platform developed by JPL. It landed the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers. The second would instead carry the sample retriever lander to the surface of Mars in an as-yet-unspecified heavy commercial vehicle, possibly some variant of the massive rockets being developed by companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin.

“Either of these two options is creating a much more simplified, faster and cheaper version than the original plan,” Nelson said at the conference. The overhead crane approach, he said, would cost between $6.6 billion and $7.7 billion, while the commercial heavy-lift option would cost between $5.8 billion and $7.1 billion. ESA’s cargo-ferrying orbiter could lift off from Earth in 2030, and land to grab NASA’s samples in 2031. And the return to Earth could happen in 2035 or even 2039.

But, citing the need for more detailed engineering studies, budgetary uncertainties and deference The incoming administration of US President-elect Donald Trump—Nelson said that NASA will not choose between the two options until mid-2026. And to sustain the program, he added, congressional appropriators would have to allocate at least $300 million to MSR in the current fiscal year — an amount that would be maintained every year going forward. “

“I think it was a responsible thing to do, not to give the new administration the only alternative,” Nelson said, “Even if they want a sample from Mars back, I can’t imagine they won’t.”

Nicola Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, was optimistic about the new plan. “I’m excited about both ways,” he said. “I think we can really do it if we work together with our partners, our international partners, our commercial partners, our amazing expertise at NASA.” The Perseverance rover, he noted, is “very healthy and stable” on Mars and has already filled its 28 titanium tubes. carefully curated samples Martian rock, sediment and air. Ten of these tubes have been stored on the planet’s surface as a backup in case the Perseverance breaks down and cannot travel to a recovery ground. The new plan calls for it to be abandoned in favor of bringing back a more prominent haul: 30 tubes to be stored inside Perseverance, which will hopefully be fully operational by the 2030s. Meanwhile, Fox said, “there are still 13 attractive pipelines left to fill … We are very confident that we can return 30 samples before 2040, and … for less than $11 billion.”

That push for larger sample numbers sounds exciting to MSR’s chief scientist, Mars expert Meenakshi Wadhwa of the University of Arizona. “I’m particularly pleased that the goal is to return 30 sample tubes by 2035,” he says. These samples “will answer fundamental questions for us as humans and revolutionize our understanding of the processes of planet building in our and other solar systems.”

Harry McSween, of old Mars sample return supporter and a professor emeritus at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville also emphasize the importance of recovering as much material as possible. “The scientific yield of MSR requires samples collected from a carefully selected site to answer critical questions, not just sampling anywhere on Mars,” he says. This stands in stark contrast to what may be the strongest motivator for MSR’s continued political support: a competitive effort to return China’s samples, it seems to assume. A much easier “grab and go” mission to retrieve a number of samples from a single easily accessible location on Mars. This could push China to the finish line in an imaginary race to return Martian materials to Earth, but at a high scientific cost.

Others aren’t so sure Tuesday’s announcement is something to celebrate. “I’m glad the MSR wasn’t canceled, but we need to make a decision and move forward sooner rather than later,” says Casey Dreier, head of space policy at the Planetary Society. “I’m concerned that the MSR has been in limbo for so long… The only way forward we were promised is more examinations. NASA has to commit to a mission or not and decide where to go from there.”

For Dreier and others, the choice is between a presumably JPL-driven sky crane — a “go with what you know” approach — and a greater and more rigorous reliance on commercial enterprise innovations. For the latter, “obviously (NASA) is talking about SpaceX, which is the only viable company that would take that capability through Starship,” the heavy-duty, fully reusable vehicle SpaceX is developing, Dreier says. “That requires the Starship to be working, though, and (to get) to Mars.” Using the Starship Dreier adds that “MSR could make a stronger case for serving as an unmanned demonstration mission for a future Mars campaign.” This could align this high-priority NASA science mission with the space agency’s broader goals in human spaceflight.

“I think there’s a way there,” Dreier concluded. “But that still involves a lot of unknowns.”