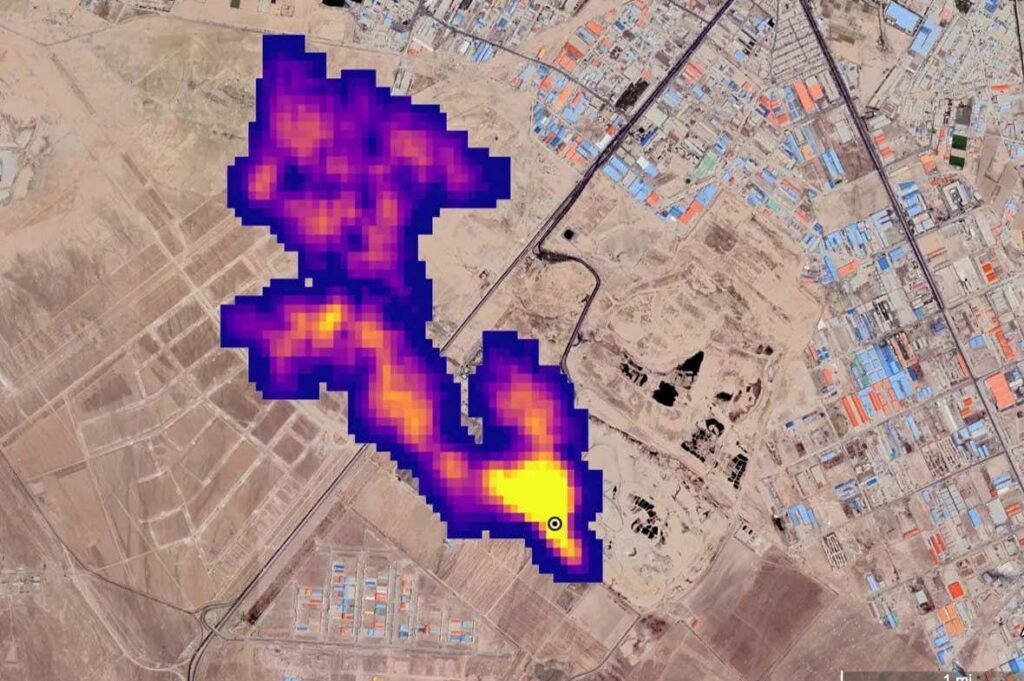

A plume of methane at least 4.8 kilometers long enters the atmosphere south of Tehran, Iran.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

The world has more ways than ever to detect the invisible methane emissions that are responsible for a third of global warming until now. But according to a report released at the COP29 climate summit, methane “super-emitters” are rarely taking action to warn that they are leaking large quantities of the powerful greenhouse gas.

“We don’t see the transparency and sense of urgency that we need,” he says Manfredi CaltagironeDirector of the United Nations Environment Program’s International Observatory on Methane Emissions, which recently launched a system that uses satellite data to alert methane emitters of leaks.

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas, after carbon dioxide, and an increase number of countries They have promised to reduce methane emissions to avoid near-term warming. last year COP28 climate summitmany of the world’s largest oil and gas companies also pledged to “eliminate” methane emissions from their operations.

Today, a growing number of satellites are beginning to detect methane leaks the biggest sources of these emissions: oil and gas infrastructure, coal mines, landfills and agriculture. This data is essential to hold the senders accountable, he says Mark Brownstein In the Environmental Defense Fund, an environmental group that has recently launched its own methane detection satellite. “But data alone doesn’t solve the problem,” he says.

The first year of the United Nations methane warning system shows a wide gap between data and action. Last year, the program It has issued 1225 alerts to governments and companies when he identified methane plumes from oil and gas infrastructure large enough to be detected from space. It now reports that broadcasters have taken steps to monitor these leaks only 15 times, a response rate of about 1 percent.

There could be several reasons for this, says Caltagiron. Emitters may not have the technical or financial resources and cutting off some sources of methane may be difficult, even if emissions from oil and gas infrastructure are seen as the easiest to deal with. “It’s plumbing. It’s not rocket science,” he says.

Another explanation could be that broadcasters are still getting used to the new alert system. However, other methane monitors have reported a similar lack of response. “Our success rate isn’t much better,” he says Jean-Francois Gauthier At GHGSat, a Canadian company that has been providing satellite alerts for years. “It’s about 2 or 3 percent.”

Super-emitting methane plumes were detected in 2021

ESA/SRON

There have been some successes. For example, the UN this year issued multiple alerts to the Algerian government about a source of methane that has been leaking continuously since at least 1999, a global warming effect equivalent to half a million cars driven in a year. By October, satellite data showed it had disappeared.

But the overall picture suggests that monitoring is not yet translating into emission reductions. “Showing methane plumes is not enough to generate action,” he says Rob Jackson at Stanford University in California. A major problem he sees is that satellites rarely reveal the owner of the spillway or the well that’s leaking the methane, making accounting difficult.

Methane is one of the main topics of discussion at the COP29 meeting, now in Baku, Azerbaijan. A the peak this week”Greenhouse gases other than CO2”, called by the US and China, the countries announced various actions on methane emissions. The US is introducing a methane tax, which targets oil and gas emitters, although many expect the incoming Trump administration to scrap the rule.

Topics: