November 15, 2024

4 read me

Completing NASA’s Chandra will take us out of the high-resolution X-ray universe

The Chandra X-ray Observatory is closed. Closing it would be a loss for science as a whole

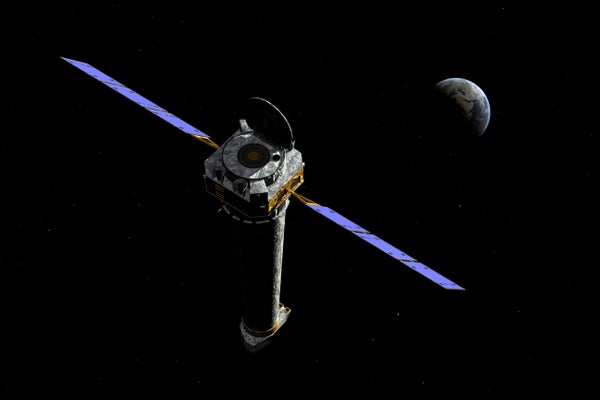

As NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory can appear about 50,000 miles from Earth, nearly twice as far as Earth-orbiting geosynchronous satellites.

Walter Myers/Stocktrek Images Inc. Alamy Stock Photo

The Chandra X-ray Observatory is the darling of high-energy astrophysics. Famous for providing unique X-ray images of supermassive black holes, exploding massive stars, and even dark matter infusions. collisions between galaxy clustersthe spacecraft probes the greatest mysteries in astrophysics

But 25 years after seeing his first lightIt is Chandra’s future up in the air.

In March, NASA made the cut Chandra’s budget From $68 million in 2024 to $41 million in 2025 and $26 million a year later. According to the Chandra X-ray Center, which operates the telescope, this only allows the mission to be shut down. In the months since then, several events—including life— advertising campaign and the show conference support– has He kept Chandra funded Until September 2025. But for this year’s Senior Review, which evaluates NASA’s missions, the Chandra X-ray Center has been told to stay within proposed budget numbers, which means planning how the spacecraft will be powered down.

This is a mistake. Chandra should continue to operate until it encounters a critical failure or is replaced by a comparable mission. It’s Chandra alone high-angle-resolution x-ray telescope in space, and there is no mission with a similar capability to replace it Until 2032 at the earliest.

One might ask: What new discoveries can Chandra make that haven’t been made in the last 25 years? And that’s a good question. But our observing capabilities have changed a lot since Chandra was launched, so it has the potential to make discoveries that require multiple telescopes. we have recently reached the multi-wave age, multi-message astrophysicsenabling simultaneous views of stars and galaxies from the radio spectrum to gamma rays, neutrinos and gravitational waves. Much of this critical synergy will be lost and wasted if we abandon high-resolution x-ray coverage.

In a sense, he was Chandra before his time. Some discoveries he will remember, for example Detecting sound waves from supermassive black holesThey are Chandra’s only science. But his most significant recent results come from the combination of sharp X-ray vision, for example, with new instruments The James Webb Space Telescope or Event Horizon Telescope.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory was the heaviest payload carried into space by a shuttle. He has been studying supernovae, black holes and spiral galaxies for two decades.

In 2017, when gravitational waves emitted by two merging neutron stars reached Earth, every major observatory in the world made follow-up observations in this unprecedented celestial event. As a result of the merger of binary neutron stars a kilonova explosionwhich shone across the electromagnetic spectrum. Its X-ray emission was due to the acceleration of particles in the explosion’s blast wave and gave us information about the material surrounding the binary. No other facility could have localized the merger as precisely as Chandra: our understanding of one of the most important astrophysical events of modern times would be incomplete without it.

After a quarter of a century, Chandra is a well-oiled machine with an experienced team that has adapted to older telescopes. Keeping Chandra running at the forefront of astronomy is “increasingly complex, but not expensive. We’re getting better every day,” says Daniel Castro, an astrophysicist at Chandra Science Operations.

The crux of the matter is in the presidential budget request of last March, which communal surprise He said that chandra is rapidly degrading and becoming more and more expensive. Another source of community frustration is that NASA sidestepped its peer review process to assess the timeliness of the mission’s end, the Senior Review (which gave Chandra its highest marks in 2022), unexpectedly cutting off Chandra’s funding. Budget cuts end the Chandra mission without any discussion or input from the astrophysics community.

An interesting option from NASA was to provide 50 million dollars for development Living World Observatoryor HWO, where the funding itself would make Chandra fully operational. HWO is NASA infrared, optical and ultraviolet the most emblematic telescope that’s 20 to 30 years from launch, and will likely cost upwards of $6 billion to $10 billion.

Webb, whose costs skyrocketed from the start 2 billion to 8 billion dollarsis large in the decision to prioritize HWO funding. It is commendable that NASA is looking ahead to future challenges, but much of this first funding allocation for HWO will go into upfront costs, such as building a project office and establishing industry partnerships. It’s worth considering whether giving $50 million, decades before launch, to a multibillion-dollar mission justifies shutting down a mission as productive as Chandra.

Astronomers have tossed around ideas for other sources of funding for Chandra, such as selling its operations to the Japanese or European space agencies or relying on private donations. Collaboration with other space agencies and companies is standard in astrophysics, but it’s a long process, and much of Chandra’s technology is protected by the US. restrictions on technology transfer. And NASA’s policy directive, while allowing for donations, does not allow for conditions of use. Also, do we want the (sometimes erratic) space billionaires to expand into basic science? Access to the universe is a public good, and most of us astronomers would like to avoid the possibility of oligarchs becoming its gatekeepers.

The tension inherent in Killing Chandra-style astronomical missions stands out. They do amazing discoveriesbut they also have a way of absorbing the budget of medium or existing missions. We the need because more powerful telescopes open up new parameter space, this is the way to make truly revolutionary discoveries. But there is a delicate balance to be struck here: what are we giving up by allocating funding to HWO so early? I would say that we are opening a window, but closing a door. We are choosing to be blind to the high-resolution X-ray universe. And that is a loss for science as a whole.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily their own. American scientific