At the ceremony, families sit on chairs among long rows of small stone graves, marking the thousands of foreign soldiers who fought and died in the Korean War. They are accompanied by serving soldiers from the old regiments of their loved ones.

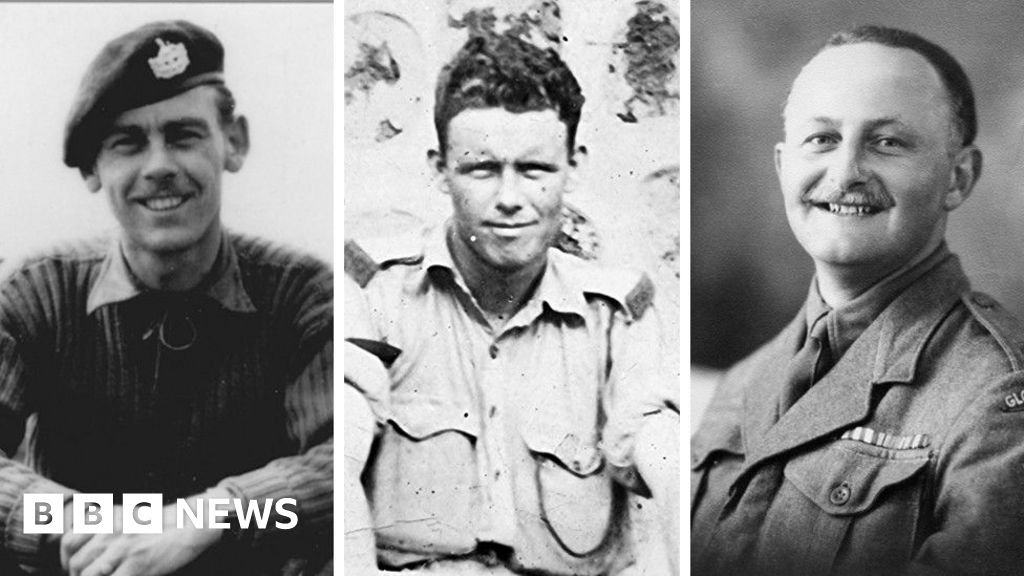

Major Angier’s daughter Tabi, now 77, and his grandson Guy read excerpts of letters he wrote from the front lines. In one of his last addresses, he tells his wife: “Much love to our dear children. Tell them how much Dad misses them and will be back as soon as he finishes work.”

Tabby was three years old when her father went to war, and her memories of him have faded. “I remember someone standing in the room packing canvas bags that must have been his equipment for the trip to Korea, but I can’t see his face,” she says.

At the time of her father’s death, people didn’t like to talk about wars, Tabi says. Instead, the people of her small village in Gloucestershire used to remark, “Oh, those poor children, they’ve lost their father.”

“I used to think that if he got lost, they’d find him,” Tabby says.

But years passed and she found out what happened, Tabby was told that her father’s body would never be found. The last recorded footprint was left under an overturned boat on the battlefield.

Tabby visited this cemetery twice, trying to get as close to her father as she thought possible, not knowing that he had been there the whole time. “I think it’s going to take some time to sink in,” she says from her freshly decorated grave.